Buddhists in the United States include fifth-generation Americans of Chinese and Japanese heritage, second-generation Korean-Americans, recent immigrants from Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, and Cambodia and their American children, along with converts from European, African, and Latino backgrounds. As with other groups, Buddhists with common cultural and sectarian orientations have tended to stick together. With the end of the melting pot ideal, issues that once addressed racial and cultural diversity have been redefined in the political terms of multiculturalism. As this special section on Dharma, Diversity, and Race suggests, the views of Buddhists from different races and traditions reflect the society at large.

I was named after Frederick Douglass, though my parents left the last “s” off my middle name. “We figured that we’d give you an option,” my father half-joked. “If you wanted to you could always say you were named after Douglas MacArthur.”

Actually, it was hardly ever a problem. None of my white friends would’ve known that I Frederick Douglass was an escaped slave who became a leading abolitionist. And none of my black high school friends who might have known would have made the connection. My childhood nickname had long since taken over—I was Ricky and still am Rick.

But one person did know. And she thought it was the funniest thing she’d ever heard. She was my social studies teacher at Andrew Jackson High School in Queens—a black social studies teacher. When she read my name on some official document, she said to me (after class): “Now isn’t this something! I have heard of black—she probably said “Negro”; we’re talking 1958 or so—kids called George Washington This and Thomas Jefferson That. But this is the first time I’ve ever heard of a white boy being named after a black!” And she laughed, with real delight, and I felt that the name I bore, if not exactly secret but still in hiding, was an occasion for pride.

But the most telling part of this tale, so to speak, is that, if it suited me, I could keep it a secret. The bureaucrats who stamped driver’s licenses and entered Social Security numbers would have been the last to know, and anyhow, the life story of Frederick Douglass was hardly on the required reading list in those pre-multicultural years. My secret was my own—I could pass.

This, of course, is also a characteristic of white Buddhists. In America, white Buddhists may have adopted an Asian teaching learned from Asian teachers; they may go by Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Tibetan, Sinhalese, or Vietnamese dharma names; they may wear robes and shave their heads; speak with an Anglo-Indian or Tibetan accent; eat soba or mo-mos, sip green tea or chai, but the fact is that when and if it becomes necessary or convenient—in the event, say, of a right-wing fundamentalist Christian coup—white Buddhists could shuck it all and emerge, like Clark Kent knotting his tie as he exits the phone booth, safe and sound.

People of color, of course, cannot “pass.” They do not have the phone-booth option. Asian-Americans, be they recent immigrants or third-generation sansei, are always in peril of being placed by color and race. No matter that they may be Christian, as perhaps more than half of Asian-Americans are, or that they may be named George and live an exemplary middle-American suburban life speaking not a word of their ancestors’ tongue, they are still vulnerable to the psychic ambush of some chance acquaintance remarking blandly one fine Sunday morning that they sure do speak English well.

This racism has been the nightmare squatting at the heart of the American dream since the very beginning. Judge Charles T. Murray of the California Supreme Court laid bare the underlying pattern in 1854, just one year after the Sze Yip Trading Company built America’s first Buddhist temple in San Francisco’s Chinatown, when he disallowed the testimony of a Chinese eyewitness to a murder involving two white men. Ever since the time of Columbus, said the judge, “the American Indian and the Mongolian or Asiatic were regarded as the same type of species”—which is to say, less than human and without white rights. We can see the same pattern again in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, “the first departure from our official policy of open laissez-faire immigration to be made on ethnocultural grounds,” as Stuart Creighton Miller points out in The Unwelcome Immigrant, and, of course, in Executive Order 9066, which relegated 110,000 Japanese-Americans to internment camps in 1942.

These are all fairly straightforward examples of racism: part—a very large part—of who and where you are in society is defined by what color you are. A deeper and perhaps equally powerful aspect of racism, however, is the power to define, always the paramount power in a racist society.

It’s hardly surprising, then, that in the ongoing discussion about the meaning of an emergent “American Buddhism,” it is mainly white Buddhists who are busy doing the defining. Nor is it surprising that they’re defining it in their own image. At the moment, to this participant-observer at least, it seems that American Buddhism as defined by white Buddhists is based on a strenuous, if not athletic, practice of meditation and is becoming increasingly democratized, psychologized, and socially engaged. There is also a growing concern with moral standards and norms, as well as a receptiveness to feminist critique.

No doubt I exaggerate. The Americanization of Buddhism of which all American Buddhists are both cause and effect is inevitable. And much of it may well be a necessary and salutary corrective to out-of-date Asian hierarchies and patriarchies. But like all positions, this one is not the whole truth. By insisting that they and they alone get to define what American Buddhism is, white Buddhists end up losing a great deal.

The division may stem from the fact that the great majority of Chinese and Japanese immigrants who founded the first Buddhist temples in America were followers of the Pure Land schools. These schools focused on the figure of Amitabha, the bodhisattva who had vowed that anyone—prince or peasant, holy man or hunter—who uttered his mantric name would gain rebirth in the Pure Land, a western paradise where conditions are especially favorable to gaining liberation. It was also taught, however, that for those with the eyes to see it, the Pure Land could be found right here and now, in this very world.

A small number of white Buddhists were drawn to the Pure Land teachings as early as 1899, when five white Californians joined Japanese missionaries to form an organization called the Dharma Sangha of Buddha and publish an English-language journal called The Light of Dharma. But for the most part, it was the dramatic rigors of Zen that galvanized the first and most zealous white Buddhists. Psychedelics had more to do with this than most would like to admit these days, but the mind-blowing intensity of drugs in the sixties gave practitioners a taste, perhaps one should say a thirst, for extreme experiences. White Buddhists who came of age during the sixties wanted enlightenment—and they wanted it now.

In contrast, the Pure Land approach seemed very low-key and not all that exciting. The few white Buddhists who wandered into a Jodo Shinshu (Pure Land) Buddhist Churches of America temple found something that at first glance reminded them all too much of what they had left behind: families in pews wearing their Sunday best, listening to a sermon by a minister and singing hymns. Ironically, the very success of the Japanese-American Buddhist Churches of America formed a barrier for the first generation of white Buddhists.

In Asia the disciplined and regular meditation approach was largely limited to monks, but in America meditation came to be practiced more generally in co-ed dharma centers, lay meditation societies, and communal retreats. This has led to certain inherent contradictions. As Suzuki Roshi once said, scratching his head: “You Americans are not quite monks and not quite laypeople.”

Buddhists in the United States include fifth-generation Americans of Chinese and Japanese heritage, second-generation Korean-Americans, recent immigrants from Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, and Cambodia and their American children, along with converts from European, African, and Latino backgrounds. As with other groups, Buddhists with common cultural and sectarian orientations have tended to stick together. With the end of the melting pot ideal, issues that once addressed racial and cultural diversity have been redefined in the political terms of multiculturalism. As this special section on Dharma, Diversity, and Race suggests, the views of Buddhists from different races and traditions reflect the society at large.

Nevertheless, a bias toward hard-style monastic and yogic practice has remained the central focus of so-called “American Buddhism.” When Suzuki Roshi came to America to minister to the Soto Zen mission in San Francisco, it is said that he found Japanese-American Buddhists to be interested only in social affairs and devotional approaches. Only the young and wild Americans were willing to undergo the rigors of true Zen training. And so, leaving the Japanese-American Soto Zen mission, Roshi forged the brave new world of American Zen. Indeed, most white Buddhists define their meditation approach as the “real” Buddhism and tend to dismiss the devotional Pure Land forms as exemplified in ethnic or immigrant Buddhism.

Today there is a whole new wave of Asian immigrants—many but not all of whom are Buddhists. There are Vietnamese, Thais, Cambodians, Burmese, Taiwanese, mainland Chinese, and most recently, even a few thousand Tibetans. Unlike the first Chinese and Japanese, however, these Asian immigrants are entering a country that has, for the first time in its history, an active if small Buddhist population. No doubt there have been many instances of fellowship, communication, and help between the various groups, but such instances remain more the exception than the rule. In general, there is far less fellowship and communication among these communities than one would expect. Today the divergence between white American Buddhists and Asian-American Buddhists is as wide as or perhaps even wider than it was in the past. The Asian-American Buddhists are going one way, the white American Buddhists another. Looking at it this way, we see not one but two American Buddhisms.

Much of this split probably stems from the natural ethnic fellowship of an immigrant community in which Buddhist temples have functioned first of all as cultural and community centers. Activities are conducted in Thai, Vietnamese, or other non-English languages, and many white Buddhists are reminded of the empty, required rituals of their own childhood churches and temples—just what they fled from into Buddhism. “It’s just like church,” is a common comment.

Of course there are many reasons for this situation. Some of them are obvious enough: by definition, ethnic Buddhism serves and protects the interests of a particular community within the bubbling cauldron we used to call a “melting pot.” And it is true, as well, that “Asian-American” and “immigrant” hardly reflect unified groups—deep historical and ethnic animosities exist between Vietnamese and Chinese, Koreans and Japanese, and Burmese and Thais, to name just a few. Furthermore, there do seem to be very real differences in styles of practice, so that the division we see may be not so much racial as it is a continuation of an ongoing sectarian dialectic about how best to realize liberation, with the white Buddhists tending toward the “self-power” of Zen and the Asian-American Buddhists tending toward the “other-power” of Pure Land, though even that distinction hardly holds in the Chinese and Tibetan traditions.

Ethnic Buddhism is rooted in, indeed inseparable from, community. It is a Buddhism that is part of a culture, and therefore no big deal, not self-conscious. If the Asian-American Buddhists seem to lack the bent-for-enlightenment zeal of some white Buddhists, they also lack the self-centered arrogance that all too often goes along with it. I remember the teaching offered me by a Vietnamese woman when she felt my irritation that a weekend retreat at a temple had been delayed by a wedding. “Hey, take it easy,” she said. “We Buddhists got to take it easy, you know.”

It may even be that certain aspects of Asian-American Buddhism can suggest alternatives to the white American Buddhists caught in the dilemma of practicing in a monastic style while living a nonmonastic life. Shinran, the founder of Japanese Pure Land, was a revolutionary who insisted that the liberating insights of dharma were fully available to the ordinary man and woman—even, especially, if they fished for a living. And, in the Pure Land tradition anyway, the teachers who continue to insist that this is so are neither monks nor priests nor rinpoches nor roshis but married “ministers.” At the very least, this model, which has existed right in front of our noses for more than one hundred years, may be worth contemplating, both for its successes and its failures.

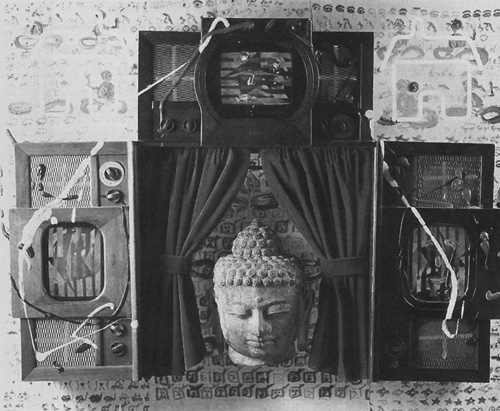

As for the devotional aspect—a little more of that might not hurt white Buddhists. And a deeper look at what is going on in Pure Land traditions wouldn’t hurt either. It may look like church, it might even sound like church. But look and listen again. The chanting that I’ve heard in Vietnamese and Korean temples may well contain the seed syllables of our own Buddhist spirituals—certainly the intensity of feeling does. And if we take a closer look, we find that Amitabha is not a monotheistic Judeo-Christian creator God and the Pure Land is not a Judeo-Christian heaven. We would do well to remember that no less a Zen patriarch of American Buddhism than D.T. Suzuki wrote his last book on Pure Land Buddhism, pointing out that if you stop looking for it, the Pure Land is right here and now. I remember asking one minister what the core of the Jodo Shin (a Pure Land Buddhist sect) teaching was. He thought about it a little, then said that what he told the kids in Sunday school was that the core of it was gratitude. “Every day,” he told me, “we say, ‘Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.'” They say this in gratitude to the bodhisattva Amitabha, who has made a vow to conduct all who have called on him even once to the Pure Land, where practice and hence enlightenment are much easier and which, many say, is right here and now.

But racism, as it turns out, is also here and now, and a ubiquitous component of our national ego. When we deconstruct it in the hard light of meditative awareness, it is the problem of the other—or the terrifying apprehension of the other—which in itself is neither more nor less than a reflection of the old Buddhist problem of self. As usual, we will be brought back to the penetrating insight born of meditative awareness. If we could drop all our self-centered striving for enlightenment we could see what is right in front of our eyes and nose: with nothing to define and no one to define it, a manycolored, multi-cultured, pluralistic Pure Land with room enough for all.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.