We begin our retreat by taking the five “precepts,” the principles that lay Buddhists have taken for over twenty-five hundred years to express their commitment to everyday morality. We will make this commitment for the entire twenty-eight-day period. The precepts are simply training tools that help us to stay focused while we cultivate mindfulness. As many people on retreat have realized, the most purifying components of the experience are often the precepts. Our culture rarely provides us with occasion or motivation to relinquish alcohol for a month, and we all struggle with the consequences of the things we say. Taking twenty-eight days to pay special attention to what goes into our bodies and what comes out of our minds is a rare opportunity to live in accordance with our ideals. The five precepts we undertake are expressions of our goodheartedness, our care for ourselves, and our care for others. Consider them skillful means designed as tools for practice, not markers for self-judgment.

The first precept is a commitment to refrain from killing or physical violence. The idea is to use each day, each encounter, as an opportunity to express our reverence for life. This approach counters the tendency to feel separate and apart, objectifying other living beings to such an extent that we’re actually capable of hurting them. The first precept includes all sentient beings—people as well as bugs and animals.

The second precept is a commitment to refrain from stealing—or literally, from the sutras, “to refrain from taking that which is not offered or given.” This means having a sense of contentment; being at peace with what we have; not taking more than we actually need; being grateful for what we have, and so on.

The third precept is refraining from sexual misconduct. This means we resolve not to use our sexual energy in a way that causes harm or suffering to ourselves or others. When we don’t know how to deal with our sexual desire in a skillful way, there are endless possibilities for abuse, exploitation, and obsession. The third precept includes not harming ourselves, in the sense that instead of being driven by our desires, we’re able to make conscious choices.

The fourth precept is about using the power of speech in an ethical way. Traditionally, we commit to refrain from lying, but actually this precept also covers harsh or idle speech and slander. We recognize that our speech does, in fact, have tremendous power. Words don’t just come out of our mouths and disappear. Rather, they’re a very important means of connecting and have lasting effects and consequences. We need to be mindful of how we speak.

The last of the five precepts is a commitment to refrain from taking intoxicants that cloud the mind and cause heedlessness, meaning drugs and alcohol (but not prescription medication). This precept is a traditional way of detoxifying our bodies and minds, but can be challenging at social events where alcohol is considered a means of social connection and relaxation. However, if we are dedicated to maintaining this commitment, these situations often prove to be less awkward than we had feared, and the benefits of keeping the vow turn out to be even more fruitful than we had hoped.

When you find that somehow you’ve broken a precept, the important thing is to take it again. Castigating yourself, or seeing the broken precept in light of the failure or an irredeemable character flaw, is pointless and counterproductive. Instead you might see the beauty and joy in living in harmony, and to use that inspiration to repair the fabric or wholeness in your life.

The Meditation

People have practiced some form of meditation, or quieting the mind, since the beginning of recorded history. All major world religions (and many lesser-known spiritual traditions) include some contemplative component. Vipassana, the type of meditation included in this program, is characterized by concentration and mindfulness. Also known in West as “insight meditation,” Vipassana is designed to quiet the mind and refine our awareness so that we can experience the truth of our lives directly with minimal distraction and obscuration.

The practice of Buddhist meditation can be said to be nontheistic—that is, not dependent on belief in an external deity. Buddhism simply reflects back to us that the degree of our own liberation is dependent on the extent of our own effort. So the Buddha’s style of meditation is compatible with any spiritual path, whether theistic or nontheistic. The practice of mindful awareness is an invaluable tool to anyone seeking spiritual awakening, mental clarity, or peace of mind.

The first pillar of meditation is concentration. Concentration is the development of stability of mind, a gathering in and focusing of our normally scattered energy. The state of concentration that we develop in meditation practice is tranquil, at ease, relaxed, open, yielding, gentle, and soft. We let things be; we don’t hold onto experiences. This state is also alert—it’s not about getting so tranquil that we just fall asleep. It’s awake, present, and deeply connected with what’s going on. This is the balance that we work with in developing concentration.

The other main pillar of meditation is the quality of mindfulness. That means being aware of what is going on as it actually arises—not being lost in our conclusions or judgments about it, or our fantasies of what it means. Rather, mindfulness helps us to see nakedly and directly: “This is what is happening right now.” Through mindfulness we pay attention to our pleasant experiences, our painful experiences, and our neutral experiences—the sum total of what life brings us. The Persian poet Rumi said, “How long will we fill our pockets like children, with dirt and stones? Let the world go. Holding it, we never know ourselves, never are airborne.”

There are five guided meditations in this Commit to Sit challenge that give specific instructions for developing the skills of concentration and mindfulness. The techniques they suggest are meant to be read, considered, and then gently and intentionally implemented into meditation periods.

Cultivating a daily meditation practice

The emphasis in meditation practice is on the word “practice.” It’s a lifelong journey, a process of learning to come back to clear, unobstructed experience. Checking in daily with this profound practice will yield the greatest impact throughout your life.

Just as painful habits take time to unravel, helpful habits take time to instill. Here are some suggestions to help you establish a daily meditation practice. None of these ideas is a hard and fast rule; try using them instead as tools to support your intention.

Plan to meditate at about the same time every day. Some people find it best to sit right after they get up, while others find it easier to practice after a shower and coffee; your second practice could be in the afternoon or at bedtime. Experiment to find out what times work best for you

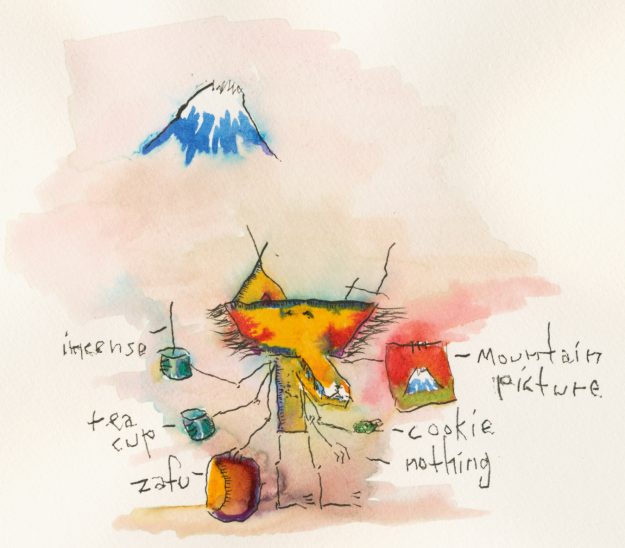

Find a quiet place to meditate. It could be in your bedroom or living room, in a basement or attic, or on a porch. Wherever you sit, pick a place where you can be relatively undisturbed during your meditation sessions. Try to keep your space free of clutter. If you can’t dedicate this space exclusively to meditation, make sure you can easily carry your chair, cushion, or bench to and from it each day.

Some meditators like to bring inspiring objects to their meditation space: an image, some incense, or possibly a book from which you can read a short passage before beginning.

Keep it simple. The purpose of your practice is not to induce any particular state of mind, but to bring added clarity to whatever experience you’re having in the moment. An attitude of openness and curiosity will help you to let go of judgments, expectations, and other obstacles that keep you from being present.

♦

Commit to Sit: Tricycle’s 28-day meditation challenge

|

|

Introduction |

Working with Aversion |

The Five Precepts |

Working with Metta |

Week 1: The Breath |

Working with Sense Doors |

Week 2: The Body |

Seated Meditation Tips |

Week 3: Emotions & Hindrances |

Working with Hindrances |

Week 4: Thoughts |

Meditation Supplies |

Posture |

7 Simple Exercises |

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.