Skeletons, whether lying down in a cemetery, hanging over the branch of a tree, standing, walking, dancing, or in a pair, always represent impermanence and death in Himalayan art. This goes back to the Pali canon’s meditations on the stages of corpse decomposition. The skeleton is the ultimate decomposition; there’s really nothing left, unless you grind up the bones.

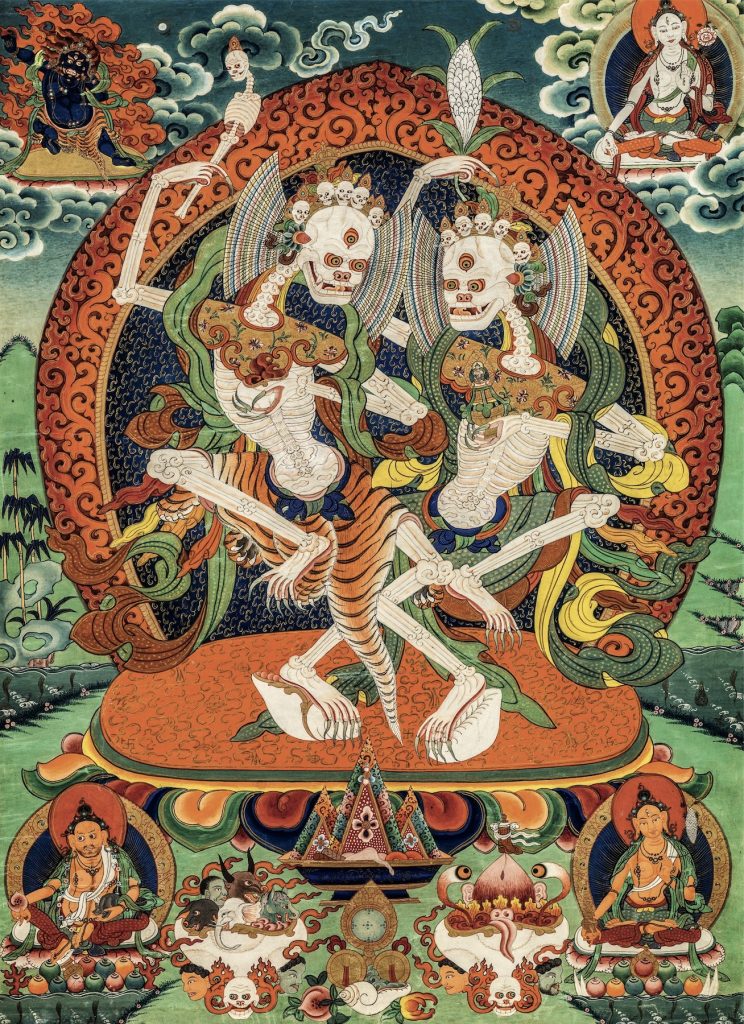

The dancing skeletons, which we see here, are properly named in Sanskrit: Shri Shmashana Adhipati, or “Revered Lords of the Cemetery.” The term Chitipati, or “Lord of the funeral pyre,” is also commonly used nowadays, but this word does not exist in any of the ritual texts or the root tantras.

The Shri Shmashana Adhipati comes from a text called The Secret Mind Wheel Tantra, part of the Chakrasamvara cycle of tantras. There are three ways to view these figures. The first is as meditational deities. In this practice, they are actually protector deities and sometimes wealth deities. The second is as dancing figures, which we will discuss more below. The third area is cemetery scenes. In depictions of these scenes, it’s naturally very common to have one or two or more skeletons. These skeletons represent impermanence and signal that the cemetery is a frightening place where you have to be even more aware, more conscious, because it may be full of zombies and all sorts of terrible things.

There is a Shmashana Adhipati dance in the Sakya tradition (one of the major schools of Tibetan Buddhism), but it was developed only about 250 years ago. It doesn’t go back 900 years, as the practice from The Secret Mind Wheel Tantra does. Other traditions might have adopted some form of skeleton dance as well.

You would normally see images like these in the protector chapel of a monastery or a temple. They would be community commissions for the traditions that have Shri Shmashana Adhipati as one of their main protectors. For an individual devotee of this practice, you would likely have a small painting done, or a small clay figure or small sculpture.

The dancing skeletons we see here, in a painting dating to roughly the 19th century, are meant to be frightening. Each dancer—one male, one female—holds a fused spine staff and a skull cup full of blood. The female can also hold a sheaf of barley or rice in her right hand, signifying abundance, and in her left hand, she has a golden vase, representing wealth. The skulls they wear represent the five aggregates and the five wisdoms, meaning complete Buddhahood. That makes them wisdom deities rather than worldly deities. The landscape where they exist is not one you’ll see out your window. It’s not part of samsara. They are emanations. This is an interesting subject: Which deities are alive and which are emanations?

The skeleton is the ultimate decomposition.

Maybe the only unique thing about this particular depiction is that one figure stands on a conch shell and the other on a cowry shell, which are believed to have protective properties. They stand on a sun disk, representing the thought of enlightenment, and they’re completely surrounded by flames of pristine awareness.

They both wear hair ribbons, even though they don’t have any hair, and this is an artistic convention, to add visual interest to the composition. These hair ribbons may have developed out of the dance mentioned above rather than being part of the iconography. All of these decorative ribbons may be a case of art imitating life, because we don’t have those in the original images of Shri Shmashana Adhipati. They appear only in more modern images.

As far as the oldest images go, we can go back to the 13th or 14th century, but we will not find the skeleton deities as central figures. They will appear as secondary figures within a larger composition along with other protectors, because it was not a major practice. Skeleton figures generally appeared in the lower corners of paintings back then, since the practice was more a minor protection practice that required initiation and a twenty-one-day retreat.

These figures were pulled to the fore at some point later. And the open landscape behind them, with floating figure paintings, appears only in the modern era, say the last few hundred years or so, beginning in the 17th century.

There is a tremendous amount of artistic variation in the iconography of the two dancing skeletons. The artist has a fair amount of flexibility to place the arms and legs in different positions. The male should be dancing on his right leg, and the female on the left, which is the case here, but beyond that there is a lot of interesting artistic invention and variation, if you look at a number of these images.

They’re not as static as a lot of forms that we’re used to, as with Avalokiteshvara or Kalachakra. There’s an acceptance in these depictions for the artists to be creative. There’s a certain freedom that comes out and makes for very entertaining images.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.