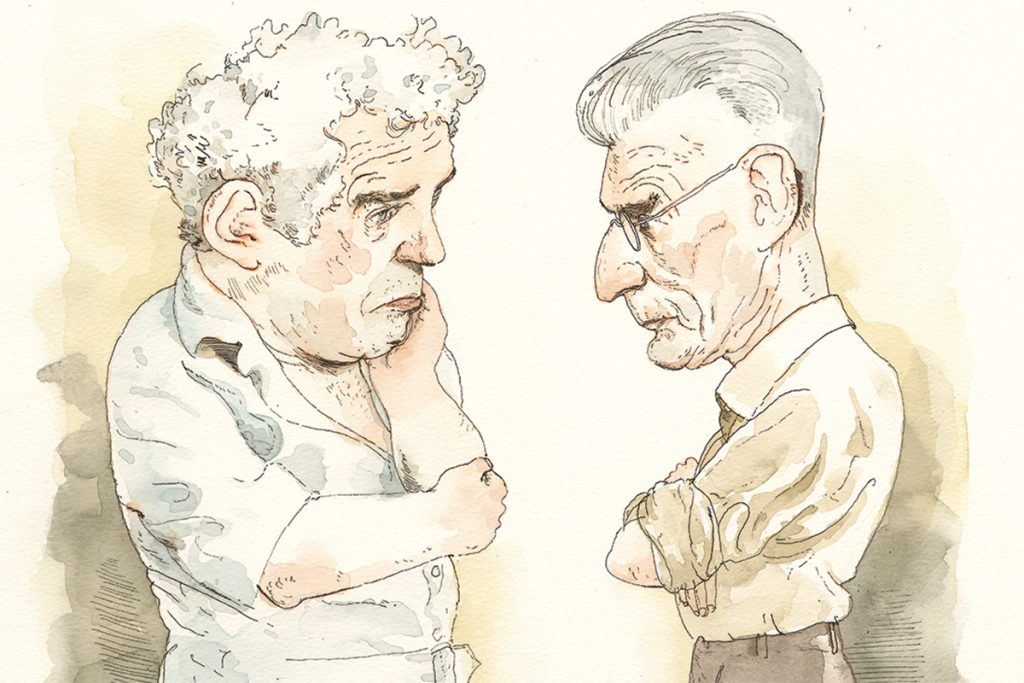

“Form is emptiness and emptiness is form,” we read in the Heart Sutra. It’s a fundamental Buddhist tenet that practitioners can and do spend a lifetime contemplating. In his memoir Four Men Shaking: Searching for Sanity with Samuel Beckett, Norman Mailer, and My Perfect Zen Teacher, the novelist and journalist Lawrence Shainberg takes a unique approach to this elusive teaching, bringing his Buddhist reflections into conversation with two of his friends and literary heroes, Norman Mailer and Samuel Beckett.

In the following excerpt from Four Men Shaking, Shainberg recalls Beckett’s and Mailer’s encounters with the Buddhist ideas he most associated with them.

—The Editors

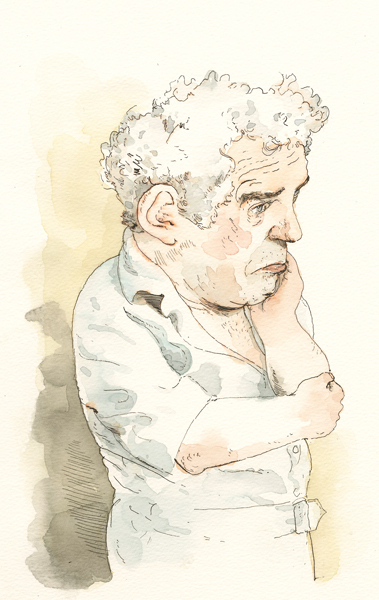

Norman Mailer

One night during dinner at Michael Shay’s, I interrupted an attack on Zen that Norman had mounted even before we sat down and continued while we were waiting for our drinks: “ You know your problem? You confuse nothingness with emptiness.”

“What’s the difference?” he said. “Nothingness is form.”

“What isn’t form?”

“Emptiness.”

“And emptiness? How would you define it?”

“I don’t know. One teacher I know, Bernie Glassman, said that while most people think it means absence of content, what it really means is absence of description.”

“Description?” Mailer nodded, sipping his drink again. The expression on his face was uncharacteristically quizzical.“That makes sense. I’ve got to take a piss. Let’s talk about it when I get back.”

By the time he got back, I’d had a bit more vodka, and he had other things on his mind. Football, as I recall. Which interested me, as it happened, no less than it did him. We never pursued the definition of emptiness I’d offered him, but as I’d see after his death, when I read his last book, the question of emptiness and nothingness never ceased to obsess him. Eventually, it found its way in to his last book, but as I’d see when I read it, my teacher’s definition had been translated into Mailer language and Mailer metaphor—Mailer description—and he had it, in my view, all wrong. Not many subjects escaped the force of his energy and intelligence, but the degree to which he took possession of them was often costly and distorting. Of all the discussions we failed to complete, this may have been the most important. It’s certainly the one that makes me saddest.

New York Magazine published an excerpt from On God two days before Mailer died, when he was in the hospital with a breathing tube in his mouth. He’d had a successful pulmonary surgery a few days before but then contracted pneumonia. When Larry Schiller—an old friend and collaborator—showed him a copy of the magazine, he managed half a smile. His mood after all was not entirely negative. Mike Lennon would report that Mailer had told him that morning he’d had a dream the night before in which he was God and Schiller the devil, and they made a pact to rid the world of technology. He was also engaged in a happy flirtation with a young nurse who had literary ambitions. Before his surgery, she’d sought his advice on a story she was writing, and he’d promised to read it for her.

As I’d see after Mailer’s death, when I read his last book, the question of emptiness and nothingness never ceased to obsess him.

Standing on the other side of the bed, I watched as Schiller presented him with the magazine. This would be the last time I saw him. I had arrived a while before Schiller, so I had a few minutes alone with Mailer and during that precious silence received from him a last note scrawled on a notebook—“Larry OK”—with the K descending pathetically toward the bottom of the page.

The magazine had his picture on the cover, a headshot with white hair flowing. “Mailer on God,” read the headline. I had not seen the manuscript or read the book, but when I did, I found that one section begins with Lennon asking about Mailer’s view of Buddhism. His answer included what seemed to be a description of the night when, during dinner at Michael Shay’s, we’d talked briefly about the difference between nothingness and emptiness.

The difficulty I’ve always had with Buddhism is . . . nirvana. As I see it, the point of existence is not to rise above our petty feelings and leave them behind but, on the contrary, to be able to struggle with those petty feelings in such a way that we lift them into more vigorous feelings. Nirvana always struck me as a place I had no interest in reaching. Whether it existed or not—I had no idea—it did not appeal. I remember talking to a friend of mine who’s a good Buddhist, and I soon fell into a polite rage . . . “You Buddhists always talk about nothingness, at how to arrive at nothingness,” I told him, and added, “As a writer, I can tell you I live with nothingness every minute I’m working. I sit at my desk and for the first half hour there’s nothing—I have to pass through such nothingness in order to come to a few ideas. You’re not really talking about nothingness. Nothingness is an awful state! It’s so empty a state. Why don’t you talk about what it really is you’re looking for, which is the ineffable?”

I felt a great surge of disappointment as I read these lines. Disappointed with Mailer because, as it seemed to me, they showed no understanding of Buddhism, and disappointed with myself because it was obvious that despite our many conversations on the subject, I’d failed to reach him. Surely this indicated an insufficiency on my side as well as his. It was hard for me to believe I was not the “Buddhist friend” he spoke of, that the conversation he described was not the one we’d had in the restaurant after I offered him Bernie Glassman’s definition of emptiness. His reasoning seemed almost bizarre until I realized that the word ineffable was a remnant of it. Its primary meaning, according to the American Heritage Dictionary, is “beyond expression, indescribable.” Thus it was virtually synonymous with the definition of emptiness I’d remembered my teacher offering me and that I had offered Mailer at our dinner. Now, as Mailer remembered it, it referred to the condition he’d recommended to his “Buddhist friend,” who’d so annoyed him with his obsession with nothingness. In effect, he’d completely distorted and inverted our discussion, forgotten the fact that his “Buddhist friend” had often noted that nothingness was not the focus of Buddhism and referred him to a definition of emptiness that was synonymous with ineffable. Finally, too, he had forgotten that the ineffable was not something Buddhists search for, but something they believe to be essential reality, an inescapable truth that is obscured by the dualistic mind. The bottom line, however, was that, inverting our discussion in his memory, he had placed himself in a position of authority, offering—and distorting—the definition I’d offered him. It was as if the obscurations of our conversation as it traveled through his mind were finally a mirror of the circular game we’d played with our thumbs, and I had been his adversary.

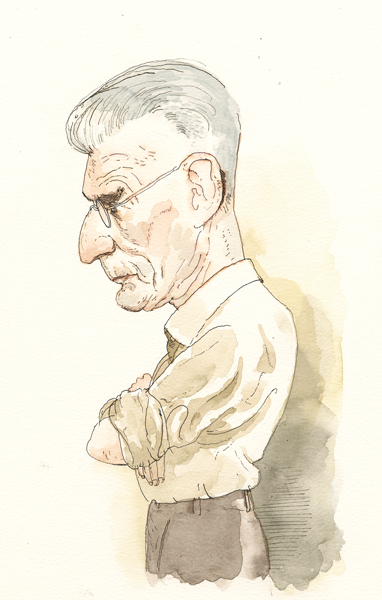

Samuel Beckett

As it happened, one of Beckett’s production assistants on the Endgame rehearsals was a puppeteer who had done several productions of Beckett plays with his puppets as cast. When rehearsals ended, there was a closing party, and he was asked to give a performance of Act without Words. As anyone knows who’s seen it, no Beckett play demonstrates better the

consistency of his vision and the relentlessness with which he maintained it. It’s a silent, almost Keatonesque, litany about the futility of hope. A man sits beside a barren tree in what seems to be a desert, a blistering sun overhead. Suddenly, offstage, a whistle is heard and a glass of water descends. When he reaches for it, it’s raised until it’s just out of reach. He stretches and strains for it, but it rises to elude him once again. Finally, he gives up and resumes his position beneath the tree. A moment later, the whistle sounds again, and a stool descends to rekindle his hope. In a flurry of excitement, he mounts the stool, stretches, grasps, and watches the water rise beyond his reach again. A succession of whistles and offerings follow, each arousing his hope and dashing it until at last he ceases to respond. The whistle continues to sound, but he gives no sign of hearing it.

Like so much Beckett, it’s the bleakest possible vision rendered in nearly slapstick comedy, and that evening, with Beckett himself and a number of children in the audience and an ingenious three-foot-tall puppet in the lead role, it had all of us, children included, laughing as if Keaton himself were performing it. When the performance ended, Beckett congratulated the puppeteer and his wife, who had assisted him, offering—with his usual diffidence and politeness—but a single criticism: “The whistle isn’t shrill enough.”

Not a few critical opinions had been mustered over the years concerning Beckett’s debt to Buddhism, Taoism, Zen, the Noh theater— all of it received with curiosity, appreciation, and absolute denial by the man it presumed to explain.

As it happened, the puppeteer’s wife was a Buddhist, a follower of the path we’re pursuing in sesshin, the path to which Beckett himself paid homage in his early book on Proust, when he wrote, “The wisdom of all the sages, from Brahma to Leopardi . . . consists not in the satisfaction but the ablation of desire.” As a devotee and a Beckett admirer, she was understandably anxious to confirm what she, like many others, took to be his sympathies with her religion. In fact, not a few critical opinions had been mustered over the years, concerning his debt to Buddhism, Taoism, Zen, the Noh theater, all of it received—as it was now received from the puppeteer’s wife—with curiosity, appreciation, and absolute denial by the man it presumed to explain. “I know nothing of Buddhism,” he said. “If it’s present in this play, it is unbeknownst to me.”

Once it had been asserted, however, there remained the possibility of unconscious predilection—innate Buddhism, so to speak—so the woman had another question, which had stirred in her mind, she said, since the first time she’d seen the play. “When all is said and done, isn’t this man, having given up hope, finally liberated?” Beckett looked at her with a pained expression. He’d had his share of drink that night, but not enough to make him forget his vision or push him beyond his profound resistance to hurting anyone’s feelings. “Oh no,” he said. “He’s finished.”

♦

Adapted from Four Men Shaking: Searching for Sanity with Samuel Beckett, Norman Mailer, and My Perfect Zen Teacher, by Lawrence Shainberg © 2019. Reprinted with permission of Shambhala Publications.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.