Cave in the Snow

Tenzin Palmo’s Quest for Enlightenment

Vickie Mackenzie

Bloomsbury: New York, 1998

224 pp.; $24.95 (cloth)

Cave in the Snow is the biography of Tenzin Palmo, who was the second Westerner to be ordained a Tibetan Buddhist nun and who, like Milarepa, endured a twelve-year retreat in a Himalayan cave. Is there such a thing as a calling? How do you find and recognize your teacher? Is a cave necessary? Can a woman reach enlightenment in one lifetime? Can a woman reach enlightenment at all? These are the brave questions she must have asked herself during her twelve years of solitary retreat. Born Diane Perry in England, Tenzin Palma was eighteen when, during a family trip to Germany, she read a book about Buddhism entitled The Mind Unshaken. In that randomly selected volume, she immediately recognized the path she had been longing to travel. Before finishing the borrowed book, she told her mother, “I’m a Buddhist.”

The announcement did not fall on deaf ears. Her mother, who had considerable appreciation for spirituality, encouraged the daughter’s interest. “That book transformed my life completely,” Tenzin Palma reveals. And what might have seemed like a teenager’s naïve remark soon became an imperative.

She trained with Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche briefly in London before traveling to Dalhousie, India, where she met her guru, Khamtrul Rinpoche. Within a few weeks, she had taken refuge and been ordained—the second Western woman to become a Tibetan Buddhist nun. By 1970, Khamtrul Rinpoche ordered Tenzin Palmo to go further with her practice. “You must go to Lahoul,” he said, referring to the northernmost part of the Himachal Pradesh, where she would find the cave that served as her shelter for twelve years.

She trained with Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche briefly in London before traveling to Dalhousie, India, where she met her guru, Khamtrul Rinpoche. Within a few weeks, she had taken refuge and been ordained—the second Western woman to become a Tibetan Buddhist nun. By 1970, Khamtrul Rinpoche ordered Tenzin Palmo to go further with her practice. “You must go to Lahoul,” he said, referring to the northernmost part of the Himachal Pradesh, where she would find the cave that served as her shelter for twelve years.

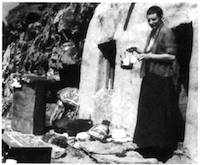

According to Vickie Mackenzie, the cave was tucked under an over-hanging ledge high in the mountains, with a stippled roof so low one had to stoop to enter and a slanting back wall. Beyond the ledge was an almost vertical drop into the Lahoul valley. With friends from Lahoul, Tenzin Palmo bricked up the front of the cave, scooped out the floor, and built a window and door into the front wall and a stone wall around the perimeter of the cave. The total interior measured six feet by six feet. Outside, in the summer, she planted flowers and vegetables. In winter the cave was her isolation booth. More than once she almost suffocated during blizzards, and one year, when her food supply failed to arrive, she nearly starved to death.

Her years in the cave were rich and exciting. “Of course when you do prolonged retreats you are going to have experiences of great intensity…. You get states of incredible awareness and clarity when everything becomes very vivid.” But spiritual materialists are warned when she says: “The whole point is not to get visions but to get realizations. And realizations are quite bare.”

Throughout the book, she talks about the blissful states one falls into on such an extended retreat. “Bliss is the fuel of retreat,” she explains: “You see, bliss in itself is useless. It’s only useful when it is used for a state of mind for understanding emptiness—when that blissful mind is able to look into its own nature. Otherwise, it is just another subject of samsara.” Later, she further encourages: “You go through bliss. It marks a stage on the journey. The ultimate goal is to realize the nature of the mind.” But the journey is difficult. Practice is hard.

After her retreat was broken (inadvertently, by a bureaucrat worrying about the renewal of her visa), Tenzin Palmo returned to the world, living in India and Tuscany. She says that she prefers the hermit’s life to traveling. But she is more like Marpa now than Milarepa—dedicating her life to founding a school for nuns in India with a level of practice commensurate with that which monks enjoy. And like both Milarepa and Marpa, she has begun to teach and to give dharma talks around the world. “But my preference is to be in retreat,” she says, as she flies from one continent to another.

Today, Tenzin Palmo lives in the fragmented world of jets, dharma talks, and fundraising events for her nunnery in India. But to her, every place is appropriate for practice, everything is profound. That’s what this woman’s life, practice, and words say to us. Mackenzie’s well-meaning, if sometimes clumsy, effort to bring this magnificent woman into our lives is to be applauded.

Tenzin Palmo’s words are for all of us. Near the end of the book, she says: “There is the thought, then there is the knowing of the thought. And the difference between being aware of the thought and just thinking is immense. It’s enormous. Normally we are so identified with our thoughts and emotions that we are them. We have to learn to step back and know our thoughts and emotions are just thoughts and emotions. They’re just mental states. They’re not solid, they’re transparent”

Cave in the Snow is full of such extraordinary insights. It is a desert island book—one we can’t very well live without.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.