As the wife of a prominent Chicago attorney she had had a great deal of experience at entertaining,” wrote Mary Farkas in a 1967 obituary of Ruth Fuller Sasaki that appeared in the monthly newsletter Zen Notes. Sasaki, who during her first marriage to a corporate lawyer had been Ruth Fullcr Everett, had joined the Buddhist Society of America in 1938 on the same night as her friend Mary Farkas. In the obituary, Farkas seemed to speak with genuine admiration of this early incarnation of Mrs. Sasaki and of virtues that sound quaint today but were not in the 1920s, when Everett was a young woman. “There was no dish she wouldn’t try to make, no problem of gardening, decorating, or construction she wouldn’t undertake to solve,” wrote Farkas. “Servants in her employ left trained professionals.” You’d have thought Farkas had been speaking of Mrs. Sasaki’s finest achievements.

Actually, she was speaking of a woman who in 1956 was the first foreigner to be ordained as a Zen priest in Japan, and who, by the time of her death in 1967, had overseen important translations of classic Zen texts.

Mrs. Everett took an early interest in Buddhism. In her twenties she read everything she could find about the Theravada tradition; there was virtually nothing available at that time in English about Zen. She apparently first learned about Zen from a man named Pierre Bernard, who had an ashram in Nyack, New York, where he taught hatha yoga and “tantra.” But it was only on a world tour in 1930 that Mrs. Everett stopped in Japan and met D.T. Suzuki, the man largely responsible for introducing Zen to the West. He gave her a book of his essays, and she asked him for meditation instruction, which she had apparently been unable to find anywhere else. She wanted to see, she said, if the practice could be of any value to a foreigner.

In 1932 she returned to Japan, and with a female boldness that must have been startling—but which somehow doesn’t sound surprising for a society matron from Chicago—asked to study with the Zen master Nanshinken Roshi, who had a reputation as one of the severest Rinzai masters and did not permit women in his zendo.

Mrs. Everett was kneeling in wait for her first interview with Nanshinken Roshi when she noticed a large Morris chair in the far corner of the reception room. “Upholstered in bright green velour,” she later said, “its red mahogany arms were dotted with pearl buttons which if pushed…sent the back down with horrifying speed, and caused arm and footrests to spring out suddenly from least expected places.” Nanshinken Roshi apparently believed American women incapable of sitting in cross-legged posture and told her she could sit in this chair in his house, because her apartment would be too noisy. He told her he wished she could occupy the zendo, but the monks would not have the chair. Tactfully, Everett seems not to have questioned these restrictions at first, bur within three weeks the chair was gone and she was sitting in the zendo where, for the first time, she felt she had finally come home. She was forty years old.

Mrs. Everett remained in Japan for three and a half months, even completing an extremely difficult week of rohatsu-sesshin, when the monks sit practically round the clock. It must have been difficult for her to return to the West, where she would find little support for what she was doing and would be unable to practice with the same intensity. It was after a subsequent trip to Japan that she stopped in London and met the young Alan Watts, on whom she would have a considerable influence, and who was immediately smitten with her daughter Eleanor. When Everett returned to the United States, where she and her husband had relocated to New York, she met the teacher who would have the most profound influence on her life: Sokei-an Sasaki.

Sokei-an had first come to the United States in 1906 with Sokatsu Shaku, a Zen master who, like his more famous teacher, Soyen Shaku, was determined to bring Zen to America. Sokei-an was at that time a twenty-four-year-old art student, trained as a wood-carver, who at the age of fifteen had taken a walking tour of Japanese temples to carve dragons for them. “Carve me a Buddha,” Sokatsu Shaku had said to the young man when they met. But when Sokei-an returned two weeks later with a small statue he said, “What is this?” and threw it out the window. He had meant for the young man to carve out the Buddha in himself.

Before Sokatsu Shaku and his delegation left Japan in 1906, Sokei-an married a woman in the group named Tomeko, because it was considered improper for a Japanese woman to travel without family. Sokatsu Shaku led the group to California, where they tried to start a farm but, inept, were mocked by the local farmers. Sokei-an studied at the California Institute of Art in San Francisco, and when Sokatsu Shaku returned to Japan, he and Tomeko stayed behind. After the two of them had been living in Seattle for a while, Sokei-an walked over the mountains into Oregon, where he found work on a farm and Tomeko joined him. They had two children and she was pregnant with a third when she decided to return to Japan.

Sokei-an soon made his way to New York, where he grew his hair and led a bohemian life in Greenwich Village. He met the occultist Aleister Crowley and, with Maxwell Bodenheim, translated some poems by Li Po for The Little Review. He also wrote sketches for a Japanese newspaper and supported himself by working in art stores. But while walking the streets one day he saw the carcass of a dead horse, and with that reminder of mortality, wished to see Sokatsu Shaku again. For a few years he shuttled back and forth between the United States and Japan, supporting himself as an art restorer and wood-carver. On one crossing he suddenly threw his chisel overboard and resolved to complete his Zen study, which he finally did at the age of forty-eight. “Your message is for America,” his teacher told him. “Return there.”

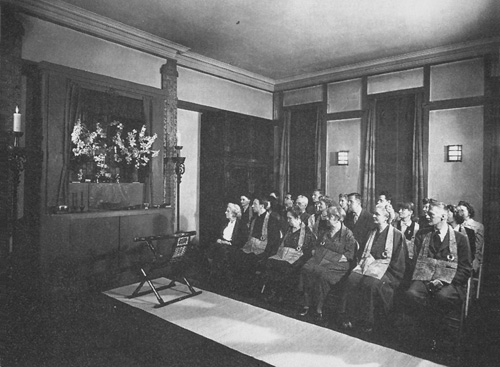

Sokatsu Shaku believed in a lay tradition and wanted Sokei-an to return as a lay teacher, but Sokei-an, who didn’t believe he would have sufficient authority, got another teacher to ordain him as a priest. Sokatsu Shaku, who was furious, never spoke to him again. Sokei-an returned to New York but didn’t know how to proceed. At one time he tried to talk to people in his apartment building about Zen, but they were so offended he eventually had to move. Finally, he met a businessman named Mr. Mia, who gave him five hundred dollars and found him a place to live. In a one-room apartment at 63 West 70th Street, which also served as his residence, Sokei-an founded the Buddhist Society of America in 1930. “I had a house and one chair,” Sokei-an said. “And I had an altar and a pebble stone. I just came in here and took off my hat and sat down in the chair and began to speak Buddhism.” By 1938, when Mrs. Everett joined the society and was given the name Eryu (“Dragon Wisdom”), there were thirty members.

Sokei-an seems to have had some trepidation about asking Westerners to sit cross-legged, and when Mrs. Everett joined the group they were sitting in chairs for thirty minutes of meditation, after which some of them met with him for koan study and he gave a lecture. Mrs. Everett immediately insisted on cross-legged sitting, at least for the younger members, and instituted a regular session of zazen at 8:00 A.M. She eventually moved the organization to two floors of a brownstone she had bought on East 65th Street, and in time the name was changed to The First Zen Institute of America.

Despite these halting and modest beginnings, however, Sokei-an seems to have been a remarkable teacher who taught with more than his words. “It was, of course, his silence that brought us into it with him. It was as if, by creating a vacuum, he drew all into the One after him,” wrote Mary Farkas. He taught in the tradition of Hakuin, the great eighteenth-century Zen master of the Rinzai school, who formulated a succession of koans requiring specific answers. It was a style that had proven too constricting for the young Alan Watts, who by that time had married Eleanor and moved to the United States. Though his books introduced Zen practice to countless Americans, he himself would never become immersed in the practice. Nevertheless, Sokei-an was an important influence on him. “He never fidgeted nor showed the nervous politeness of ordinary Japanese,” Watts said, “but moved slowly and easily, with relaxed but complete attention to whatever was going on.” According to Watts, Sokei-an once said that if he “had any ideal at all it was just to be a complete human being.”

Mrs. Everett’s husband Charles had been seriously ill since 1936, and finally died in 1940. Sources are all discreetly vague about the timing of what happened between her and Sokei-an, but at some point, at least according to Watts, they fell in love. They had begun translating the Sutra of Perfect Awakening, and Everett was bringing her thoroughness and perfectionism to the new area of scholarship. According to Watts, he and his young wife “were the fascinated witnesses of [Sokeian and Mrs. Everett’s] mutually fructifying relationship—she drawing out his bottomless knowledge of Buddhism, and he breaking down her rigidities with ribald tales that made her blush and giggle.”

Pearl Harbor was bombed on December 7, 1941. The Buddhist Society—as it was then still known—was put under surveillance, and both Sokei-an and Mrs. Sasaki were questioned by the FBI. In July of 1942 Sokei-an was moved to an internment camp, where he occupied himself by carving a walking stick with a dragon emblem; he would later remind his students it was by fighting that people got to know each other. Mrs. Everett hired a lawyer to obtain his release, but he had been ill when he entered the camp, and his stay there didn’t help. By the time he had obtained a divorce from Tomeko and married Mrs. Everett in 1944, his condition was grave. “I have always taken nature’s orders,” he said, “and I take them now.” He died on May 17, 1945.

Sokei-an had left his wife with two deathbed wishes: to find another Japanese teacher for the Institute, and to finish his translation of the Recorded Sayings of Rinzai. As soon as she was able after the war, she returned to Japan and settled in a house near the Kyoto zendo of Zuigan Goto Roshi, who had also been a student of Sokatsu Shaku and had been a part of the 1906 delegation to New York.

Sokei-an’s wishes proved more complicated than they might have seemed. It wasn’t just any Zen teacher who wanted to move to the United States, particularly right after World War II. The First Zen Institute continued to meet, with readings from Sokei-an’s talks, but though Mrs. Sasaki had been hopeful at first, by 1952 she was telling the group they were on their own. For a time Isshu Miura Roshi—who had been the head monk at Mrs. Sasaki’s first zendo in 1930—visited New York, so the group had a chance to do koan study. He gave a series of lectures, published in 1966 with an introduction by Mrs. Sasaki as Zen Dust, but decided not to take over the Institute.

The task of translation also proved to be daunting. The Rinzai records included koans that were in ancient and colloquial Chinese, difficult even for an expert to translate, so the task of language study was enormous, and Mrs. Sasaki probably never acquired the expertise she needed. Instead, with characteristic thoroughness, she assembled a distinguished team of translators, including professors Philip Yampolsky and Burton Watson, both from Columbia University, and the poet Gary Snyder, whose real wish was to study Zen, but whom Mrs. Sasaki brought to Japan to work on the translation team. Even a team of experts, however, was not enough, as Goto Roshi informed her of a tradition that no one should translate a koan who had not solved it. She therefore had years of koan study to do as well.

Goto Roshi actually wanted Mrs. Sasaki to be a missionary, to return to the United States to teach, but she was perhaps constitutionally more a scholar than a teacher, and was determined to complete the task her husband had set her. Goto Roshi expected his wishes to be followed, and was angry when they weren’t, but it seems that Mrs. Sasaki felt a greater loyalty to her husband, who after all had been her teacher first. For five years she didn’t visit Goto Roshi for koan study, though she continued to sit zazen and send him gifts on holidays. One year he answered with a thank-you note, and his anger seemed to have disappeared.

In 1956, when Mrs. Sasaki was occupying a small temple on the grounds of Daitoku-ji, the main temple complex of the Rinzai school, and overseeing her team of scholars, she got permission to build a library and a sixteen-seat zendo. If she couldn’t find a Japanese teacher to come to the United States, she would at least have a place for Americans to stay in Japan while they practiced Zen and did language study. In effect, she had created a temple, which needed a priest, and she herself was ordained and named to the post. She called her new complex The First Zen Institute of America in Japan.

Mrs. Sasaki never did find a teacher to take over the Institute in New York, though Mary Farkas had long since assumed the task of overseeing it, and Sasaki’s work on Rinzai was not quite finished when she died in 1967, a few days short of her seventy-fifth birthday. Seen in one way, she hadn’t accomplished either of Sokei-an’s requests. Yet in a larger context, their whole story was remarkable: a young art student who wandered for years before he finally realized he was a teacher, who opened his institute with eight students in a one-room apartment; and the society woman who led an apparently successful life in Chicago with a gnawing sense that something was missing, and who had to discover a large drafty hall in Japan before she felt she was where she belonged—a woman whose circumstances enabled her teacher to reach a far greater audience than he otherwise would have. The starry-eyed and somewhat stilted speaker who gave her first talk in a Japanese zendo in 1934 had, by 1967, become a substantial scholar, one who spoke with real authority.

For years Mary Farkas published Sokei-an’s teachings in Zen Notes, as well as the “Letters from Kyoto” that Sasaki would send to The First Zen Institute community. The Record of Lin Chi—the translation of Rinzai from the Chinese over which Mrs. Sasaki had labored for so long—was published in Japan in 1975, and a book of Sokei-an’s teachings,The Zen Eye, was published in 1993. Other books of his lectures—on Rinzai and on the Sixth Patriarch—are still in preparation. Since Mary Farkas’ death in 1992, Robert Lopez has continued to publish Zen Notes, and The First Zen Institute, now located on East 30th Street in Manhattan, continues to thrive.

But perhaps it is short-sighted in the field of Zen to speak of the accomplishments of these two at all. Sokei-an would have been as great a teacher had he taught only those first eight students—great teachers have had fewer. And, in the end, the most remarkable thing about Mrs. Sasaki was just the life she led, and the courage she showed in carving a Buddha out of herself.

Letter from Japan

The following is excerpted from a letter to members of The First Zen Institute of New York, published in Zen Notes, Volume V, Number 7.

The appointment of myself, an American, as the priest of a Rinzai Zen temple is unique in the history of that sect. The fact that I am a woman is not of such importance, for there have always been, at least in Japan, some Zen temples presided over by nuns, to which category, of course, I now belong. The formal dedication of the Zendo at Ryosenan, a building to be devoted to the purpose of the work of our Institute, that is, of making traditional Zen study available to western students, brought in another unusual element. Moreover, our Kyoto branch, now formally called The First Zen Institute of America in japan, is the first organization ever to be formed for that purpose in China or Japan, as our American Institute was the first in the West.

To Sokei-an Sasaki Roshi, founder of our American Institute, must be attributed the initial impetus to these events. Sokei-an was a priest of Daitoku-ji and, strangely enough and unknown to us all until just recently, a member of the Ryosen-an Line of priests within Daitoku-ji. The mother temple of this line had been the old Ryosen-an, of the founding and demolishing of which I have already written you, and on the former land of which was situated the house I came to live in in Daitoku-ji. Such relationship or innen, as it is called in Japanese Buddhism, is much respected and cherished here. It has contributed greatly to the closeness of the bond that Daitoku-ji feels with all of us in the Institute, and to their wish to aid us in the future in whatever way they can in furthering the spread of traditional Zen teaching to the West.

The first step in all these proceedings was the invitation from Daitoku-ji Honzan (Administrative Headquarters) to our Kyoto Branch to make the Building we have erected on a part of the old Ryosen-an land into a sub-tempIe to be known as “The Restored Ryosen-an.” The rather tedious process followed of registering the new temple with the prefectural government. The laws of Japan regarding the establishment of religious organizations are much more complicated than those of New York State, for instance, and several months were needed for the preparation of the many, many documents with their countless official seals.

The second step was that of my taking tokudo. The word literally means “to pass over” from the family life in the religious life. At this time the postulant takes the monks’ vows from his teacher and usually his head is shaved. No, do not fear. My hair has not been cut off, nor will it be. There are rules for exceptional cases, and mine was considered to be one. Oda Sesso, the Kancho of Daitoku-ji, gave me the vows. To enter the Daitoku-ji priesthood one must have an active member of the Daitoku-ji priesthood as one’s teacher. My Zen Master, Goto Roshi, though a past Kancho of Daitoku-ji, is now living in retirement, so the position of my “commandment teacher” was taken by the present Kancho, who is Goto Roshi’s Dharma-heir.

In the course of the very simple ceremony I was taken to the hondo—”main hall”—of the monastery, where the Kancho lives since he is Roshi as well, and allowed to bow and burn incense before the figure of Daito Kokushi, founder of the line of Daitoku-ji teaching, which you may remember the Kokushi brought directly from China when he returned to Japan in 1269 as the Dharma-heir of Kido Osho of Kinzan. This life-sized figure carved of wood has been placed deep within the main shrine of the hondo. The Kokushi sits, as he must often have sat in life, full of power, his eyes—of glass—glaring in the light of the candles, his real stick uplifted ready to strike. It is quite an experience to walk into that shadowy place and stand face to face with the old man.

The next step was to confer with the Chief Secretary of the Honzan about the ceremonies themselves. Tokuzen San was a marvel of efficiency and of kindness as well. The guest list, the gifts to be given, the food, what I was to wear, each detail of the ceremonies themselves—who came first, who came second, where each one walked, where they stood, what sutras were to be chanted, when and how and who was to bow—all this was written down in the Secretary’s handsome calligraphy, making a veritable book for my guidance. My constant personal mentor through the maze was Kobori Sohaku, a younger Daitoku-ji priest, though not yet with his own temple, as he is still engaged in koan study. Kobori San speaks excellent English, and often through those weeks I thought with gratitude of the late Beatrice Lane Suzuki, Dr. Suzuki’s wife, who had taught Kobori San English so thoroughly….

Alone at the altar of the Founder of Daitoku-ji, I bowed three times, forehead on the ground, then entered into the deep recess of the altar, where only disciples in Daito Kokushi’s line may enter, and, as previously at the monastery, bowed again and burned incense before the life-sized figure seated in its depths.

—Ruth Fuller Sasaki

Ryosen-an temple, Daitoku-ji, June 3, 1958

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.