Right speech is one of the practices of the noble eightfold path introduced by the Buddha in his first sermon. The other practices are right view, right intention, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. Together, they form the way to end suffering and live in harmony with all beings. Along with the precepts, they serve as a moral compass by pointing us in the direction of not causing harm.

During the Buddha’s lifetime, right speech was understood in the context of an oral society, which is why the opening line of many ancient Buddhist texts is, “Thus have I heard.” In oral societies, communication is characterized by immediacy in that the spoken word can only be heard. If you didn’t hear what was said firsthand, then you heard it from others who memorized and transmitted it. Of course, as information gets passed on from one person to another, it can take on a life of its own.

In What the Buddha Taught, Walpola Rahula provides an account of what was remembered and eventually written down from the Buddha’s teachings. The Buddha said, “Right speech means abstention: 1) from telling lies; 2) from backbiting and slander and talk that may bring about hatred, enmity, disunity, and disharmony among individuals or groups of people; 3) from harsh, rude, impolite, malicious, and abusive language; and 4) from idle, useless, and foolish babble and gossip.”

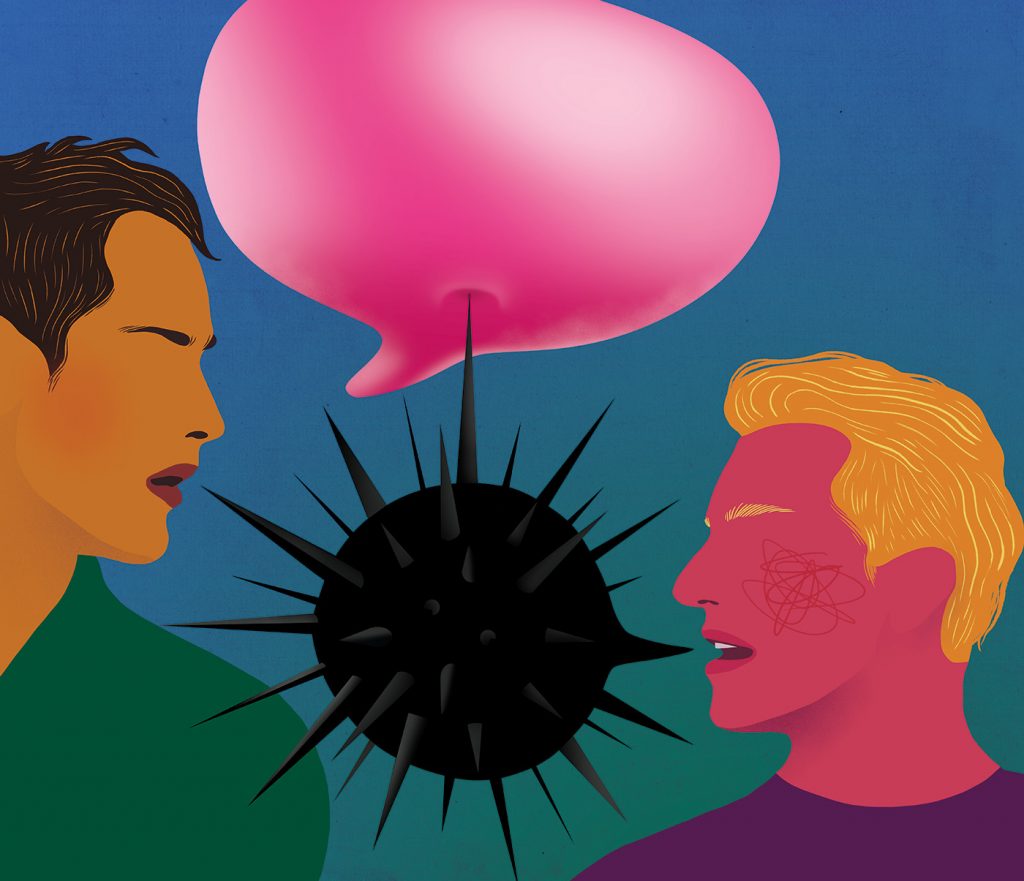

We can readily see how each of these kinds of speech can be expressed through the spoken word. We can also recognize how distracting and toxic they would be in the context of living within a monastic community, where people live, work, and practice in close proximity. The same applies to practicing in a broader sangha, which includes doing zazen together and participating in social activities.

And yet what constitutes speech that does not cause harm is not entirely clear-cut. For example, lying may be appropriate in situations where keeping confidentiality or withholding information results in the least amount of harm. There are also situations with individuals where strong or harsh language is necessary to get a point across. Sometimes, idle chatter about relatively trivial topics, like the weather, food, or a Netflix show, can be helpful in building social connections.

Because there is no fixed set of rules for what constitutes right speech in contrast to “wrong speech,” the word “right” shouldn’t be taken as a moral commandment. If you say or do something “wrong,” it’s not as if there’s some Zen Buddhist god who will send you straight to hell or inform you that you’re no longer eligible to continue on this path.

Instead, we learn what is most skillful and compassionate through practice. We make mistakes and cause harm, and in the process, we learn how to do better next time—which requires us to own up to our shortcomings. Our speech has the potential to foster mutually supportive and nurturing relationships, but it can also advance our self-interest and sow division. We won’t always get it right. There will be blunders and awkward moments. At times, we may overreact and become defensive or self-protective. We may cause harm to ourselves and others and to our relationships. This can happen even when we have the best of intentions, even when we’re trying to be mindful, skillful, and kind. Each of us is on the path, finding our way.

Often, our missteps are a product of conditioning. We’re conditioned to see ourselves as separate and in opposition to others. Skillful and compassionate speech and action arise from the awareness that we are not separate. That is why maintaining a regular sitting practice is so important, more so than going to sesshin. When our practice is consistent, we’re more likely to maintain a stabilized mind and not be swayed by passing mental and emotional states. We’re in a better position to be present and intuit what’s needed in the moment—what needs to be said and how.

In Zen, morality is dynamic and fluid. Again, there’s no line to be drawn on what constitutes “right” and “wrong.” This is a really important point. What kindness or compassion looks like in practice is not necessarily what we might imagine it to be. Often, people think that compassion must involve being outwardly kind, forgiving, gracious, generous, and sympathetic. Yes, in appearance it can look like these qualities. But sometimes compassion looks fierce, as in wielding a sword.

We make mistakes and cause harm, and in the process, we learn how to do better next time

If we always give in to others, habitually yielding to their preferences because we don’t want to cause a stir or arouse conflict—in a codependent kind of way—are we really helping them? Are we really seeing someone’s true nature if we go out of our way to accommodate and encourage their self-partiality? Is that what compassion looks like?

There is a tendency to see conflict as something to be avoided. But when we head straight into conflict in a skillful way, it transforms into an opportunity to close the gap. It can be a selfless act of love to tell someone that their behavior is misguided or harmful, and to urge them to make a course correction or get help. Right speech is not about making people smile or feel good about themselves. Nor is it about avoiding uncomfortable feelings or difficult conversations. It’s about the authenticity that arises out of nonduality.

How often are we inauthentic in our interactions and relationships with others? We want people to like us. We put time and mental energy into making a good impression. We want people to look up to us. We want to be in control of the image or persona that we’re putting out to the world. To be authentic is not to be worried or constrained by what others may think or say about you.

We can see the practice of right speech as fundamental to authenticity in that it is through communication—speaking, writing, nonverbal gestures, listening—that we conduct much of our life. This includes not just our interactions in the context of family, work, relationships, and so on but all the ways we engage with and navigate a complex social world. How can we communicate in ways that are not driven by self-concern and instead create openings in service to our own liberation and others’? A good example of a situation that can lead to such an opening is what happens when you’re in a conversation and there’s a micro-aggression—whether it comes out of your mouth or another’s, or if you’re on the receiving end.

Microaggressions are subtle, commonplace, and often unintentional expressions of prejudice. Rather than some blatantly hateful racist, sexist, or homo- or transphobic remark, they take the form of casual, seemingly benign comments or questions that are a product of unconscious bias. For the person on the receiving end, it’s the frequency and repetitive exposure that causes the harm. It’s like being told repeatedly, across a lifetime, that you’re “Other.”

A classic example of a microaggression is the question, “Where are you from?” In everyday interactions, it’s a question that many of us naturally want to ask when we meet someone new. It seems totally harmless. What’s wrong with asking someone where they’re from or where they grew up? It’s information that helps us to get to know them and make a connection.

Yet, depending on one’s life experience, it can mean a lot more than that. Instead of making a connection, it can result in hurtful feelings and fuel separation. And it’s not entirely clear-cut or predictable because how it is interpreted depends upon the context. That said, we do live in a society with a long history of racial violence and white privilege. So what might happen when a white person approaches someone they’ve never met before, who happens to be the only person of color in the room, and asks, “Where are you from?”

The way it gets interpreted and its impact can go way beyond what seems like an ordinary question. For the person on the receiving end, it’s as if you’re being seen only as a skin color, not as a person with a personality, interests, and talents. In a word, racialized. The impact and the resulting separation that this microaggression causes can really undermine one’s sense of trust and belonging.

So what’s the remedy? First, we can do our best to educate ourselves about unconscious bias and how it can be manifested in our thoughts and speech. We all have biases of one kind or another because of our social conditioning. You can also show some care and support when you witness it happening to a friend, a coworker, a family member, or a sangha member. Take them aside and check in with them.

Of course, you can also touch base with the person who made the potentially harmful remark, as they’re probably not aware of how it came across. If you’re the one receiving that feedback, avoid getting defensive. Be open to receiving it. Say “thank you.” Recognize that it’s a product of conditioning, not that you’re a horrible person.

Over 2,500 years ago, when the Buddha spoke of the practice of right speech, he recognized that speech has the potential to be nurturing or to cause harm. Here’s what he said further about abstaining from speech that fuels separation, as recounted by Rahula: “When one abstains from . . . wrong and harmful speech, one naturally has to speak the truth, has to use words that are friendly and benevolent, pleasant and gentle, meaningful and useful.” But this isn’t about donning a fake smile or manufacturing pleasantness, which would be inauthentic. Rather, it’s about maintaining equanimity, a mind that is undisturbed.

Inner silence creates a space for recognizing the true nature that we equally share.

The Buddha also says, “One should not speak carelessly: Speech should be at the right time and place. If one cannot say something useful, one should keep ‘noble silence.’ ” When I was a child, my parents would tell me, “If you don’t have anything nice to say, keep your mouth shut.” At the time, that pretty much meant: Suck it up. Bite your lip. Hold it inside. Silence is golden. But if we do this, what often happens is that the feelings we hold inside come out in other ways, such as passive aggression, sarcasm, or the cold-shoulder treatment. And, as the pot simmers, it may eventually boil over.

Keeping a noble silence is altogether different. It’s not about holding back but letting go. And it doesn’t necessarily require one to be silent, as in not saying a word. What makes silence “noble” is inner silence. Inner silence involves being present and attentive to the moment and the people that you’re with, even when it feels uncomfortable or unpleasant. Noble silence closes the gap between self and other.

We create an opening when we approach our interactions with inner silence and an undisturbed mind—which is made possible through our zazen. It’s an opening for seeing clearly. Not seeing through the filter of our feelings, thoughts, or memories of the past, but seeing things as they are. Inner silence creates a space for recognizing the true nature that we equally share. In the words of Rumi, “Silence is the language of the heart.”

♦

Originally published in the Spring 2025 issue of Rochester Zen Center’s Zen Bow.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.