For centuries, people around the world have reported experiences of lucid dreams, in which they know that they are dreaming while they are in the dream state. But as recently as thirty years ago—a hundred years after the scientific study of the mind began—no scientific evidence existed that anyone could be conscious while dreaming, and most psychologists were still convinced that lucid dreams were impossible. There were philosophical reasons for such skepticism as well: after all, how could anyone be awake and asleep at the same time?

It just didn’t make any sense, especially to those who never had a lucid dream and couldn’t imagine anyone else having one.

Author and psychophysiologist Stephen LaBerge was one of many people who had occasionally experienced lucid dreams since childhood, and as a young man it occurred to him that this would be a fascinating area of research. In 1977, he began his graduate studies in this new field at Stanford University, gradually developing methods for inducing lucid dreams and recording his own personal experiences, resulting in nearly nine hundred lucid dream reports over the next seven years. But how to persuade his scientific colleagues that we really can become awake in our dreams?

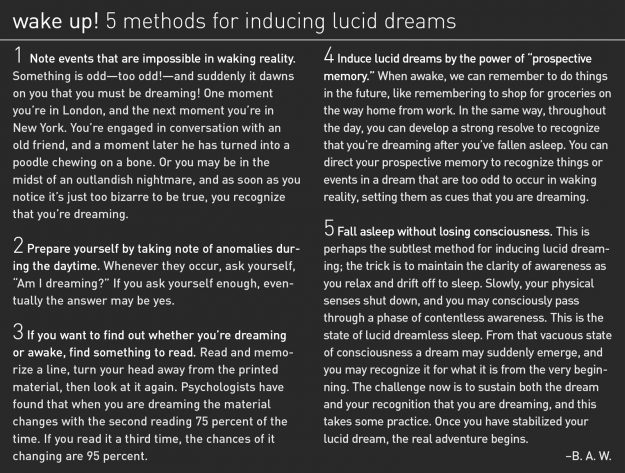

The challenge, he recognized, was to communicate from a lucid dream to people in the waking state. One obstacle was that during sleep, most of the dreamer’s body is paralyzed, but psychologists had already discovered that the eyes move while dreaming and that the eye movements of a sleeping person correspond to the eye movements of the person within a dream. In one famous study done by Stanford University sleep researcher William C. Dement, a dreamer was awakened after making a series of about two dozen regular horizontal eye movements. When asked what he was dreaming about at that time, he replied that he had been watching a long volley in a ping-pong game! This gave LaBerge an idea. If he could become lucid in a dream, while his scientific colleagues were monitoring his brain states and rapid eye movements to ensure that he was indeed dreaming, he could then send signals to them by moving his dream eyes in a prearranged way. Since his physical eyes would track in the same way as his dream eyes, he could provide objective evidence that he knew that he was dreaming. Ultimately, LaBerge was successful in providing such empirical proof of lucid dreaming. His work and other related studies have now been widely accepted within the Western scientific community, and scientific researchers in the field of lucid dreaming have devised a number of ingenious methods for helping ordinary people awaken to their dreams. [See “Wake Up! 5 Methods for Inducing Lucid Dreams” at end of article]

An astonishing range of possibilities is open to the lucid dreamer who is interested in exploring the nature of the mind. You may use lucid dreams simply for recreational purposes, with the range of possible events in the dream limited only by your imagination. Then, as you venture into more meaningful activities, you may learn to solve psychological problems in the dream or to explore the malleability of the dream by changing its contents at will. Or maybe you’ll choose to tap into the depths of your own intuitive wisdom. You may, for example, invoke your own archetype of wisdom—a Greek philosopher, a goddess of wisdom, or any figure that represents your ideal of sagacity. As you converse with that person in your dream, you are not accessing any outside source of knowledge but unearthing hidden resources within your subconscious to which you don’t normally have access.

______________

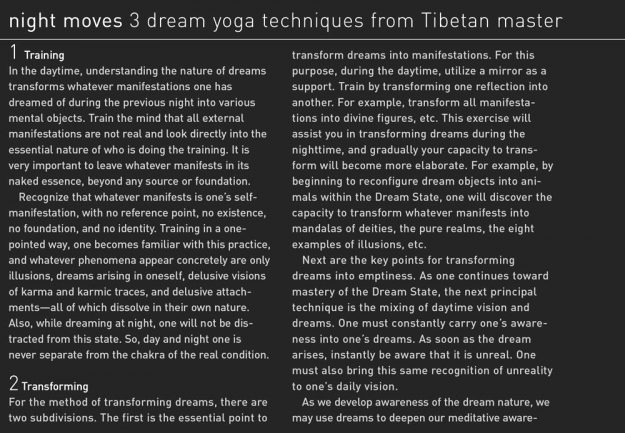

Beyond these explorations of the mind, lucid dreaming provides an ideal forum for examining the essential nature of dreams and reality and the relationship between the dreaming and waking states. Accord- ing to recent scientific research, the principal difference between dreaming and imagination on the one hand, and waking perception on the other, is that waking experiences are directly aroused by stimuli from the external world, whereas imagination and dreaming are free creations, unconstrained by physical influences from the environment. According to Buddhist thought, however, Western science tells only half of the story. Buddhism and science both agree that although sights, sounds, and tactile sensations of the world around us seem to exist out there, they have no existence apart from our perceptual awareness of them. But Buddhism adds that mass, energy, space, and time as they are conceived by the human mind also have no existence apart from our conceptual awareness of them—no more than our dreams at night. All appearances exist only relative to the mind that experiences them, and all mental states arise relative to experienced phenomena. We are living in a participatory universe, with no absolute subjects or objects. With this primary emphasis on the illusory nature of both waking reality and dreams, Tibetan Buddhists formulated a system of teachings known as dream yoga over one thousand years ago that uses the power of lucid dreaming to break down our illusions and unlock the door to enlightenment. [See “Night Moves” at end of article]

In dream yoga, once you learn to recognize the dream state for what it is through lucid dreaming, you can begin to explore the nature of the psyche—your own conscious mind within this lifetime. At a more fundamental level, you investigate the nature of the substrate consciousness (alayavijnana), the individual continuum of consciousness out of which the psyche develops during gestation in the womb and into which it dissolves at death. In the highest stage of dream yoga, the ultimate, “clear light” nature of consciousness, or pristine awareness (rigpa), is revealed, the realization of which is central to the Tibetan teaching known as the Great Perfection (Dzogchen). Each stage of dream yoga practice leads to ever-deepening self- knowledge, finally resulting in Buddhahood itself. The Great Perfection teachings declare that the only difference between buddhas and ordinary sentient beings is that the former know who they are, while the latter do not.

The daytime practice of dream yoga centers on maintaining the awareness that everything we experience around us is illusory. Although things appear to be out there, independent of any perceiving or conceiving subject, everything is “empty” of such an inherent self-nature. Descartes’s absolute split between subject and object, which has exerted an enormous and lingering effect on Western science, is totally rejected in Tibetan Buddhism. All things, mental and physical, consist of dependently related events, with no absolute demarcations between subject and object, mind and matter, or outer and inner. The nighttime practice of dream yoga begins with recognizing that you are dreaming and then sustaining that awareness. To achieve such attentional stability and clarity, it’s very helpful to train first in the practice of samadhi, or focused attention, both during the daytime and as you fall asleep. Once you’ve stabilized your awareness that you are dreaming, you progress to the second phase, in which you learn to control and transform the contents of your dreams. This is not just an ego trip, seeing how much you can dominate your dreams. Rather, it is a practical way to investigate the pliable nature of your dreams and to fathom more and more deeply how illusory they really are.

For example, you may set yourself the task of walking through walls. After all, the walls are made of the stuff of dreams, so why shouldn’t your dream body be able to glide right through a dream wall without obstruction? But when you try this, you may find to your surprise that you move halfway through the wall and then get stuck! This shows that there’s a whole range of degrees of lucidity. You may know that you’re dreaming, but that knowledge hasn’t yet sunk in enough for you to transform anything in the dream as you wish. (You still may be able to fly, one of the easiest paranormal abilities to achieve in a lucid dream.) In this second phase of dream yoga, like an infant exploring the world of waking reality, you investigate the world of dreaming by interacting with your environment, discovering through experience how all objects in the dream arise in relation to the experiencing subject.

Sustained training in dream yoga is bound to stir up your subconscious, occasionally resulting in bizarre and terrifying dreams. These provide a special opportunity for learning how to overcome fear and gain insight into the illusory nature of dreams, the third phase of this practice. Whenever you feel threatened in a dream—perhaps from ferocious animals, roaring fire, or raging waters—deepen your awareness of the nature of the dream by asking your- self, “How can such illusory apparitions possibly hurt my illusory self?” Then allow yourself to be attacked by the marauder, incinerated by the fire, or drowned in the water. All this is like one rainbow assaulting another rainbow, and insofar as you recognize the illusory nature of everything in the dream, there is no way you can be harmed.

A lucid dream provides you with the perfect laboratory for exploring the nature of the mind, for everything you experience in the dream consists only of manifestations of awareness. According to Buddhism, consciousness has two defining characteristics: luminosity and cognizance. “Luminosity” refers to the capacity of the mind to create, or illuminate, appearances. As you investigate the nature of dream appearances, you begin to comprehend the luminous potential of the mind. Then, while retaining the awareness that you are asleep, you may let the dreamscape fade away, leaving only a vacuous state of consciousness with no object. Now you are left with nothing but the cognizance of consciousness—consciousness with no object other than itself. In the Great Perfection tradition this is understood to be the substrate consciousness, which is characterized by the three qualities of bliss, luminosity, and nonconceptuality. Penetrating the illusion deeper still, you will enter the deepest dimension of consciousness, known as rigpa, or pristine awareness.

According to the Great Perfection teachings, just as the world of dreams emerges from the relative space of the substrate consciousness, so do all worlds of experience ultimately arise from the nondual realm of primordial space (dharmadhatu) and primordial consciousness (jnana). Dream yoga provides one avenue for exploring and waking up to the depths of consciousness and its role in the natural world. When asked what kind of a being he was, a human or a god, the Buddha replied simply, “I am awake.” In our nonlucid dreams, we are mired down in the illusion that we are awake, and we suffer by grasping onto everything in the dream as being absolutely “out there.” In the same way, we are afflicted during the day by regarding ourselves and everything around us as being separate and disconnected. Imagine the bliss of becoming lucid at all times, perceiving all things as luminous displays of the deepest dimension of our own awareness. This is the truth that sets us free.

♦

Check out more on dreaming in this month’s retreat, “A Field Guide to Lucid Dreaming.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.