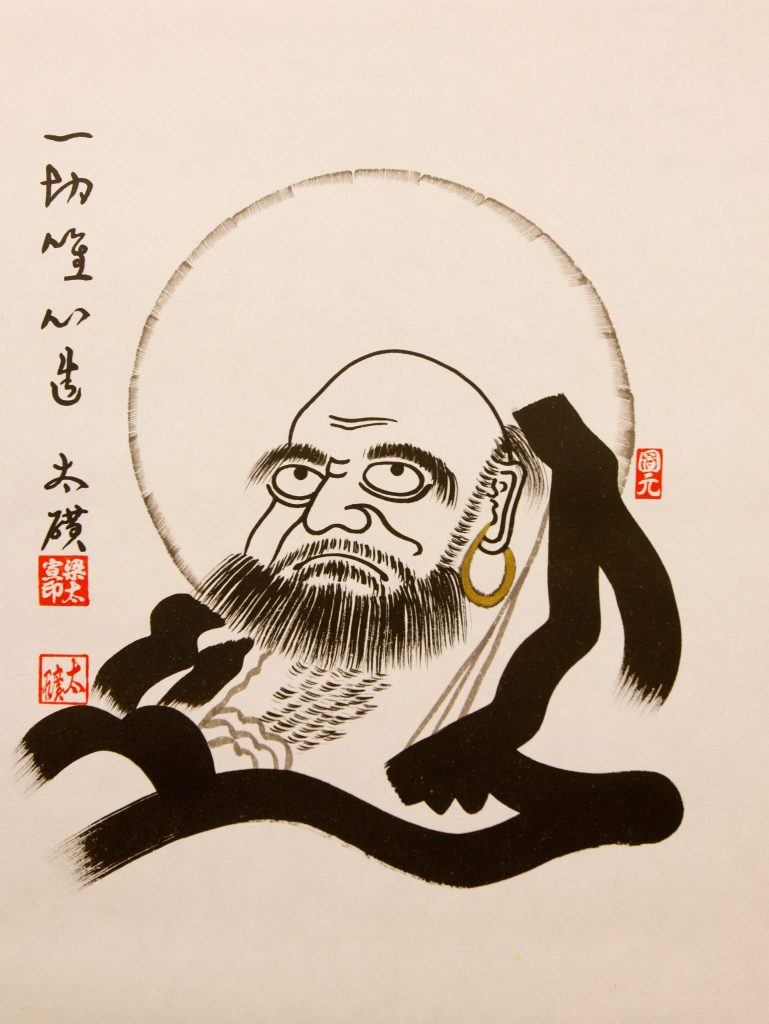

Bodhidharma Pacifies the Mind

Bodhidharma sat facing the wall. His future successor Eko, the second Zen

ancestor, standing in the snow, cut off his arm and said, “Your disciple’s mind

is not yet at peace. I beg you, Master, please pacify my mind.”

Bodhidharma said, “Bring your mind to me and I will pacify it for you.”

Eko said, “I have searched for the mind but have never been able to

find it.” Bodhidharma said, “Now your mind is pacified.”

–Mumonkan Case 41

The legendary first ancestor of Zen, Bodhidharma, was said to be fierce and unfazed, sitting for nine years facing a cave wall. His teaching emphasized no attachment to words and looking directly into the mind to see your true nature. Bodhidharma came to China from India to transmit the dharma. He met Emperor Wu and then retreated to the cave where he faced the wall for nine years. He was so determined that he broke his knees so he wouldn’t get up. It’s also said of Bodhidharma that when he found himself falling asleep in that cave, he pulled out his eyelids to keep awake. That does not sound peaceful.

A popular misconception about Zen Buddhists is that nothing ever gets to them. No matter what happens, they are always chill. But what’s the reality?

When there is no peace in the world, it is challenging to find peace in our own minds. To pacify means to bring or restore to a state of peace or tranquility, quiet or calm. Eko so wanted to show Bodhidharma how serious was his desire to find peace of mind that he cut off his arm while standing in the snow. Various translations of Eko’s request are “please put my mind at rest,” “please silence my mind,” “give it peace,” “give it a rest.” We may say of our own minds, “My thoughts and feelings are driving me crazy—please make it stop! Set me free!”

That’s also the way we may feel about all the wars and conflicts around the world and in this country: I can still hear Rodney King’s heartrending plea, “Can’t we all just get along?”

In reflecting on what it takes to find true peace of mind, I found four themes emerging:

(1) seeing as is;

(2) grounding in nondual wisdom;

(3) avoiding fundamentalist thinking; and

(4) embracing the boundless nature of the bodhisattva vow.

Seeing As Is

Destructive forces are an inherent aspect of life. The basic elements of earth, wind, water, and fire all can create havoc and take life, via storms, floods, earthquakes, melting ice caps, volcanos, raging wildfires, avalanches. Animals, insects, and microorganisms also kill. And when we get into the area of machines we’ve invented going awry, it’s amazing any of us manage to stay alive. I think the reason so many of us lose our cool behind the wheel of a car is that even the slightest mishap could end in death.

Violence erupting among humans can be a physical cry indicating that something needs to be paid attention to. Unresolved trauma or mental distress can cause people to do self-harm by cutting themselves, picking a random fight, or shooting up large groups before killing themselves. Racist violence and hate crimes reveal the unaddressed shadow sides of our culture. Ruthless leaders attacking other countries reveal the three poisons of greed, anger, and ignorance. The whole world can seem like it’s in trauma—individually, nationally, globally, and even our very planet, whose changes in climate are telling us to pay attention.

When there is no peace in the world, it is challenging to find peace in our own minds.

All these are clues to what needs to be addressed. It’s important not to engage in spiritual bypass, but not to do so can seem overwhelming. There may not be more suffering than ever, but our advanced means of communication gives us endless exposure.

When is it time to bear witness? When is it time to turn off the news? We can’t solve all problems, but we can commit to not contributing to the harm. The question for each of us is: What is most beneficial moment by moment?

And how do we not take sides? It’s perfectly natural to have a broken heart for all the lives lost—but it is only one aspect. From a nondualistic viewpoint, how do we include in our hearts those who are causing harm? Intense emotions can make it difficult to think carefully about the implication of one’s actions. So again, we’re back to the desire for peace of mind.

One major way to find peace is to fully see what is, to wholeheartedly acknowledge that the situation or suffering exists, with all its myriad ingredients. This is the peace of deep acceptance—not permanent acceptance—but right here, right now, this is. Yes, this is happening, and I am it. If we don’t start from there, our churning thoughts will just keep avoiding reality. We can’t make change if we can’t see things as they are. One often hears the phrase, “I can’t believe that…” If you catch yourself saying that frequently, look closely at your worldview.

Does This Acceptance Mean There Is No Hope?

I recently heard a Palestinian peacemaker admit he felt hopeless, but it’s out of hitting bottom that new hope can arise. American historian Howard Zinn says:

To be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic. It is based on the fact that human history is a history not only of cruelty, but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage, kindness.

What we choose to emphasize in this complex history will determine our lives. If we see only the worst, it destroys our capacity to do something. If we remember those times and places—and there are so many—where people have behaved magnificently, this gives us the energy to act, and at least the possibility of sending this spinning top of a world in a different direction.

And if we do act, in however small a way, we don’t have to wait for some grand utopian future. The future is an infinite succession of presents, and to live now as we think human beings should live, in defiance of all that is bad around us, is itself a marvelous victory.

Grounding in Nondual Wisdom

This brings us back to Eko’s plea. Where is the mind that needs to be pacified? What happens when we drop all subject-object dichotomies? Where is the mind then? Just sorrow. Just fighting. Just working for peace. At one with all the pain of the world. To paraphrase a koan: to execute every action of our lives with “empty hands.”

In the West, there is often confusion over what we mean in Buddhism by emptiness. It does not mean nihilistic detachment, empty of feeling or thought. For Buddhists, it means empty of inherent existence. Nothing stands alone or is outside the big equation, as I like to put it. Everyone and everything is interconnected and cannot be otherwise!

This emptiness does not lack heart. Quite the opposite: realizing our connection to everything without exception opens us up to the deepest compassion. How expansive can you be? How capacious and inclusive is your great heart?

There is no inside-outside, no us-them. We have not been separate from any conflicts or suffering since the beginning of time. We keep this in mind so that our recitation of the Gatha of Atonement will always be deeply sincere.

Avoiding Fundamentalist Thinking

When we witness harm, it’s easy to see things in clear-cut categories, or to negate the ingredients you don’t jibe with. Though it can be clear that what you are witnessing is causing great harm, it is often less clear how to dismantle and unravel the causes. The fear aroused by the complexity of the situation can lead to extreme viewpoints on all sides.

Fundamentalism or rigid righteousness is extremely dangerous, with its ideas of purity, exclusion, and uncompromising perfectionism. This does not mean one can’t take a strong stand. But doing that can take many forms when you are freed from rigid thinking. A staunch fanatic might say “always speak out,” or “never speak harshly,” or “stick to your view no matter what.” A freely functioning awake peacemaker is alive and available for whatever is needed. There are many different ways we can say stop it. Solutions come with the ability to look more closely and deeply at all the ingredients and all the causal conditions. We should look inside ourselves for our own rigid thinking.

There is no utopia, no idea of a perfect person. Just things as they are now. As Hakuin writes in “Song of Zazen”:

At this moment, what more need we seek?

As the truth eternally reveals itself,

This very place is the Lotus Land of Purity,

This very body is the Body of the Buddha.

Muddy water is the lotus land we live in. Not separate from the muck, the lotus is amazingly resilient, as it lightly floats above the muck, offering color and joy.

Embracing the Boundless Nature of the Bodhisattva Vow

Bodhisattvas don’t need all to be right and peaceful in the world to offer our own peace of mind. However the world manifests itself, we have a job to do. As we often chant, we live to “to stop all evil, to practice good, to liberate all beings, and to accomplish the Buddha way.” The Buddha way reveals the larger picture, the boundless totality of it all.

Nearly twenty years ago, I attended the memorial of lefty activist Irja Lloyd. She was the subject of the documentary Sunset Story, about the free-spirited seniors of Sunset Hall, a Los Angeles retirement home (now closed), who didn’t let advanced age stand in the way of their voicing their concerns about social and political topics. On the program for her memorial was the following prayer that was found in her desk. I haven’t been able to locate the author, but the words have been written on my heart ever since. The prayer echoes the best in humanity that Zinn (and Zen) refers to.

Every line is a shining jewel and reflects beautifully the boundless ongoing nature of the bodhisattva peacemaker. But the words “patient discontent” have always particularly stood out for me.

Discontent—yes, I am brokenhearted and absolutely not satisfied with all the harm and suffering in the world. Patient—I am endlessly on the path to freeing all from the poisons of greed, anger, and ignorance that contribute to that suffering. I am at peace with that discontent, urgently in it for the long haul, lifetime after lifetime, ever awakening to new possibilities.

A Prayer for Our Troubled Times

1. I bow to the sacred in all creation.

2. May my spirit fill the world with beauty and wonder.

3. May my mind seek truth with humility and openness.

4. May my heart forgive without limit.

5. May my love for friend, enemy, and outcast be without measure.

6. May my needs be few and my living simple.

7. May my actions bear witness to the suffering of others.

8. May my hands never harm a living being.

9. May my steps stay on the journey of justice.

10. May my tongue speak for those who are poor without fear of the powerful.

11. May my prayers rise with patient discontent until no child is hungry.

12. May my life’s work be a passion for peace and nonviolence.

13. May my soul rejoice in the present moment.

14. May my imagination overcome death and despair with new possibility.

15. And may I risk reputation, comfort, and security to bring this hope to the children of our world.

♦

This article originally appeared in Water Wheel, Zen Center of Los Angeles’s newsletter. Reprinted with permission.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.