The graduate students and faculty in the program of computer graphics at Cornell University are slowly but surely developing the means to generate photographically real images of architectural spaces that don’t exist. “We write software that can function the way a camera does,” explains senior research staff member James Ferwerda. “Our aim is to show exactly how a building would look if it were built.”

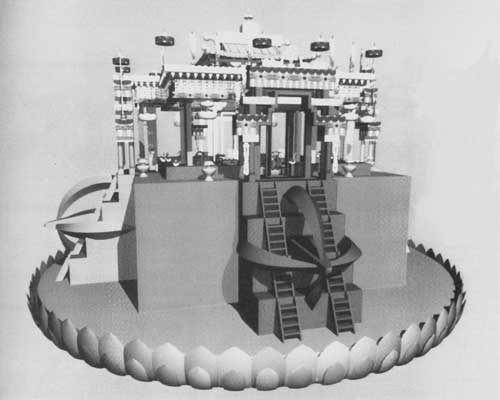

The computer graphics team likes to tackle difficult projects so they can expand the imaging capacity of their software. That’s why, several years ago, they agreed to help the Tibetan Buddhist monk Pema Chogyen create a detailed computer model of a three-dimensional mandala. Like other three-dimensional mandalas, the thirteen-deity Vajra Bhairava mandala represents the perfected world of the buddhas. It is an intricate architectural form that centers around a square palace, the home of the thirteen deities. All 3-D mandalas are interlocking symbol systems that are built up detail by detail in the minds of Tibetan Buddhist meditators in the course of their practice; each element is important because it represents a different aspect of Buddhist thought.

Learning to visualize a 3-D mandala is a difficult task, and knowledgeable teachers are scarce in this country, which is what motivated Pema Chogyen to spend two years at Cornell helping to design this extraordinary visual aid. Chogyen’s creation, now available as a home video entitled “Exploring the Mandala,” features a three-dimensional space that blooms from a two-dimensional sand mandala like a flower in a time-lapse film. “What we’ve achieved, really, is that just by spending seven minutes in front of a screen, you can get an idea what a mandala looks like,” says the thirty-six-year-old monk, who is also a graduate student Columbia University.

Chogyen adds that the way the mandala unfolds in the computer-generated model is not the way a real visualization unfolds. His intent was to show graphically the relationship between a two-dimensional mandala, which is really a blueprint, and a three-dimensional mandala. The real mandala, the real aim of visualization practice, stresses Chogyen, is to behold and contemplate “an enlightened environment, an enlightened world in which everything is in balance.”

The aim of the young computer scientists was to make the mandala as physically real as the state-of-the-art software would allow. “The key word is ‘physically-based'” says Ferwerda, who explains that they can make imaginary structures look like photographs by “simulating the way light would reflect and refract and be transferred by the various materials that would go into a building.”

The palace of the thirteen deities was created exactly the same way the graphics team builds other structures. “We make a geometric model,” says Ferwerda. “Then we study the materials that would go into the building, exactly the way physicists and chemists would analyze them, and that’s how we make an image.” Although it is far from realistic in every detail (the five diamond buddhas are represented by syllables), it sprouts some breathtaking details: a cornice of intricately sculpted gold glints as though struck by the sun; jewels glow; ornate silken banners hang heavy around the crown of the palace.

Ferwerda claims that although the mandala referred to unfamiliar concepts, the members of the graphics team could relate to it. “The parallel that I find interesting in this project is between the kinds of scientific visualization that we do and the kinds of visualization that are done within the practice of Tibetan Buddhism. There are many similarities in the sense of trying to make complex phenomena or relationships visible.”

“Exploring the Mandala” awed people when it was screened at an exhibit of Tibetan Buddhist art several years ago. Still, Chogyen expects some negative reactions to the new imaging technology. Human nature being what it is, he concedes that imaging may be feared the way some traditional people fear cameras—as a kind of demonic force that can suck the secrets and the life out of the image, leaving nothing but bones or, in this case, a zippy Disney version of the dharma. Some Buddhists, he allows, may even dismiss this project as a superficial kind of East-West promotional video calculated to show the Western world how open-minded and scientific Tibetan Buddhism is. “It’s a visual aid,” explains Chogyen, who stresses that the Dalai Lama blessed the project from the start. “We decided not to have narration partly because in the tantric teachings the meanings are secret, and real students know there are texts and teachers that they can go to for that.”

To fear or dismiss this new model on the grounds that computers are inescapably dualistic, insists Chogyen, is to miss how accurate it really is. In some details this digital mandala is much more accurate than any of the old Tibetan three-dimensional models that were made of copper, gold, wood, or other materials. “The computer can show floating things, for example,” says Chogyen. “Old models tried to use strings for that. And the computer can show the transparency of the five different color worlds.”

Indeed, the project was conceived to help clear up Western misunderstandings about the mandala. Sidney Piburn, a senior editor at Snow Lion Publications, explains that Chogyen was brought to the United States to work on what was intended to be a book about the mandala because he was the best artist at the Namgyal monastery in Dharamsala, India. Chogyen moved to an affiliated monastery in Ithaca, New York, where Snow Lion Publications is located, and set to work with Piburn.

“Pema decided he wanted to illustrate a book in the Western style because it was to be a book for Westerners,” says Piburn, who knew about the computer graphics program at Cornell and took Perna there. “I thought they might have suggestions about drafting software Perna could use for the book.” Instead, the director of the program was so taken by Chogyen’s project that he provided the monk with an office; there, Chogyen drew Western-style pictures, which were translated into the software that ultimately became “Encountering the Mandala.”

Chogyen hopes that this first effort will inspire further projects. And it’s bound to happen: the program in computer graphics at Cornell has established a scholarship for Tibetans. “It will go on, and I think it should go on,” Pema continues. “For a long time, computers have been used to explore the outer world, but they may be able to be changed or transformed to help us explore the inner world.”

Note: “Exploring the Mandala” is available from Snow Lion Publications.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.