When Bethany Saltman’s daughter, Azalea, was born fourteen years ago, she felt love—and impatience and anger and other strong emotions she knew were inside her that we don’t often associate with motherhood.

Saltman, a writer and longtime Zen practitioner who spent several years living at Zen Mountain Monastery in New York State’s Catskill Mountains, decided to investigate these difficult feelings. Her curiosity about the connection between her and Azalea led her to attachment theory and the American-Canadian developmental psychologist Mary Ainsworth (1913–1999). Attachment theory, first developed by the British psychologist John Bowlby and expanded by Ainsworth, posits that our future relationships and many other aspects of our lives are determined by the way that our parents tended to us in our early months, teaching us to regulate our emotions (or not) and to develop qualities such as empathy and insight.

Ainsworth is credited with developing the Strange Situation, a 20-minute laboratory procedure that ascertains the type of attachment shown by a one-year-old baby toward a caregiver (usually, but not always the mother). In the Strange Situation, the child toddles into a room that doesn’t look like a laboratory, making a beeline for the blocks, dolls, or poster on the wall. The parent and child play for a few moments. Then there’s a knock at the door and the parent leaves the child in the room, either alone or with a stranger who has entered and tries to keep the child entertained. Researchers believe that what happens next—tears, ambivalence, anger—determines so much about how we relate to others, not only at a year old, but throughout the rest of our lives.

Ainsworth’s procedure, based on her field research of attachment styles in mothers and their babies in Uganda, was a major development in attachment theory and remains the “gold standard in psych labs everywhere for assessing security between children and their caregivers,” according to Saltman.

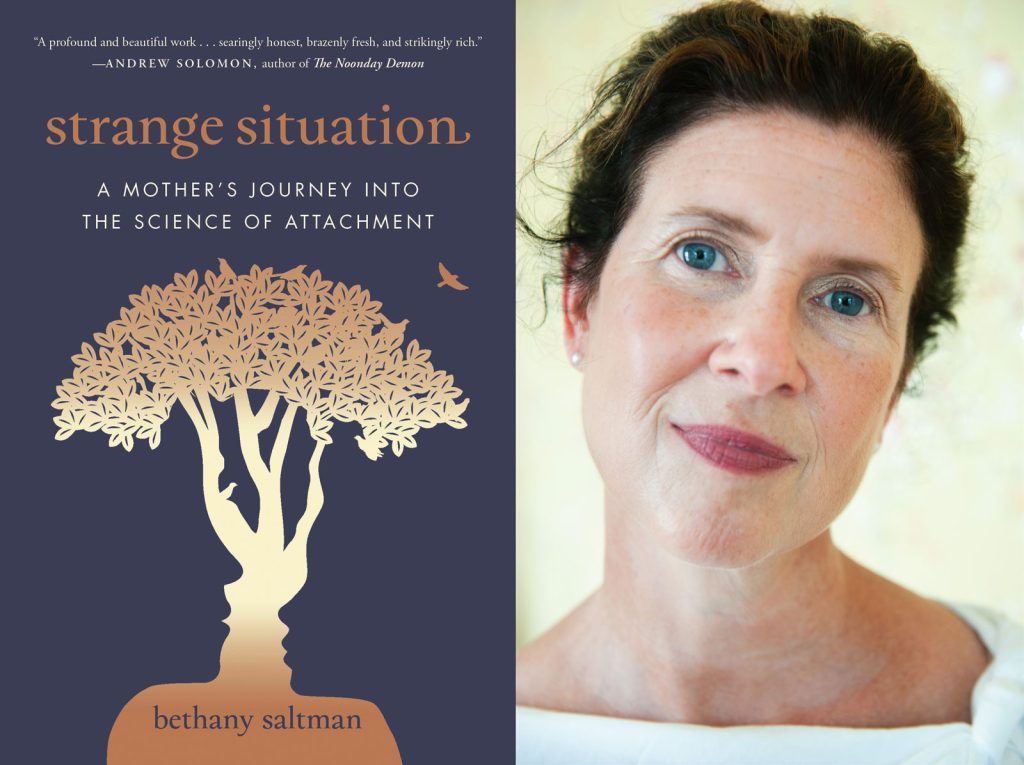

Saltman’s own “discovery” of attachment theory led to more than a decade of research into Ainsworth’s life and work, as well as to an examination of her own relationships and the intersections between attachment and karma. Her book about her findings, Strange Situation: A Mother’s Journey into the Science of Attachment, was published by Ballantine Books in April. Saltman joined Wendy Biddlecombe Agsar, Tricycle’s editor-at-large and resident new mother, to talk about the intersection of dharma and attachment.

***

So, some of my questions are more personal than I’m used to asking. But I have a 10-month-old baby, and it’s hard to ignore that while reading your book. I am totally into that.

I think we have to start with the basics. Can you start by telling me how you became interested in attachment theory? When my daughter, Azalea, was born, I noticed that I was confused by my feelings. In addition to love, I quickly noticed all these other parts of myself appearing—impatience, frustration, anger. I somehow thought that I would enter some other realm and that those edgier parts would be eclipsed by this love. I quickly discovered that this was not the case, and frankly, it scared me. I felt like there must be something wrong with me and I wanted to understand: Am I OK? Can I do this? Can I love this person?

Once a woman becomes a mother, every single thing she does, thinks, and feels is charged because our culture is very invested in the maternal experience.

So I started to read and investigate. I had heard about attachment, but I didn’t understand what it was, and I had become really worried that my so-called “attachment” with Azalea was going to be insecure. Then I heard about the Strange Situation and started to see pictures of Mary Ainsworth, and I just fell for her. I thought: “Who is this woman? She doesn’t have children, she’s very formal, but so friendly.” She’s from an era that I happen to love, and she reminds me of my grandma. And when I realized that in 20 minutes you could learn so much about a relationship between a mother and child I was like “Oh my God, count me in, I want to know everything there is to know about my relationship with my daughter.” For some reason, from the very beginning I really believed in it.

Going back to all of these difficult emotions—we don’t have a lot of examples of the reality of motherhood. I had a baby last year, and I still feel, especially with social media and the way society is, that it’s supposed to be this wonderful and beautiful experience. And when you breastfeed, you’re supposed to have this amazing bond. Sometimes breastfeeding is amazing, but sometimes you’re hungry or tired and you have to pee and you’ve already tried to feed the baby like five times in an hour. And there’s no picture of that. One hundred percent, yes. As I wrote in one article, “People always tell me I’m brave for writing this book.” That comment alone tells me how afraid I should be. But I love my daughter so much, and I am willing to expose myself for her, I can make this an offering and say, “Look, I didn’t just get hungry or have to pee when I was nursing—I got mad.”

But if sitting on the cushion for however many years has taught me anything, it’s that if we can’t open the door to these difficult feelings, they will make themselves known somehow. And it might get ugly. Full stop. If we want to take care of this, there’s one way to do it: be all of our feelings. That’s all there is to it, and it’s very, very difficult.

I gave birth to my son via C-section, and it seemed that everything surrounding that decision seemed to be up for debate as to what was the best thing. I even had one woman in my mother’s group tell me she was so sorry that I didn’t have a “natural” birth. It’s these little things I never realized could be so charged. Well, once a woman becomes a mother, every single thing she does, thinks, and feels is charged because our culture is very invested in the maternal experience. This basically cancels out subtlety, nuance, and real feelings, because they’re very threatening. When, in fact, the bigger threat—as Mary Ainsworth discovered and as the Buddha discovered—is not having those feelings.

I think it’s important to note, like you write in the book, that up until the 1950s researchers believed that babies just needed parents for things like food. You write about the American behavioral psychologist B. F. Skinner, who kept his baby daughter in a climate-controlled “baby box.” The idea that babies need our love and attention was really a radical thing. Indeed. And I think today, as a culture, we are a little bit unclear about where we stand on that. Anybody would say “Of course babies need love.” But what does that mean for us? We almost treat the idea of needing love with a behaviorist slant—like love is a thing that you present with your breasts. It’s this belief that our children need us, because we don’t like love that’s messy. It’s the Instagram version of love, which is an awful lot like a baby box.

So you mean that love in our culture could mean doing something for your baby, like feeding them organic food, more than the actual feeling? That’s the checklist approach to love and attachment. This idea of doing things right is rigid and so deeply entrenched in our minds. It’s easy to say “Of course I love my baby, and of course they need me to love them. Look, I’m nursing, I’m feeding them organic stuff. I’m driving myself insane with effort, that must mean something. I’m smiling, I’m rejoicing, I’m doing all these things.”

But what Mary Ainsworth noticed in securely attached relationships was “mutual delight.” That is something that you can’t fake. We’re getting really good at almost faking it with our phones and pictures. We can look at someone’s Instagram feed and think they’re delighting in life. But we must know better, right?

How exactly do researchers determine attachment patterns based on 20 minutes of watching a child and mother in a room? During the Strange Situation, the researchers observe and take very particular notes about what’s going on during these reunions and separations—all the different types of attachment behavior. Ainsworth had a system of determining what kind of attachment relationship was being expressed during the 20 minutes, and they all flow from three types of behavior: secure, insecure/avoidant, and insecure/resistant [a fourth classification was later added for babies that were inconsistent, disorganized, or confused]. There are also subsets of these primary classifications.

The Strange Situation is not an experiment; it’s a research tool. You get a baseline of the kind of relationship this parent and child have, and use that information for some kind of strategic solution—group therapy or video-based interventions, for example—that promotes reflective, functioning parents. You might use the Strange Situation at the end of the strategy to see whether it worked.

Researchers have also found that there’s a 75 percent correlation between a parent’s attachment and their child’s attachment at one year. Can you explain how the Strange Situation is used to come to that conclusion? In terms of our future this is a really important point, and one that dharma practitioners will be able to appreciate. What we see at one year is a flash, a snapshot of where that relationship between a caregiver and child stands, based on millions and trillions of minute interactions that have happened in that first year. Non-Buddhists often think of karma as some moral law or destination, as in you get what you deserve. Sometimes we do, and sometimes we don’t. What the Buddha meant by karma is the way every cause will have an effect. We can’t always know what that effect will be, but an accumulation of karmic seeds will affect us, for sure. This is true in culture, as we’re seeing now more clearly than ever, and in our families.

Karma works by developing power as it continues, and the only way to stop a karmic causation is to get in its way and give it a stronger dose of something else. Otherwise, our attachment tends to continue, not because there’s something magical about being one year old—it’s just karma; it’s just the way it goes. It’s incredible the way karmic seeds are sown and harvested. A strong positive event can certainly shift things. But if you’re avoidant at a year, you’ve got a good chance of being avoidant at 30.

I’ve felt a wide range of emotions since learning about this. It’s so amazing! But it’s also scary. What if I’m not securely attached, and then my son isn’t, either? There’s this opportunity and hope for change, and then this idea that things are just the way they are, that there’s no beginning and no end. Where do we go from there, in our practice, in our families? We practice. That’s all there is to do. It’s interesting information, but it doesn’t change the reality, which is that we’ve got one heart, one life to live.

I think the path of practice is the clearest thing in all of this. Everything else depends on so many different causes and conditions, but the path out seems to be clear. That’s what a securely attached adult does: they have mixed feelings. The avoidant baby at one year old is denying. It’s like that very fundamental dharmic understanding of heaven, hell, and other realms, jealous gods and all of that. Clinging takes many forms and so the avoidant baby is clinging to denial, to not feel what they’re feeling, by a year.

Well, and then there’s the other side, the resistant baby is also clinging to an idea of I’ll get it at some point, at some point this is going to feel good. Whereas the securely attached baby is able to actually experience their emotions to the point of extinguishing them, with the help of the parent. By the time we’re sitting on our cushions, we’re trying to learn how to do that on our own, extinguish our sensations by practicing them. By seeing through them, by experiencing them. A baby cannot do that, so that’s where we come in.

The avoidant baby in the Strange Situation is chilling. Their heart rate and stress levels are going up, but they sit there like a stone, while their parent is in the doorway, saying, “Daniel, I’m here, hi.” The avoidant babies ignore their own experience; they can’t tolerate the feeling of sadness, and by a year they’re repressing, they’re angry, they’re distancing themselves. They’re separating from their own experience because the parents, for whatever reason—and there are lots of good, understandable reasons—haven’t been able to be present with their child enough so that the child has fluency with their own sensations. And then the resistant child: they can feel for a second, then they have to step off, and then feel again, then step off.

What are some good reasons why a parent may not be able to be present with their child? They’re depressed, or had a traumatic childhood and never learned how to be attentive. Or they’re experiencing COVID-19, poverty, job loss. There are innumerable good reasons. A parent might have a hard time paying attention to a child because they’re having a hard time with their own experience and their internal life. And for those reasons, the result might be the same: a child won’t feel like they can trust that the parent will be there for them, which might lead to avoidance behavior at one year old.

One of my favorite concepts to come from the attachment literature was from Mary Main, a psychologist who had studied with Mary Ainsworth: she called it attentional flexibility. From a dharma perspective, that’s golden. When we’re sitting on our cushion and have thoughts passing through, our intention is to let go of them and return to the present. That’s developing attentional flexibility, and a secure baby in the Strange Situation has this. They are despairing, at the brink of death, their loved one is gone, and that is a seriously distressful situation. So they’re brought to the edge just a little bit and then when the parent returns they’re able to be, like, “Oh . . . that’s over,” and go back to playing. It’s like when we notice we’re thinking when we’re sitting. It takes so many of us a lifetime—at least—to learn how to do this, because we don’t have intentional flexibility—we get so stuck in our thoughts or lost in space. We’re rigid, we’re excessive, we’re avoidant, we’ll do anything but be present in the moment. And we can see that happening exactly in the Strange Situation with an insecure one-year-old. The insecure baby gets caught in their feelings of loss when the parent leaves, and they can’t return to playing when the parent returns because they don’t have a trusting relationship.

I’m definitely curious, and I’m sure other people will be, too. Do you have advice for people who want to learn more about their first year of life? Can this knowledge help us? As interesting as our patterns are, ultimately, I don’t think we have to know all the details of our early lives. If you’re really interested, then practice becoming more present. You’ll learn everything you need to know through rigorous self-study. By learning to work with yourself, you’ll become a more delighting person and parent, and your child will become more securely attached and just a happier person. It’s not like if you’re avoidant there’s one treatment and if you’re resistant there’s another.

Get right with yourself, get to know yourself, metabolize your feelings, and ask what is getting in your way. I could go on and on, but that’s our work as dharma practitioners and the work of anybody who wants to free themselves of their past. The past is fascinating and I totally support therapy and any kind of work you want to do. But ultimately, everything we need is right here, right now, in the present, on the cushion or wherever you are.

What haven’t I asked you that you’d like people to know about the book? This book is not just for parents; it’s for anybody who has a parent. Because it isn’t just about how we raise children—it’s how we raise ourselves to be reasonable, happy, delightful adults. And it’s never too late, or too early, to take a look at our minds. To me, a secure attachment is kind of a North Star: Some of us may never get there, but that doesn’t matter—it matters that we have intention and that we manifest that lovingkindness from wherever we begin.

Your book reminded me about something that Sharon Salzberg talks about in a podcast I listened to recently. She had a very difficult childhood, but she says that she was able to “re-parent” herself through her teachers by drawing upon qualities she saw in them. Exactly: the way that we talk is important, and we talk to our children the way we talk to ourselves. A friend of mine recently said, “The first person you talk to in the morning is you.” If we can put a microphone to that voice and hear it, we would learn a lot. And you don’t have to be a meditator, or a Buddhist—we’re just in a very fortunate position because we have the tools.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.