Brooklyn-born bassist Adam Yauch is now in his fourteenth year as a member of the band the Beastie Boys. The band’s music—a combination of hip hop, hardcore punk, and funk—is provocative and unapologetic, and its concerts have sometimes turned into riots. Since 1980, the group has sold over seven million records in the United States alone. Its last four albums, including the recently released Ill Communication (Grand Royal/Capitol), have all gone platinum.

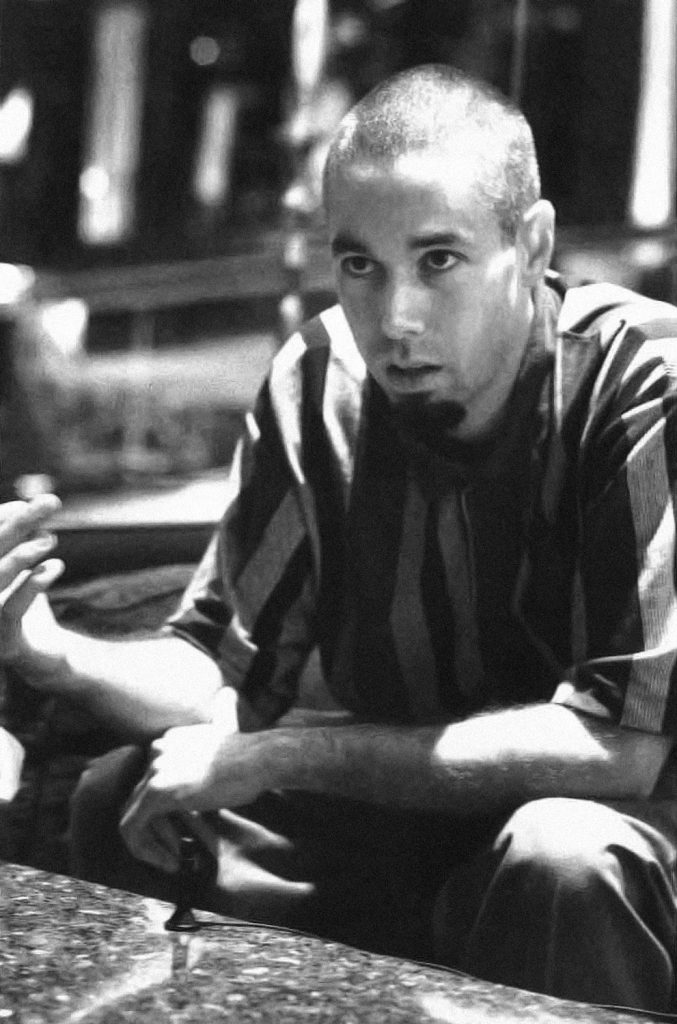

Last summer, the Beastie Boys sponsored the Namgyal monks of Tibet to join them on Lollapalooza, a contemporary music tour with politically conscious concerns. The Namgyal monks performed purification rituals and sacred dances before the beginning of each day’s performances by bands such as Green Day, the Pharcyde, and Boom Poetics. The Beastie Boys also sponsored a booth at Lollapalooza to educate fans about the plight of the Tibetan people, and proceeds from two of their songs are being donated to the Milarepa Fund, a not-for-profit foundation the band established earlier this year “to promote universal compassion through music. ” This interview was conducted on August 5, Yauch’s thirtieth birthday, by Carole Tonkinson, Senior Editor of Tricycle Books. Photographs by Sally Boon.

***

Tricycle: When did you become interested in Buddhism?

Yauch: Just recently. I had been reading about a lot of different religions and spiritual paths and Native Americans for a while. When I was in Nepal and Kathmandu for the second time, a little more than a year and a half ago, I was exposed to Buddhism more. And when I came back to America I started reading books by the Dalai Lama.

Tricycle: What attracts you to Buddhism?

Yauch: The feeling I get from the rinpoches and His Holiness [the Dalai Lama] and Tibetan people in general. The people that I’ve met are really centered in the heart; they’re coming from a real clear, compassionate place. And most of the teachings that I’ve read about almost seem set up to distract the other side of your brain in order to give your heart center a chance to open up. In terms of what I understand, Buddhism is like a manual to achieve enlightenment—there are these five things and these six things within the first thing, and all these little subdivisions. And despite all of that right-brain information, it’s very heart-centered. At least that’s the feeling I get from the Tibetans. Also the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism have been passed down for a long time now. They have that system pretty well figured out.

Tricycle: In a recent issue of Vibe you were quoted as saying you weren’t a Buddhist.

Yauch: I haven’t gotten anyone to give me a really solid definition of what a Buddhist is, so I kind of go back and forth. Sometimes I’ll say I’m a Buddhist in interviews, and sometimes I’ll say I’m not. I study life and people and I think the Buddhist path is a really strong one, really intelligent.

Tricycle: The words that you use in the song “Bodhisattva Vow” [from the album III Communication] adhere pretty closely to a traditional rendition of the Vow. Have you taken that Vow?

Yauch: Yes. But I would like to clarify something. A lot of people have the misconception that taking the Bodhisattva Vow delays enlightenment until all other sentient beings attain enlightenment, and that is not really it. The Bodhisattva Vow means striving for enlightenment to better help all other sentient beings attain enlightenment. That’s an important issue—the objective of that Vow. Being enlightened is the best way to benefit all other beings—from that place you’re able to help more.

Tricycle: Who helped you clarify that?

Yauch: The Dalai Lama—because I was hesitant about taking the Vow. He said something that clarified that point and I said, “Ah, all right, cool.”

Tricycle: This was during the teachings that His Holiness gave in Arizona last fall [1993]?

Yauch: Yes.

Tricycle: Did you have an audience with him?

Yauch: No. That was incorrectly reported in the press. I happened to catch him when he was walking out of a room. It was wild. He grabbed both of my hands and looked at me for a second and I felt all this energy. I just walked to my room and it clicked in my head. I thought, I need to write a song about this.

Tricycle: A lot of Westerners became interested in Buddhism through drugs. Was that part of it for you?

Yauch: I would not say drugs opened me up specifically to Buddhism. But when I first got interested in spirituality in ’88 I was smoking a lot of herb and taking a lot of hallucinogens, and that starts to open you up. It removes your whole doubt system and opens up your chakras [centers of subtle or refined energy], and it becomes easy to start taking in a lot of information. Using drugs is a fairly uncontrolled way of approaching that stuff. Drugs are not something you can go too far with, but you start seeing things that don’t fit into Western teachings and then you have to take it from there. Everyone has a different path. I’m not saying anybody should or shouldn’t do anything, but I realized that drugs weren’t going to go very far for me.

Tricycle: Do you think there’s any connection between a lot of kids taking LSD now and the growing interest in Buddhism among younger people?

Yauch: I don’t necessarily see it in terms of Buddhism specifically. I just see that when people take a lot of hallucinogens and drugs it just starts to open them up a bit, and that’s definitely been going on lately.

Tricycle: Are you still taking drugs?

Yauch: No. I don’t even drink or smoke or anything.

Tricycle: Is that an intentional decision?

Yauch: It started out as something that worked for me, and I’ve gotten more regimented about it recently because it’s nice to have a policy. I’ll go to a party and see some friends and they’ll be like, “Come on, have a beer.” It’s just easier to have a set decision that I don’t drink than trying to decide if I’ll have one beer, or maybe I’ll have two beers and wake up in the morning with a headache. I stopped smoking herb three or four years ago. The one thing about doing hallucinogens is that they open up your solar plexus chakra and allow you to take in the energy of everybody else around you, whether you want to or not. Hallucinogens blow that chakra wide open and you can start taking on a lot of negative energy—worries, jealousy, anger, or whatever other contractive emotions are flying around. I just can’t even mess with that now. I feel a little more in control by keeping my energy separate.

Tricycle: What’s your daily practice?

Yauch: It varies. My daily practice incorporates all kinds of things that I’ve learned. I meditate in the morning and before I go to sleep. These are usually the main times, because before I go to sleep I can get focused on what happened during the day, pull that into perspective, and that’ll make my sleep a little more peaceful. Then I set up what’s going on the next day or get centered for those activities in the morning. A lot of times on tour I don’t get a chance to because it’s so crazy running around.

Tricycle: I was wondering about your attitudes toward women, which seem to have changed so much—the lyrics in “Sure Shot,” for example. What accounts for such a radical change?

I want to say a little something that’s long overdue

The disrespect to women has got to be through

To all the mothers and the sisters and the wives and friends

I want to offer my love and respect to the end.

—lyrics from “Sure Shot”

Yauch: It’s just seeing things from a different perspective. There was a time when we would joke around and say things that were disrespectful of women and think that it was funny, or that it wouldn’t hurt anybody, or that it would be taken with a grain of salt. Then it became clear that that wasn’t the case, and we had to go through the process of taking a step back and realizing how those things affect other people. The lyric in “Sure Shot” is just a statement of that. Even on the last album there aren’t any lyrics that are disrespectful of women, but we went an extra step on this album to make a statement. Mainly where it’s coming from is that I listen to a lot of hip-hop, and there is so much disrespect for women that it’s become standardized, normal. It’s like a blemish in a good song. You hear a good record and you get into the groove and someone’s gettin’ their flow on, and all of a sudden there’ll be some obnoxious lyrics in there.

Tricycle: How did you decide to use “Internal Excellence” as the last two letters in “Beastie”?

Yauch: I don’t know. It was just a goof at the time when we were forming the band. We were just trying to think of the stupidest things we possibly could and it seemed funny. In retrospect it surprises me that it’s come to make sense. I like that.

Tricycle: What’s it like having the monks on tour with you?

Yauch: It’s amazing. They’re really incredible, warm individuals, out there having fun, playing basketball with us and stuff.

Tricycle: Was it your idea to take them on the tour?

Yauch: I was lobbying for it. On tour, they are being sponsored by Artists for Tibet. We also started our own organization, called Milarepa, which is run by Erin Potts, a Tibetan studies major, who is one of the people I met in Kathmandu. She’s on the Lollapalooza tour with us, doing a booth with information about Tibet. The proceeds of two of our songs go to the fund.

I know we can fix it and it’s not too late

I give respect to King and his nonviolent ways

I dream and I hope and I won’t forget

Some day I’m gonna visit on a free Tibet.

—lyrics from “The Update”

Tricycle: In past interviews, you expressed some qualms about appropriating black music. Do you have qualms about taking Tibetan monks out of their culture and putting them on a concert tour?

Yauch: The only worries that come to mind are that kids won’t really be polite to the monks. Also, that some people who have specific concepts about how Tibet should be presented and how monks should be treated are going to be really upset. But in weighing that stuff out the worries are all insignificant. Worries by their nature are misconceptions. To me it’s obvious that it’s for the highest good that the monks be out there. If there are a few kids who disrespect them, that’s no comparison to the amount of good it’s doing. Even if it just sparks something in somebody a little bit, even if they don’t look into it while they’re there, maybe next time they see a documentary on Tibet they’ll say, “Yeah, that’s the thing I saw at Lollapalooza.”

Tricycle: Has being on tour with you affected the monks?

Yauch: For me, the significant thing to keep in mind is that the monks are here learning just like the rest of us. They have chosen a real strong path of abstaining from a bunch of things so that they can remain focused on their spirituality, but they’re working on things just like the rest of us. They’re working toward enlightenment and clearing out misconceptions, and it’s no accident that they have come out on this tour and they are being exposed to whatever they’re being exposed to as part of their path, and, yeah, it’s probably confusing to them here and there, and it’s probably insane. They’re definitely getting exposed to some crazy stuff, but they’re getting some deep learning from it. I strongly believe in interconnectedness, and it’s no accident that these guys are out here.

Tricycle: What’s the craziest thing they’ve been exposed to on the tour?

Yauch: You’d have to ask them. For the most part the fans have been really cool and fascinated by the monks, blown away. They just emanate so much love and compassion that everyone on the tour and the other bands are drawn to them. But once when we played in Philly the kids were so excited about the show that they all started slam dancing and throwing stuff at the stage, trying to knock the monks’ hats off. They had probably gotten drunk in the parking lot. I don’t know whether that stupidity was partly hostile or not. I didn’t actually see it; I heard about it afterwards. I felt really bad and went to talk to the monks, but they were just giggling. But that definitely sent a chill down my spine when I heard that. I thought, Oh no. I couldn’t believe it. But for the most part it’s just amazing. Also, in terms of running a booth, we have supporters of Tibet come up to help us, and sometimes they say, “What the hell are you doing? These are the Dalai Lama’s personal monks and you’ve got them out here in front of these drunken fools.” They’ve just got to chill out. There’s a lot of Western elitism in Buddhism, like Buddhism is theirthing, so there’s hesitation about doing anything that opens up young people to Buddhism. The way I look at it, one million Tibetans have been killed by the Chinese and one million kids will come on this tour. If we can touch those kids, it’ll be worth the effort. A lot of the people who are helping to support Tibet right now are an older group of people, and there’s almost like a fear that the teachings are going to be misconstrued, or that it’s going to be brought in the wrong direction, but it winds up being elitism. It winds up keeping it away from young people, which is really dangerous.

Tricycle: How is it “dangerous”?

Yauch: Some people may be scared that the monks are going to be mistreated on tour or that they need to be treated in a very special way, as if they were in a theater with an audience that is paying them a huge amount of respect and understands what they’re doing. But an attitude like that is never going to wind up freeing Tibet. It’s never going to really spread the dharma.

Tricycle: Is it that the older generation is kind of set in its ways?

Yauch: I think so, but generalizations scare me. It’s just some specific individuals, and their resistance is basically fear. All that stuff comes down to fear, to that insecurity of thinking: Is this going to take something away from me? Am I still going to be able to function the way I’m functioning if this other thing happens? The bottom line of all the problems on this planet and that all human beings are working on is this basic misconception of not-enoughness, feeling like we’re not enough. This is some strain of that, of feeling that if the dharma is presented in this way, or if these other people become interested in this or get excited about it, it’s going to take something away from me. It’s this basic misconception, this feeling of not-enoughness.

Tricycle: Do you see any difference for your own generation?

Yauch: One of the monks said something that’s relevant here. He noticed this huge separation in America between the kids and the adults that doesn’t exist where he comes from, and that there’s a real polarization between adults and youth. Where they come from, when there’s a celebration—or a dance, or a party, or music—the little kids and the grandpas are all dancing and singing together. That’s something this country could definitely grasp hold of. Our polarization of that is more extreme than it needs to be.

Tricycle: Are you hopeful about your generation?

Yauch: I’m pretty hopeful about the evolution of humanity in general. I think that all of us here on the planet at this point have come into these lifetimes and into these bodies because it’s a crucial time in the evolution of the planet and humanity. It’s a transitional phase, and I think that everyone has come in at this time to be a part of that, to be part of the Big Show.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.