In Tibetan Buddhism, “bardo” is a between-state. The passage from death to rebirth is a bardo, as well as the journey from birth to death. The conversations in “Between-States,” Ann Tashi Slater’s Tricycle Online series, explore bardo concepts like acceptance, interconnectedness, and impermanence in relation to children and parents, marriage and friendship, and work and creativity, illuminating the possibilities for discovering new ways of seeing and finding lasting happiness as we travel through life.

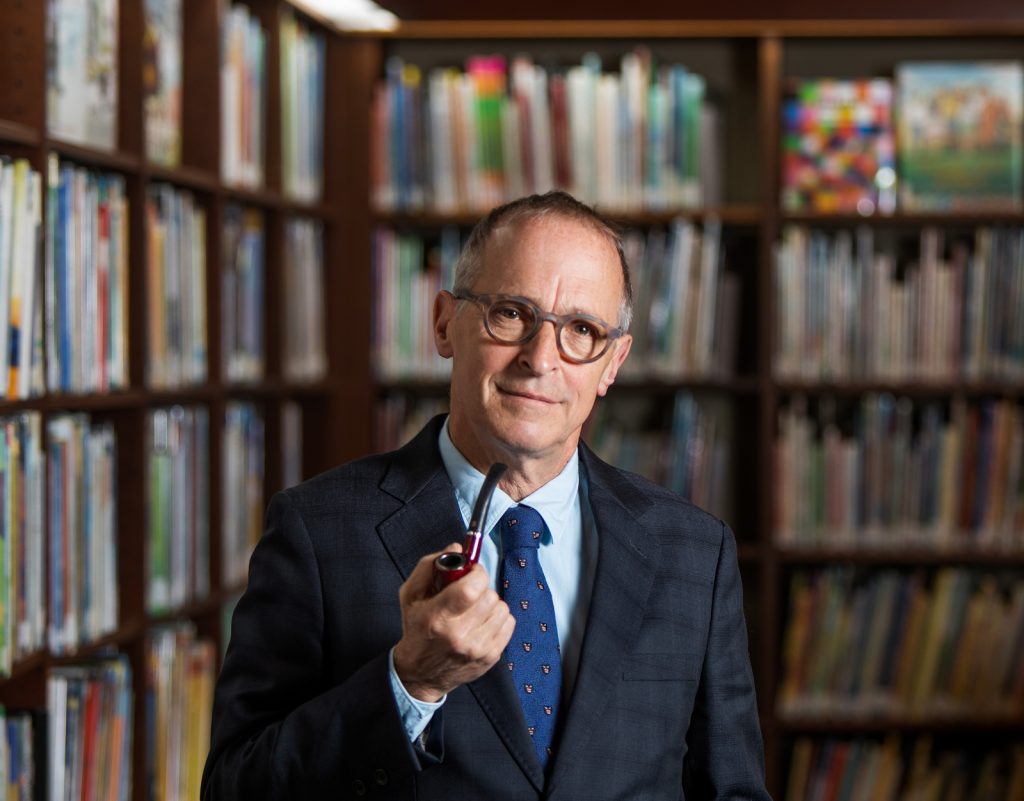

In his new collection of autobiographical essays, Happy-Go-Lucky, best-selling author and humorist David Sedaris writes about topics ranging from guns to teeth to siblings to the pandemic. At the heart of the book is his difficult, unresolved relationship with his father, who died in 2021, and the inevitable change and loss we encounter in life.

Born on December 26, 1956 in Johnson City, New York, and raised in Raleigh, North Carolina, Sedaris dropped out of college and did odd jobs to support himself, including working as an apple picker, an apartment cleaner, and a Christmas elf at Macy’s. In the mid-eighties, he entered the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and began giving readings from his diaries. His life changed in 1992 when he read “SantaLand Diaries,” a comic essay about his elf gig, on NPR’s Morning Edition. Soon he was writing for the New Yorker, Harper’s, GQ, and other magazines and had landed a contract for his first book, Barrel Fever (1994), a collection of essays and short stories.

Sedaris has written thirteen books and is a regular contributor to the New Yorker. He won the Thurber Prize for American Humor in 2001; other honors include Grammy Award nominations for Best Spoken Word Album and Best Comedy Album. Based in West Sussex, England, and New York City, Sedaris tours for the better part of each year and attracts large audiences, sometimes in the thousands. “Eventually,” he says, “people are bound to get tired of me, and I’ll play smaller and smaller theaters, and then they’ll say, ‘There’s nothing smaller than a five-seat theater, Mr. Sedaris.’ Then I’ll just have to retire.”

Late on a Manhattan evening, Sedaris talked with me about letting go, why shopping soothes his soul, and dying without regrets.

–Ann Tashi Slater

In Happy-Go-Lucky, you reflect on growing older and experiencing endings. Do you hold on when something comes to an end? When I decided to quit drinking and quit smoking, those things were just over. I accepted the idea immediately—you know, that’s finished, and I can’t do it anymore. I never had another cigarette and I never had another drink. My boyfriend Hugh and I used to live in Normandy before we bought a house in the south of England. Hugh goes back to Normandy all the time, but even though I loved it there, that’s over. I’ve never gone back. The second I left, I thought, “I’ll just look forward now and start this new life.”

With people, though, it can be harder. When I broke up with the boyfriend I had before Hugh, it took me a long time to let go. I felt like I’d failed. It didn’t matter if we weren’t right together, which was clear.

You also write about seeing your father in a nursing home and thinking, “In the blink of an eye, couldn’t it be me?” How do you feel about aging? There’s nothing good about it except you can ride the bus and the subway for free. In England, anyway. But the worst would be to be old and broke. It would be such an indignity to have to get old with no money. If you have money, then when your youth is gone, your looks are gone, you think, “Well, at least I have that second home.”

I’m at a point now where every other week I’m having to write a sympathy letter because somebody’s parent has died, and I’m about to move into that period where your friends start dying. I already go through my addresses and: dead, dead, dead, dead, dead. As you get older, this person dies, and your sister dies, and then maybe your brother dies, and your best friend dies. It’s a burden of sorrow that you think you can’t carry. But since not everybody dies at once, you find you can carry it. Or you develop dementia or Alzheimer’s, and the burden is taken away from you. You don’t have to remember the people. You don’t even remember having a mother. That’s the bright side.

As you’ve started losing people, do you feel a different quality to your interaction with people you care about, knowing you won’t be together forever? Yes, but I don’t know what to do about it. For example, I can’t think of anybody I say “I love you” to. I’m crazy about my sister, Amy, and we see each other all the time, and we talk on the phone all the time, and we’re inseparable. But I’ve never told her I loved her. If she died, I wouldn’t say “Oh, she didn’t know I loved her. I wish I’d said, ‘I love you.’” It would’ve been a weird moment, pointless.

I went on a trip with my best friend recently, and I did think she could get sick and die. But that doesn’t mean they’re not going to get on your nerves. It’s no help when you’re like, “Will you hurry the fuck up? We’re going to miss this plane!”

It helps, too, that I keep a diary. I don’t care anything about photos, but it’s nice to read about my friends and family in my diary. Every now and then I’ll send people something from the diary to let them know how I feel about them. Some things you can’t send because you’re just bitching about them. But I’ll send sunny reflections on something we did together that they may have forgotten.

You’ve talked about looking at people around you and thinking, “Who’s going to die first? And of what?” I usually think about that when I get news that somebody has died, and they just died. They had an aneurysm or a heart attack in their sleep. And I think, “Well, good for them. Nice.” A clean death; they didn’t have to linger and be in the hospital. They didn’t have to suffer. And I think about my death, when and how it will happen, and I hope I don’t know that I’m going to die that day. I’m often asked what I would have for my last meal. I’ve always thought I’d have the manicotti my mother used to make. And then I saw a cartoon this guy had done on Instagram. He said that for his last meal, he’d have all-you-can-eat breadsticks, so he’d never have to die. You could just keep eating those breadsticks.

“There’s nothing good about old age except you can ride the bus and the subway for free.”

You’ve written movingly about your father’s decline and death, and how the way he changed at the end of his life was surprising to you. My father got dementia and forgot that he was an asshole. For the first time, he was fun to be with. I’m glad I got to see him like that, when he had turned into this little creature who was cheerful and said things you didn’t expect. Part of the change was that he’d always just watched Fox News and conservative talk shows, bathing in that day and night. But the television was complicated in his assisted living facility so he was without it, and, for the first time, he wasn’t filled with rage. The question was: did he change? Or is that who he really was, and it was smothered in layers of rage and frustration that peeled away at the end?

It’s sad that maybe the father you got to see at the end was there all along and you could have had a better relationship. There was never a time when you would just sit around and talk about stuff that interested you both. You could never trust him. He was like a cat: you stroke it and then it turns around and sinks its teeth into you and hisses and claws. When my mother died, I was gutted. I’d never known grief like that. Every day I wondered, “How am I going to get through this day?” When my father died, I didn’t care. I know that sounds harsh, but I’m grateful because it would be awful to have to go through what I experienced with my mother twice.

Is the difference that you had such a difficult relationship with your father compared to with your mother? My mother was a lot of fun. I would call her all the time and she was easy to hang out with. She was nice. She was funny. I got a big kick out of her and she got a big kick out of me. I think about her all the time, and I long for her. If in heaven you were reunited with your loved ones, I’d drop myself out the window right now, thinking, “I can have breakfast with my mother!” We have a terrace and we’re on the twentieth floor. There’s no way I’d survive the fall. But if there’s an afterlife and my father was going to be there, I’d be like, fuck.

In Happy-Go-Lucky, you say you’re finally throwing down the lance you’ve been carrying in battle with your father for the past sixty years because “I am old myself now, and it is so very, very heavy.” Have you really thrown it down? No. I picked it right back up again when my father cut me out of his will. It’s in my hand right now!

“It sounds so false and clichéd, but nothing makes you happier than doing something for somebody else.”

According to bardo wisdom, nonattachment can help us achieve happiness. But as you’ve found in your relationship with your father, it can be hard to let go of grievances. How happy are you? I’m a pretty happy person. I’m not going to bring you down, moaning about stuff or complaining about my health. I don’t have anything to complain about on that level. I go to at least a hundred cities a year on tour, and I read out loud onstage and sign books. That’s me at my best because my happiness is based on doing things for other people. It sounds so false and clichéd, but nothing makes you happier than doing something for somebody else.

Still, I have a hole in myself that I try to fill with material things like houses and paintings and objects and clothes. This doesn’t in the long run make me happy. It’s a deep hole and it’s always been there. I don’t know what it is. When I was young, I would try to fill it by shopping at thrift stores. And now there’s just no stopping me. People think, “Shopping?” But I’m not going to be ashamed of it. I’ve just always loved it.

Why does shopping make you feel you’re filling the hole? Just looking at things and touching things, and the encounters. Today, at Saks, I bought a T-shirt made by this Swiss company. The salesman was busy—the woman in front of me in line wanted something wrapped and there was a customer looking at these expensive wallets, and it was hard for the salesman to turn away from that person and wrap this woman’s present. So I told the salesman, “I can wait.” When he came back, I said, “Are you Danish?” And he said, “No, I’m German.” And then we spoke in German, my pathetic little German, and it was a really nice encounter. The woman who wanted her gift wrapped had just turned to her phone and not engaged him at all. I look at that as such a wasted opportunity. I want the person and me to prove to each other that we’re humans. I want to know that person has a soul and a life, and sometimes I want them to know that about me. I felt a connection with a stranger, and that makes me happy.

The Dalai Lama says, “Not only must you die in the end, but you do not know when the end will come.” You should live in such a way that “even if you did die tonight, you would have no regrets.” Do you have regrets, or do you think you’ll have any? I don’t regret that much. There are people whose feelings I’ve hurt, and I regret that. I apologize, but that doesn’t mean your apology is accepted. And when I was young, I thought, “I’ll just die if I have to spend my life in Raleigh, North Carolina.” I always wanted to live in another country. So I moved to France and then I moved to England, and I’d be happy to move again. I would have a lot of regrets if I’d never done that. I always wanted to see the world. I’ve only been to about forty-seven countries, but it’s a start.

Career-wise, I don’t have regrets. I’ve been offered the opportunity to write TV shows and movies, but I’ve never cared about that, so I wouldn’t regret not doing it. I often tell myself that if my career were taken away, I really enjoyed it while I had it. I’ve never gotten onstage and thought, “The tickets didn’t cost that much. It’s not the end of the world if I don’t give it my all.” I always give it my all. And I always get a thrill out of it.That would be the pity—if you didn’t realize until afterwards that you loved it. And then you’d think, “Damn it, why didn’t I embrace it while I had it?”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.