Given the threats of environmental collapse, surging white nationalism, militarism, and heedless corporate capitalism, it is understandable if we think that our moment holds an ultimacy. These threats are real. They are our version of the four horsemen of the Apocalypse. Together, they create a menace that is unique in the evolution of living things. We fear that we are in the process of committing collective suicide and that it may already be too late to do anything about it.

Of course, apocalyptic angst is nothing new. We are, in the language of existentialism, “beings-toward-death,” creatures of dread. In Nathanael West’s 1939 novel The Day of the Locust, his artist-protagonist Tod Hackett considers the meaning of a painting he is planning, “The Burning of Los Angeles”:

He wondered if he weren’t exaggerating the importance of the people who come to California to die. Maybe they weren’t really desperate enough to set a single city on fire, let alone the whole country. Maybe they were only the pick of America’s madmen and not at all typical of the rest of the land.

But Tod has a second thought:

He changed “pick of America’s madmen” to “cream” and felt almost certain that the milk from which it had been skimmed was just as rich in violence. The Angelenos would be first, but their comrades all over the country would follow. There would be civil war.

Hackett’s painting is a description of the nation on fire and beyond that, the world. It is a vision that speaks to us now—choking on 12 million acres burning in Australia, gentle koalas dropping dead from the eucalyptus trees—not as a foreboding but as reality. (“This fire is happening to you, too, mate!”) Since this is now our common condition, clinging for our lives on the edge of whatever continent we happen to be on, can anything we do be too radical? Too close to the radix, the root?

Literary critic Frank Kermode would later claim that art like The Day of the Locust was the result of the “apocalyptic imagination.” In his book The Sense of an Ending, Kermode argues that while apocalypse may have its uses in novels (which require beginnings, middles, and endings), it should not be mistaken for reality: witness the long history of “doomsday cults” and their failed prophecies.

Unhappily, our present political and environmental crises offer reasons to rethink Kermode’s conclusions about “endings.” Rather than being a mere religious delusion easily debunked by science or simply laughed away, our sense that the biosphere is dying has science’s imprimatur on it. And indeed science should understand our crisis of life, since it played a major role in creating that crisis in the first place. Where is that mea culpa? If science and technology wanted to stop climate change, they could do so tomorrow by ceasing to aid and abet the technocrats and plutocrats. Without that fundamental revolt, science is what the American journalist Chris Hedges called it: “the handmaiden to barbarity.”

Perhaps Kermode’s conclusion that Judgment Day is only a literary device was true until it wasn’t. Perhaps it’s simply that it took close to a century for Nathanael West’s vision to be not a painting, or a fiction requiring an ending, or a religious neurosis, but a simple fact: the world is on fire. Perhaps we should understand our situation in this same simple way, like the American novelist Henry James, who is reported to have said of his approaching death, “Here it is at last, the distinguished thing.” Perhaps climate catastrophe is death’s Ding an sich; it is the death of death, no one left to die.

Still, as you well know, plenty of people think that our climate emergency is a con, a conspiracy, something hatched among liberals in the “deep state.” Our climate skeptics say that if it weren’t for ecological extremists, we’d see that everything is as it’s ever been … or better than it’s ever been. “There have always been fires and we have always recovered, so not to worry,” they assure us, “the sun will rise tomorrow.” Even some scientists share in this optimism. Evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker claims in Enlightenment Now that people “bitch, moan, whine, carp, and kvetch” about the world. For Pinker this bitching is unreasonable, “given how amazing our world has become.” It’s hard not to recall here the happy insistence of Voltaire’s character Pangloss in Candide that all is for the best in this best of all possible worlds.

But for a quickly growing majority of us, it is increasingly difficult to think “thus has it ever been,” or to kick up our heels with Pinker and Pangloss. The assurances of climate skeptics are seriously damaging if what they mean is that there’s nothing we need to do, no counterforce we need to summon in order to limit or halt our self-destruction.

There is, however, a very different way of thinking “thus has it ever been.” This “other way” provides a description of the human condition, and it provides an explanation for our current existential anxieties; and it may even suggest a way forward.

I’ve been reading in and around Buddhist dharma for 30 years without ever quite thinking that I was a Buddhist. It was more like, “I’m a Buddhist, whatever that means.” I still don’t know what it means. But I’ve always found Buddhist teaching to be astonishingly smart and revealing in the sense that its intention is simply to be true to “the facts on the ground.” It means to tell us the truth, bothersome though that truth may be. It is interested not in what should be but in “what is.” (Thai Forest master Ajahn Chah: “If the world shouldn’t be like this, it wouldn’t be like this.”)

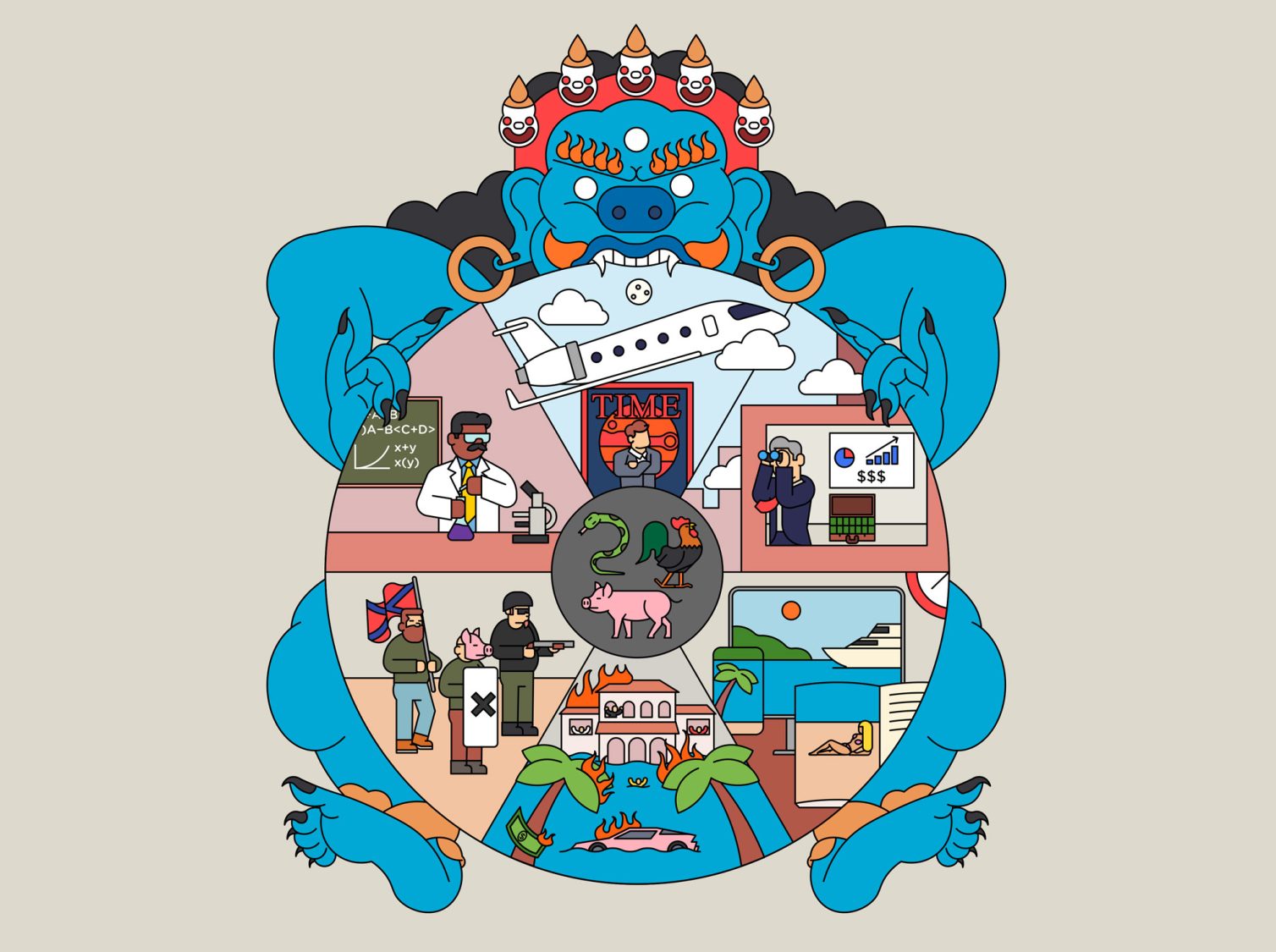

Buddhism tells us very uncomfortable things mostly because it thinks we ought to know them, especially if we mean to find a way to contend with dukkha, suffering, which now must include the ultimate dukkha, the possibility of extinction for all sentient beings, from mussels cooking in the next “blob” of warm ocean water to emaciated polar bears surviving on what they can find in our garbage cans. A particularly powerful depiction of dukkha is the Tibetan Wheel of Life. It is an image of the totality of human life and is often found on the outer walls of Buddhist temples in Tibet for the edification of those not schooled in the rigors of Buddhist doctrine (or, I might say of myself, for the edification of dharma dilettantes).

The Wheel of Life is iconographically dense. There’s a lot going on that is mostly indecipherable to the non-Buddhist. It has many moving parts, wheels within wheels. The movement of the Wheel begins with the ring in the center, depicting the three poisons—anger, greed, and delusion. Some Buddhist commentators think that anger and greed are only aspects of delusion, so the force moving the Wheel—like the core of a nuclear generator—is ignorance. In the Age of Trump, ignorance is manifest, in our face, as if it were a virtue, which our know-nothing president obviously thinks it is. He proudly “thinks with his gut,” which is to say that he thinks through his appetites. Unlike the original nativist Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s, the know-nothings of the present claim to be the party of the know-it- all, a party led by “a stable genius.”

But the wheel within the Wheel that I want to call attention to is the circle of the six realms, the large pie-shaped wedges in the circle beyond the center. One way of understanding the six realms is to say that they are states in which we live and into which we are reborn. The other way of understanding the realms is to say that they depict psychological tendencies that, taken together, describe how and why things are the way things are. But what astonishes me about the Wheel is how well the six realms account for the dysfunction of our world, our polity, now.

At the top of the Wheel is the realm of the gods. This is a rare class of beings—the 1 percent, as we would call them—who keep themselves at a distance from the suffering of others. These are the people, like the first President Bush, who stand in bafflement before a barcode scanner. They don’t know how to buy their own groceries or cook. On a web show spoof, Cooking with Paris, Paris Hilton holds up a spatula and says, “I don’t know what this is.” Paris is perhaps laughing at her own social class, but that doesn’t mean that she thinks that she should know what a spatula is. It’s more like the old saying of the French nobility, “As for living, our servants will do that for us.”

Descending to the right is the realm of the demigods, creatures who are envious of the gods and often fight with them out of jealousy. For us, this is the realm of the businessman (gendered term intended and richly deserved), those fighting up the corporate ladder, concerned only with the accumulation of money and things that, they hope, will one day make them gods. What astonishes me about the Wheel is how well the six realms account for the dysfunction of our world, our polity, now.

Moving on clockwise, the first of three “lower realms” is the realm of the hungry ghosts, people who crave and grasp for things to fill their essential emptiness but who never have enough. Worse, what they do have is indigestible, is dry as dust in their mouths. This is the realm not only of consumerism but also of an enslaving fantasy of consumption: the advertisements in glossy magazines of desirable men and women beside shiny cars, homes, foods, and trendy gadgets. This is the bourgeois art of life hung before us temptingly like the fruit just beyond Tantalus’s bite.

At the nadir of the Wheel is the hell realm, although, since it’s an ever-turning wheel, the hell realm can be at the top and the god realm at the bottom. In the era of climate catastrophe— the Anthropocene—putting the hell realm at the top of the Wheel makes sense, especially since it puts the billionaires at the bottom, in a hell of their own making, multimillion-dollar homes under water in Miami Beach, where their money can’t save them.

The fifth realm is the animal realm. The denizens of this realm are ignorant, angry, and hostile to change. In our version of this realm, patriots profess unqualified love of country, faithfulness to a sordid version of Christianity, hatred of “outsiders,” and hatred of those above them, the elites, which doesn’t mean only the gods. To a degree, they are fond of the gods because the gods tell them what they want to hear—witness the present-day campaign rallies at which people demand “red meat” to confirm their ignorance and feed their hatred. In the animal realm there is a long list of “fighting words,” to which residents respond with resentment and, too often, fists and guns.

And finally, there is the human realm, an ambivalent place of both understanding and “ordinary unhappiness” (Freud). This is where the animals imagine “fighting words” come from— the cultural elites, the snobs, always parading their superior knowledge and trying to enlighten the animals. Of course, humans are bewildered by the resentment of the animals, but there it is anyway, bewildering or not. Humans are curious and creative. Humans are open to change so long as it is the result of attention and honesty. Change, for them, is not a threat but a form of play. If real understanding is going to come about, it’s going to come about among humans.

But even there it’s not all milk and honey, because the realms are not rigid castes. The realms do not have big beautiful walls. They are not places to which we are condemned as if in Dante’s Inferno: “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” Psychologically, the realms represent shared tendencies. For instance, the social slaves of the animal realm think like the gods. They think that they can become gods because wealth is just around the corner, a matter of patience, hard work, and good fortune. In other words, they trust in the system that daily oppresses them. And every realm is “human” in a general sense; everyone has buddhanature, it’s just that this nature is more developed in the human realm. So it is perhaps more helpful to think that there are “human gods,” or “human animals,” or “human humans.” The Wheel presents a typology, an order of types, but it is a dynamic typology.

This dynamism, this permeability of realms, has its own kind of dangers, as our present national predicament shows. The gods and demigods have forged an entente cordiale, turned the animals into a goon squad, and taken the humans hostage (I’m sorry to say it, humans, but you’re just “along for the ride” at this point). Finally, this mess settles uncomfortably down into hell. (As usual, the hungry ghosts didn’t notice anything out of the ordinary because they were in their habitual consumer frenzy out at Nordstrom’s or comparison-shopping on their iPhones.)

My first response to the Wheel of Life was “Oh, I see, so the foundation on which our current political folly rests—like a continental plate over molten rock—is for all intents and purposes unchanged and unchangeable.” It is clearly not the world as it should be; it is the world as it is, difficult though it is to accept that idea. In short, to think that we can “fix” that base situation, or even fix our present abysmal version of it, is, regrettably, a delusion. As a Buddhist friend once said to me, “People who should know better forget that we live in samsara.”

And yet the Wheel of Life is not an invitation to passivity or to the abandonment of hope. It is not about giving up before the inevitable. On the contrary, it is itself a form of resistance.

First, through it Buddhism says to the world, “I see you. I know you for what you are.” Surprisingly, in this the Wheel is not so different from Karl Marx’s Capital. Capital provided for the working class a telling account of the economic system under which it lived. Like the Wheel, it offered self-understanding. Where the two differ is that Capital offers no remedies worthy of the name. Remedies were provided only later, badly, by one dogmatism or another, most dismally “Diamat” (Dialectical Materialism) with its “irreducible laws” of matter in motion, and Stalin’s ruinous version of “Marxist Materialism.” Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that for the most part Marx was a teacher of “what is.”

Second, the partial remedy offered by the Wheel is the possibility of nonparticipation, of leaving the Wheel. Unlike Capital, the Wheel offers not only an account of suffering but also a way to the end of suffering. We don’t have to be passive in the face of what we now know. We can act out of compassion for all who are bound to the Wheel. (Most versions of the Wheel feature a bodhisattva in each realm pointing toward the human realm, pointing toward the possibility of nirvana, awakening.) We can challenge the social conditions into which we have been born, we can teach, and we can offer alternative ways of thinking and living. Buddhism offers a politics of refusal.

Which is to say that Buddhism in the West is a counterculture as well as a religion. Buddhism is not just a revealing analysis, it is also an invitation, just as the ’60s counterculture was an analysis and an invitation, to build community and resilience. It says to others, “Rather than merely spinning with the Wheel, wouldn’t you prefer to live here, in a community based upon honesty and compassion?” There will still be dukkha, but our relationship to it will be changed. Dukkha will be our teacher, and not something that merely hurls us along like dry leaves in a gale.

Finally, of course, since we don’t have the luxury of ignoring the present social and political state of affairs—the “best democracy money can buy,” as the investigative reporter Greg Palast put it—Buddhists can act with others to oppose the money regime. We can join Native Americans at Standing Rock, protest immigrant concentration camps, and join Extinction Rebellion. We can launch dharma-based initiatives, such as the Sacred Mountain Sangha’s Declare Climate Emergency Now.

As I see it, what is essential to Western Buddhism’s purpose is to enlarge the human sphere, offering refuge for those suffering because of our inherited conditions (the toxic cultures into which we have been born). This is a necessary part of “enlightenment,” or “consciousness raising,” as we used to say. Our work is to live in and enlarge the human realm, the human community. The goal for humans is to “get real” if not “get even.” We’re going to try to live well, live by what the Buddha called “right means.” You have the assurances of a dilettante for all this. But then again, with Buddhism, bless it, everyone is a beginner and nobody’s special.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.