RINGLEADER OF THE TORMENTORS MORRISSEY Sanctuary Records, 2006 $18.99 (CD)

THE NUN IN ORANGE robes seemed unimpressed by my question, but I was not trying to be a smart-ass. I’d left after her talk for a solitary cigarette, the only dharma student that night who cared to take a few minutes in the bitter English air for a nicotine hit. Her talk on samsara had struck a chord deep inside me when she suggested that pop music replays the circuit of birth and pain, selling us stories about falling in love and songs about when I woke up this morning and my baby left me. Yes, she did have a point. Pop songs tell us—with hectoring insistence since hip-hop’s unfortunate love affair with gross materialism—about the things we need to buy; and pop songs complain that I can’t get no satisfaction. Pop tells us that we won’t get fooled again; and it tells us that we should make a better world.

The different stories go round and round, and you can get stuck in the grooves.

“This pop as samsara idea is really quite interesting,” I had said, “but aren’t there some artists who explore and expose the cycles of suffering?” And that was the end of the conversation.

I was thinking of The Smiths, the band who made a career out of miserablism, and whose singer Morrissey went solo in 1988, releasing a series of fine albums whose main purpose sometimes appears to be pointing to the abiding veracity of the First Noble Truth. His first post-Smiths release was simply titled Viva Hate; it was a superb debut, and it concluded with the notorious track “Margaret on the Guillotine,” a song that fantasized about the execution of the British prime minister. The second solo record to attain Smiths-like brilliance was Your Arsenal (1992), which contained a song with the glorious title “We Hate It When Our Friends Become Successful.” (Elvis Costello once said that “Morrissey sometimes brings out records with the greatest titles in the world which, somewhere along the line, he neglects to write songs for.” True. Of Costello as well.) And now, a mere fourteen years later, Morrissey has made his third solo record of note: Ringleader of the Tormentors.

The titles alone render Morrissey a poor candidate for the role of poster child of Buddhist pop, but then again, he is a relentless sufferer and an aggressive vegetarian—Meat Is Murderis the title of one of the most accomplished Smiths albums. In any case, most of the music that passes for Buddhist pop these days consists, as far as I can tell, of interminable pseudo-trancelike drum machine-and-synthesizer loops punctuated by occasional hints of wailing and/or chanting. It’s “spiritual!” It’s got the Awakened One on the cover! It’s Buddha Bar!Even the otherwise dependable Jah Wobble loses sight of his talents once he calls his latest record Mu, feeling therefore obliged to regale us with a track titled—say it with me—“Samsara,” wherein drum machines and synths do indeed loop, and Wobble meaningfully intones that title, over and over again, until you truly realize the nature of suffering. What’s next? Stephen Batchelor with The Chemical Brothers at the turntables?

WHEN I TOLD my friends about the excellence of the new Morrissey album, about how strong the songs are, how wide-ranging they are in style, how fine Tony Visconti’s production is, how Morrissey almost makes a theist of you when he sings “Dear God Please Help Me,” I was met with indifference and hostility. I was told that Morrissey cannot sing. But this man has one of the most instantly memorable voices in the history of popular music! I was told that his songs are depressing. As if Morrissey himself had cast suffering into the world! And I was asked if he’d cheered up yet, because it was undignified for a successful man of forty-six, one so loved by his fans, to be so moody.

To which I say that pop music at its best is surely little more than an exercise in public suffering. And Morrissey does it very well. The opening line of Ringleader of the Tormentorsmakes it clear that existential angst will not be made pretty: “Nobody knows what human life is/ Why we come why we go.” Not content with titling a song “Life Is a Pigsty,” Morrissey insists on lacing the statement with contempt: “Life is a pigsty/ And if you don’t know this/ Then what do you know?” There is perhaps more than a hint of the importance of living in the moment on “In the Future When All’s Well.” (“Every day I play the same sad game/ In the future when all’s well.”) But the song’s conclusion insists: “The future is ended by a long, long sleep.” When Morrissey sings about sex, he says: “There are explosive kegs between my legs/ Dear God, please help me.” Rocking around the clock, this is not.

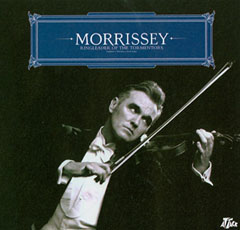

As usual, the album is packaged with anachronistic recyclings—Morrissey pictured as a concert violinist, on a scooter, with a camera. And he poses on the back cover (with SMASH BUSH graffiti on the wall behind him) looking like one of the sixties movie icons that used to adorn The Smiths’ albums, and with a cycle of sorts—a Vespa. He’s taking a photograph of someone, we don’t know who. His lover, perhaps? Is it also for his lover that he mimics playing the violin on the front cover? It’s a parody of the Deutsche Grammophon record label logo, but still, he is serenading someone. Rock critics and Morrissey fans may speculate ad infinitum, but it seems clear that the “you” addressed on so many of these songs potentially includes a lover, the listener, and God. It is of course tempting to conflate this Unholy Trinity, and never more so than on “Life Is a Pigsty.” Here Tony Visconti’s production winks at us with its echoes of mid-seventies David Bowie (whom Visconti produced back then, and more recently) as Morrissey poignantly declaims: “I can’t reach you anymore/ Can you please stop time?/ Can you stop the pain?” Well if God can, He appears not to be listening to Morrissey.

There will be many listeners and fans (and maybe a few critics) who wish they could put one of popular music’s most important artists out of his misery. But then he delivers a samsaric flourish that cuts through the assumption that pop music may not deliver us from dualities: “I feel too cold/ And now I feel too warm again/ Can you stop this pain?” Oh, that pain. Well, you need to follow the breath, mate. But this song is not done with us yet, for its conclusion returns us to pop’s eternal theme: “Even now, in the final hour of my life/ I’m falling in love again.”

So Morrissey has found love, at last; but he’s still suffering. Nobody wants to hear this. Especially if it’s true.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.