Years ago, during a long sojourn in India—at the strong suggestion of a Tibetan Buddhist friend, and with the blessing of one of my teachers—I moved my dharma practice to a traditional Indian charnel ground. For several days and nights, surrounded by decaying bodies, feces, blood, and bones, I kept company with countless beggars, several sadhus (Hindu religious ascetics), stray dogs, monkeys, and a handful of Tibetan Buddhists and Bon (the indigenous spiritual tradition of Tibet) practitioners, some of whom shared with me little boxes of chulen (essence pills designed to replace food and replenish energy) and stale dumplings.

I felt apprehensive and leery, reluctant to eat any food or pills offered to me and refusing assistance of any kind, even by those who wanted only to help me walk through the maze of dead bodies without falling. I found myself wanting to discard my dharma paraphernalia, take a long hot shower at a nice hotel, and run to the closest airport to fly back home.

I tried to identify the karmic effects that had propelled me to practice in such a filthy and scary space. Amidst all my fears, mental investigations, and physical discomforts (which made it almost impossible for me to focus on my formal dharma practice), I had the uncanny sense that I was being prepared for a different type of life than the one I had previously been living.

But when I eventually left India to attend to an urgent family matter back home, I quickly resumed the life I had left behind, sitting for practice at a beautiful local dharma center, meeting often with my kind lama (who for years had guided my practice in the United States), returning to my teaching post at the university, and helping with asylum claims at NGO offices in the Mexican border towns of Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez.

Everything, in other words, went back to normal. Or so I thought.

As time went by, I surprised myself by missing my Indian charnel ground, and I often reflected on all the lessons I might have learned there had it not been for the obstacles of my own fear and discomfort. Whenever I talked about my yearning to return to the Indian charnel ground in order to practice, my US lama would smile patiently. Sometimes he responded by saying, “Not good.” At other times he would say, “A charnel ground is any place where you find suffering. So dedicate your dharma practice to the beings that live in the charnel grounds you are inhabiting in the present moment.”

One evening during a visit to Ciudad Juárez, I met a woman named Mercedes at a small café, where she worked as a waitress. Mercedes told me that she had recently tried to cross the border several times without success, but that she was going to try again the following week.

When I told her that I would be returning to California the next day, she asked if I could mail a small box to her son, Emilio, who lived in California at a casa de curación (house of healing). Mercedes explained that Emilio was very sick, which is why she wanted to send an estampita (small image) of El Niño Fidencio, a Mexican miracle healer, as well as some remedios caseros (home remedies). She worried that if she mailed the box herself from Juárez, it might get stolen. I warned her that if my car was searched at the border, the box would probably be confiscated.

Still, Mercedes begged me to take the box to her son and, when I agreed, gave me a big hug and a kiss before saying a prayer to protect me from harm. Then she assured me repeatedly that El Niño Fidencio would look after me.

The following day I crossed the border—with Mercedes’s estampita and remedios in my backpack—without incident. Although I’d planned to FedEx the box to Mercedes’s son in San Diego, when I realized that his address was on my route home, I decided to deliver the gifts in person.

When I arrived at the casa de curación, the front door was open, and I could see three men watching television. To one side of the TV set was an altar crowded with pictures of what looked like family members and Catholic saints. Offerings in front of the pictures included several small glasses of water, a bottle of rum, cigars, and freshly cut flowers. When I told him that I’d come to deliver a box to Emilio, one of the men watching television welcomed me. This man introduced himself as Gonzalo, and when he noticed my interest in the altar, he explained that some of the pictures depicted ancestors belonging to himself, his wife, and the various men who lived with them. The other images were of different saints.

He asked if I was familiar with any of these saints.

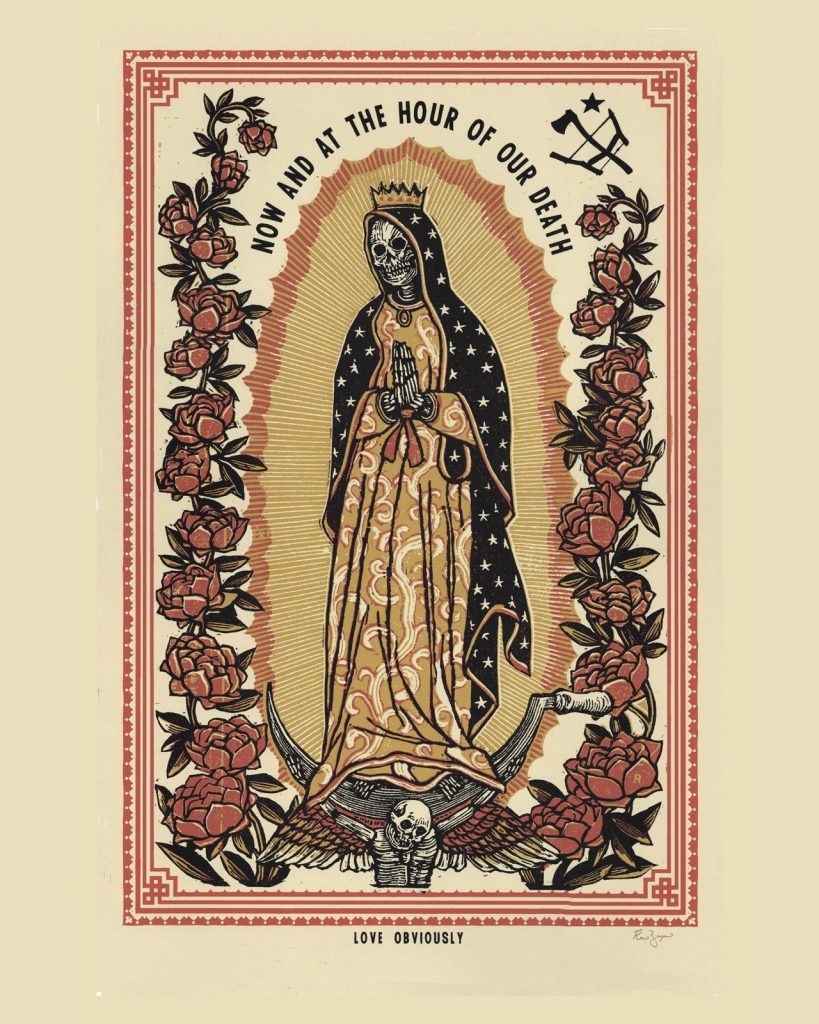

“I think so,” I responded, and proceeded to list la Virgen de Guadalupe, San Judas, San Cipriano, San Diego, and San Santiago (all familiar to me from the altars of the Catholic churches I’d frequented as a child in my native country of Cuba). On a small table tucked away in a corner was a stand-alone picture of a skeletal female figure dressed as a bride and holding a scythe. Her image was surrounded by candles, dried flowers, dollar bills, bones, and other offerings.

Gonzalo smiled and said, “I imagine you do not know Nuestra Señora de la Santa Muerte, Our Lady of the Holy Death.”

“Actually, I do,” I said, feeling somewhat proud.

Gonzalo smiled and explained that La Santa Muerte was the patrona of the house. A little while later, Emilio, Mercedes’s son, came into the room, assisted by Gonzalo’s wife, Azucena, who was a curandera (traditional healer).

Emilio was a tall, frail young man who had some difficulty walking. He had many dark Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions visible on his arms and face. I gave him the box his mother had sent him, and he seemed elated when he saw the contents. He took out the picture of El Niño Fidencio, which came in its own little frame, and put the bag of remedios in his pocket. Azucena put the box away in the drawer of an old desk, on top of which there were even more pictures of Catholic saints and more glasses of water, along with freshly cut flowers, a few cans of beer, and many candles of different colors.

After carefully placing the picture of El Niño Fidencio next to San Diego, Emilio stayed leaning near the altar, as Azucena asked me all sorts of questions. But before I had a chance to answer any of them, she said, “This is a casa de curación, and I am a curandera. The men here have AIDS. I am telling you this because I can tell you can be trusted.”

She paused expectantly, but when I didn’t respond, she continued, “Some other time, I will tell you why you are here.”

I felt she was trying to elicit some reaction from me, though exactly what kind I couldn’t guess. Suddenly I found myself wanting to leave. I wanted to go home, but instead I stayed at la casa de curación for several hours that day, and I would return many more times during the course of the next year.

La casa de curación was home to six men from Mexico and Central America who had full-blown AIDS, as well as to Gonzalo and Azucena, who were both trained as certified nursing assistants. The home was supported by both private donations and donations from an NGO. The nearby medical center provided medical treatment for the men, although Gonzalo confided that these allopathic treatments were supplemented by many potions and Mexican foods, as well as by prayers, limpias (cleansings), and other rituals.

Before coming to the United States, Azucena had been trained as a curandera by her grandmother in Mexico, and Gonzalo had studied with several healers in his home country to become a yerbero (traditional herbalist). A sobador (traditional Mexican masseuse) visited the casa often to treat the residents as well as Gonzalo and Azucena. Native herbs were grown in the casa’s garden and also purchased from a nearby botánica (traditional botanical store) where incense, oils, herbs, candles, and other ritual items were also obtained. Azucena, unlike her husband, was documented, and would occasionally cross the U.S.-Mexico border to obtain remedios unavailable in the United States.

At Azucena’s request—and with Emilio’s consent—I began to visit la casa de curación once a week, staying for a couple of hours each time. During my visits, Emilio and I talked about his AIDS disease, his diabetes, and his severe kidney problems. He told me that he knew he was going to die soon and was preparing for his own death. Azucena encouraged him in these preparations and asked him to invoke La Santa Muerte more frequently.

Though I didn’t say so openly, I considered this skeletal saint (who at the time was increasingly associated with drug users and cartels) not worth invoking. Emilio tried to dissuade me from thinking negatively about his patrona, saying that La Santa Muerte was nonjudgmental and tried to help everyone—saints and sinners alike—without preference. For Emilio and Azucena, the saint’s supreme neutrality reflected the fact that Death treats everyone equally.

Eventually, Mercedes, Emilio’s mother, crossed into the United States to live near her son. I began to look forward to my visits to la casa de curación, where, in addition to participating in interesting conversations, I would also occasionally get a free massage from the sobador. Sometimes Azucena would interrupt my conversations with Emilio to serve us strong-tasting juices made with special herbs meant to cleanse our energy.

Emilio and I regularly talked about religion, La Santa Muerte, El Niño Fidencio, death, rebirth, and healing work. Emilio was especially interested in Buddhism, which he had first learned about while studying at San Diego State University, before he’d been diagnosed with AIDS. Several months went by in this way. But then Emilio began to get sicker. Gonzalo had to take him to the emergency room a couple of times.

After one of those hospital visits, Emilio asked me if there was a Buddhist practice or ritual that we could do together. I asked what he hoped to accomplish with such a ritual, assuming that he wanted some kind of help with his health. But he explained that he left everything to do with his health to El Niño Fidencio and La Santa Muerte.

“I want to learn about Buddhism because Buddhists are supposed to try to help others all the time, and I want to do that,” he said.

“Why?” I asked.

“La Santa Muerte wants us to use all means to help ourselves and others. I can learn a new way from you,” he answered.

So I taught Emilio about tonglen, the “Giving and Taking” practice, which was my main dharma practice at the time. Soon after that, we began practicing together.

“Dedicate your dharma practice to the beings that live in the charnel grounds you are inhabiting in the present moment.”

We also had many discussions about ancestors and prophecies. Emilio shared various prophecies from his Mesoamerican culture, and I shared the Buddhist teachings about the Era of the Five Degenerations. We discussed our concern for the beings that Emilio called “restless ancestors” and that I called “beings caught between the bardos (in-between states) of death and rebirth.”

Mercedes, Azucena, Gonzalo, and one of the men living in la casa sometimes joined in these discussions. Although we disputed a few minor points, we all agreed on the need to cultivate compassion for all living beings, including animals. The residents of la casa also insisted on including their beloved plants on the list of things that deserve compassion, for they believed that plants are very much alive and aware.

We also talked about self-cherishing as the main source of suffering, and how tonglen practice can be helpful in reducing the tendency to cling to an “I.” The others related especially to my comments regarding the need to avoid thinking of things as “mine.” We all concurred that everything belongs to everybody—and, in the end, to nobody, as La Santa Muerte teaches.

Eventually, all the members of la casa de curación, Mercedes, and the sobador joined Emilio and me in the practice of tonglen.

Tonglen is considered a very powerful and difficult practice in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, and it is recommended that we engage in this practice only after receiving careful instructions from an experienced tonglen practitioner.

We breathe in the suffering of all beings. We breathe in the suffering of other living beings and use that perception to destroy our self-cherishing mind, which is the source of all our own suffering. We also breathe out everything we cherish, including our body, possessions, merit, and happiness. We send them toward other living beings for their benefit.

Although it is recommended that we do this practice on a regular basis, it is said that it is particularly powerful to do tonglen when we are facing a serious problem, because we can use our pain to develop compassion as well as experience our suffering on behalf of all sentient beings. Some believe that tonglen practice can heal the practitioner from illnesses.

I initially introduced the image of black smoke to represent the suffering we were breathing in, but the others in the group resisted this idea, and Emilio asked if it would be all right to imagine some of the suffering coming in the form of smoke of different colors, including white, because suffering comes in many colors. Likewise, the group wanted to visualize the light of our exhalations in a variety of colors.

We practiced various forms of tonglen together once a week for about two months. Every week, through our breath, we took in suffering from ourselves, from all types of beings alive at the time, the restless dead, and the children yet to be born into these catastrophic times. Through our breath, we also sent offerings to all beings.

At the end of these practice sessions, Azucena and Emilio said prayers to

La Santa Muerte, thanking her for encouraging them to think about the well-being of everyone without exception and to keep the awareness that we were all equal because all of us are destined to die.

As Emilio’s health continued to deteriorate, he started to beg his mother to take him back to Mexico, where he said he wanted to die. Mercedes resisted, hoping that his doctors could arrange a kidney transplant that might extend his life. She also hoped that the treatments Emilio was receiving at the San Diego hospital and at la casa would prolong his time on this earth. But in the end, she relented and organized what she hoped would be a quick trip back home.

Azucena, Gonzalo, and I began to plan a ceremony to say goodbye to Emilio. Gonzalo hurriedly began to build two more altars to both honor Emilio and those he believed were now Emilio’s two most important spiritual patrons as he drew closer to death: La Santa Muerte and Buddha Amitabha, whose Pure Land Emilio seemed to have developed a strong attraction for after he heard me recite the Prayer to be Reborn in Dewachen (Amitabha’s Pure Land). Both altars faced west because it is said that La Santa Muerte always reminds her devotees that her true home is in the land of the dead, which is in the West, and because Gonzalo remembered Emilio mentioning that Amitabha was the Buddha of the Western Paradise.

At midnight, on a cold evening a week after the feast of the Days of the Dead, we held a goodbye ceremony for Emilio. It was attended by more than one hundred people, mostly relatives and friends of the residents of la casa de curación. Some were also devotees of El Niño Fidencio or La Santa Muerte. The ceremony was conducted by Azucena, who appeared to be in a trance, and by my Tibetan lama, who joined us for the occasion.

Throughout the night, I helped Emilio to stand up as well as kneel at different moments in the ceremony. Azucena invoked and prayed to La Santa Muerte on his behalf, and my lama recited the Prayer to be Reborn in Dewachen. At the end of the ceremony, Azucena burned incense, my lama bestowed blessings on all seen and unseen beings who were present that night, and Gonzalo passed around several trays of plantas sacramentales (sacramental plants), donated by the owner of the local botánica.

Clutching the picture of El Niño Fidencio that I had delivered to him on behalf of his mother, Emilio approached the altars and bowed several times, then placed dried flowers on La Santa Muerte’s altar and fresh flowers on Amitabha’s. He hugged me and handed me the box I had brought him. Inside were the picture of El Niño Fidencio, an image of La Santa Muerte, and some remedios.

Mercedes and Emilio left for Mexico the next day. Not long afterward, Mercedes called me to say that Emilio had died. As soon as I received the news, I called my lama so that he could perform Phowa (a Tibetan Buddhist practice of ejection of consciousness at the time of death). I also initiated a forty-nine-day ritual for the dead based on the Bardo Thodol (The Tibetan Book of the Dead). Then I called Azucena to let her know about Emilio’s passing, which Mercedes said had been peaceful.

She whispered a brief prayer for our friend, then asked me, “Now do you know why you came to my house?”

I told her I did.

Inever returned physically to la casa de curación, but I remained in touch with Azucena and Gonzalo for a couple of years, until they, too, returned to Mexico, where they hoped Mercedes and her new husband would join them in helping people heal from illness and become friends with death before their own dying processes began. When I last talked to her, Azucena promised that she and Gonzalo would both keep me in their prayers to El Niño Fidencio and, especially, to La Santa Muerte.

In my mind, I often return to my Indian charnel ground days as well as to the times I spent at la casa de curación, where I began to learn to accept the inescapable—not try to evade it—and to work with whatever presents itself. These days, I am privileged to assist mostly (though not exclusively) dying Latinx men and women who may live in community group homes, squatter houses, shelters, cars, or even in the streets on both sides of the border. I visit and serve these people as a friend, a professional helper, a dharma practitioner, and, sometimes, simply as an old immigrant who, herself, is always on the lookout for boxes of spiritual inspiration and remedios.

Adapted from “In the Charnel Ground of a Dying Latinx Man,” an essay that appeared in the collection Refuge in the Storm: Buddhist Voices in Crisis Care, edited by Nathaniel Jishin Michon and published by Nbuddhism death crisis care lantinxorth Atlantic Books, copyright © 2023. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.