Films like Kundun, Little Buddha, and The Cup have shown that Buddhism has box-office appeal. Now, a new crop of features and documentaries is poised for theatrical release, fresh from the first International Buddhist Film Festival, held last November at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (see www.ibff.org). Coinciding with a major exhibit, “The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art” (see page 102), the festival was organized by the Buddhist Film Society, a Berkeley, California-based not-for-profit set up to increase awareness of the Buddhist experience.

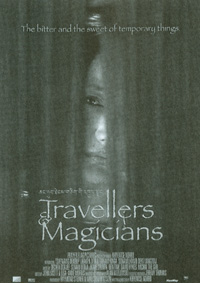

Four thousand people came from around the world for the four-day, fourteen-film event. Among them was Dzongsar Khentsye Rinpoche, the Bhutanese lama and director known as Khyentse Norbu, whose first full-length film, The Cup (1999), was an international success. His second feature, Travellers and Magicians (2003), is the first movie ever shot in Dzongkha, Bhutan’s official language. It had its U.S. premiere at the festival, as did Words of My Perfect Teacher (2003), a documentary by Leslie Ann Patten that follows Khyentse Norbu from London to Bhutan. Asked what he had found most surprising or revealing about Patten’s film, Khyentse Norbu said, “I’m surprised how I still need to dent the bumper of vanity.”

Words of My Perfect Teacher is an often hilarious look at this remarkable lama through the eyes of three of his Western students: a Canadian computer scientist, a British tarot-card reader, and Patten herself, an award-winning American filmmaker now living in Canada. An enjoyable, multicontinent roller-coaster ride, the film offers an interesting commentary on the cultural, psychological, and, at times, spiritual divide between East and West. At one point, Khyentse Norbu comments:

When you don’t have obsessions, when you don’t have hang-ups, when you don’t have inhibitions, when you’re not afraid you’ll be breaking certain rules, when you’re not afraid you won’t fulfill somebody’s expectations, what more enlightenment do you want? That’s it.

The lama consistently lives up to this definition and not to his students’ expectations of him, often to their chagrin. There is irony in the film’s title, taken from Patrul Rinpoche’s classic nineteenth-century text. The theme is established early on with the filmmaker’s voice-over query: “What is he really thinking?” (Patten told the film festival audience that she had made the film to better understand her teacher and that he had let her make it so she would trust him more; it appears that neither happened.)

In the film Khyentse Norbu says, “The truth is so close it’s like our own eyelashes. It’s so close we can’t see it.” And so it is with his students’ relationship to him. In typical Western, analytical (and often neurotic) fashion they alternate between wondering about his intentions, his feelings toward them, and how he operates, and complaining to each other when he keeps them waiting or doesn’t return their phone calls.

What comes through clearly is that Khyentse Norbu practices what he preaches. He moves seamlessly and charmingly between conventions—donning Western clothes to attend a soccer match and wearing a straw fedora with his monk’s robes as he walks down Oxford Street in London—and has clearly transcended codependency. (In his sphere everyone is responsible for his own emotions, his own life, his own awakening.) That Khyentse Norbu is an attentive listener and compassionate teacher is best demonstrated in wonderful vignettes in a London flat, where he reveals some of his internal process as a teacher. The film could use more of those moments. Though the students provide most of the movie’s running narration, the perspective broadens as the film progresses. In one sequence, Bernardo Bertolucci describes Khyentse Norbu (who served as a consultant on Bertolucci’s Little Buddha) as “remarkable,” over footage of the lama on the set with Keanu Reeves. While his Western students obsess about his attentiveness toward them, Khyentse Norbu is revered without question on the other side of the world. When the three students travel with him to Bhutan, they seem nonplussed at seeing their teacher surrounded by devotees bowing deeply in respect. The Canadian student can’t resist a cynical aside: “Osama engenders this same commitment—and offers promises of heaven to his followers.”

In one of many poignant—and telling—moments in Bhutan, Khyentse Norbu blesses the home of a local police chief. He begins chanting in Dzongkha, but suddenly the filmmaker in him takes over. Looking straight into the camera, he repeats the prayer in English—a simple but beautiful homage to the Buddha for the great gift of his teachings. Khyentse Norbu becomes the vehicle for the direct emotional experience that film—like no other medium—can provide, as he transmits the blessing to us, eye to eye.

At first, Travellers and Magicians feels almost like a documentary, so natural is the acting. (In fact, nonactors were cast in many of the key roles.) A parable that is at once funny and dramatic, the film operates on such subtle—and surprisingly sensual—levels that with each twist of the mesmerizing plots (there is a story within a story) we are drawn, like Alice down the rabbit hole, into a fantastical realm of unusual characters and revelations about human nature.

Bhutan itself is one of the characters, giving us a rare look at its pristine landscape. Only recently opened to outsiders, the tiny mountain realm seems to exist out of time, easily lending itself to the fantasy elements of the film. And this is precisely where Khyentse Norbu, its director, begins.

Dondup, played flawlessly by Bhutanese actor Tshewang Dendup, is a restless civil servant stationed in a small mountain village, anxiously awaiting a letter bidding him to come to America. When it arrives, he sets off. Dressed in a traditional gho (Bhutanese dress) and white sneakers, carrying a boom box in one hand and a sky-blue American Tourister suitcase in the other, Dondup cuts a hilarious figure as he hurries out of town. He doesn’t get far, since he’s forced to wait beside the mountain road for the infrequent bus that will take him to the capital.

Dondup is soon joined by an elderly apple picker and a wandering monk (played by the Bhutanese scholar Sonam Kingpa, who was originally contracted to translate the script from English into Dzongkha, then was persuaded to join the cast). With his chances of getting a seat in any passing vehicle now diminished, Dondup decides to outmaneuver the others by moving up the road. When no car or bus comes, he realizes that a man alone on a dark road at night, without food or shelter, is not so self-sufficient after all, and he grudgingly accepts the men’s invitation to share their dinner and fire. Thus, Khyentse Norbu makes the point that only in community can we prosper.

When the monk asks Dondup where’s he going, he replies, “To the land of my dreams.” The monk warns him, “You should be careful of dream lands. When you wake up it may not be very pleasant.” Realizing that Dondup is only trying to escape what he can never lose—his own true nature—the monk begins a tale to wake him up. It is a fable about a restless young man, Tashi (Lhakpa Dorji), who dreams of riding away to a more exciting land. His younger brother slips him a magical potion in the hope of awakening him to the exciting reality of his existing life. Tashi soon finds himself lost in the mountains in a raging storm. He is befriended by an old man, Agay (Gomchen Penjor), who has hidden away his beautiful young wife, Deki (Deki Yangzom). Tashi and Deki start a clandestine affair, but Tashi comes to see how he has been lured into a labyrinth of deception by his own fantasies. The magical tale, of course, parallels Dondup’s idea of what awaits him in the West. By the time the monk finishes, Dondup has grasped the message: Everything you need is right where you are.

Tshewang Dendup’s humorous and expressive performance is reminiscent of Giancarlo Giannini’s in The Seduction of Mimi, and like that film’s director, Lina Wertmuller, Khyentse Norbu shows a knack for tragicomedy with a sociopolitical message. Asked what he will he will do to earn money in America, Dondup says it doesn’t matter, because whatever he does, he’ll make more than he ever would in Bhutan. He may even pick apples, he tells the apple picker, who is incredulous that anyone would give up a respected position to pick apples just for money. Here, Khyentse Norbu reminds us what can happen when we do not value what we have.

For all the messages about dreams, seduction, and deception, the film is a delight, the product of Khyentse Norbu’s inspired direction—and sense of humor. As Dondup quips, “Monks and drunks, who can take them seriously?”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.