I grew up in Taiwan in the mid-seventies. Most of my free time was spent in the kitchen, not cooking, but serving as a (fat) guinea pig for the family chef. At that time, we knew a number of families who had their own chefs. Most of these families were Kuomintang elite, wealthy and influential through their association with the ruling party, who had fled China with the Nationalists in the late forties and who had been residing in Taiwan comfortably, if not luxuriously, ever since. The families we knew traded chefs periodically in order to enjoy a change of cuisine. Whenever a new chef would arrive in our home, he would always bring two things: a fine lacquer box containing his well-cared-for and well-used cooking implements, and a collection of his own secret sauces. Since I was already famous among the chefs of Taipei as what we call in Chinese a “greedy mouth,” they always used me to find out whether their sauces and dishes had the right amount of spice or salt for my family.

Sometimes I would find myself in a kind of reverie in that kitchen, lulled by the rhythmic sound of chopping and the whistle of the kettle into fantasizing that I was riding on the train to my grandmother’s house in Puli. But my most vivid memories from that time are the stories told to me by the chefs of their heroic deeds back in mainland China. Their battle epics were poetic and colorful, nurtured and decorated through years of telling, and accompanied by the sounds of their powerful and skillful chopping. It was as though they were hacking away at their Communist enemies while preparing our food. Once served, however, the aromatic meal would silently cast its spell of comfort and intimacy.

As a child I also spent many summers training under an elderly Ch’an monk who taught me Buddhism—not through lectures, but through allowing me to help him with everyday monastic chores: cleaning, cooking, gardening, sitting in silence. He sensitized me to Buddhist ideals of awareness, compassion, and the value of interpersonal exchange and cooperation in fostering personal growth.

My artistic language is not primarily that of visual images, shapes, or words, but rather of awareness, internal experience, and interaction. My work raises questions about what art is and can be, about how it changes our experience not only of the present, but of our interpretation of past and future experience. Can art be the attentive performance of simple actions? Can art be the manipulation of attention itself, the bringing of greater awareness to ordinary things, thereby transforming our life and our perceptions? Such questions arise naturally in a Buddhist context.

The Buddhist influence on my work is not limited to my interest in nurturing interactions (compassion), but is also evident in my focus on process as opposed to content, on the changing world of feelings and ideas as opposed to that of the (seemingly) more permanent world of objects. My works are more temporal than spatial, like music and dance, but they are primarily interpersonal, relying more on the movements of mind and heart than on those of the body or instruments. My spaces are temporary and minimal, my artistic products the subtle influences of interpersonal encounter on spiritual growth.

In addressing these questions, all my works have both an inner and outer form. The inner forms are loosely planned, somewhat ritualized interactions that seek to clarify and explore certain issues. The outer forms are the spaces and objects needed to create the proper situation for those interactions.

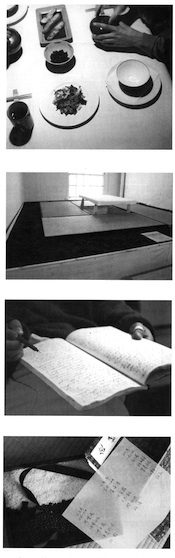

Image 3: Dining space in the artist’s studio. Courtesy Lee Mingwei.

Image 4: Journal given to participants. Courtesy Lee Mingwei.

Image 5: Wooden box, containing a layer of black beans and rice, menu on vellum, and journal, given to participants at end of process. Courtesy Lee Mingwei.

The themes of this particular project are personal reflection, self-disclosure, and interpersonal nurturance. First I meet with potential participants to make sure they understand the project, and that they are willing to disclose potentially intimate written information, at least anonymously, to strangers. The participant is then invited to a private meal in my studio. I prepare and serve a beautiful Asian meal especially for my guest, with the intention that food and environment will be catalysts for a meaningful, self-exploring, mutually growthful dialogue. I attempt, in other words, to evoke the social, psychological, and spiritual dimensions within the biological act of eating, and to create an atmosphere of sincerity, trust and self-disclosure that sets the tone for the rest of the project.

At the end of the meal, I give the participant a blank book that I have made especially for him or her. I explain that this book is to function as a container in which the participant might continue documenting the sort of deep ideas, feelings, and impressions that were evoked during the shared meal. By associating the book with the meal experience, I hope that it will act as a stimulus to continued deeper reflection on the part of the participant.

The project will terminate in the spring of 1997, when I will exhibit the books in a gallery setting for several weeks. Visitors to the gallery will enter into an atmosphere of respectful quiet and attention to the materials presented. They may sit and read the participants’ journals while I serve them tea and light refreshment. I will then ask them to share their thoughts about the journals’ contents, about the project, and about themselves, thus recreating the atmosphere in which the journals were born. Visitors are then invited to become participants in this phase of the project by recording their own thoughts and feelings in another blank book that I’ve made for the occasion.

The participants’ sharing of thoughts and feelings with strangers is a gesture of trust and honesty that begins with one person in a private setting, and grows to embrace an anonymous public who might benefit from being allowed to look into the hearts and minds of those immediately around them. Having received food, dialogue, and a book from the artist, the participants now in turn offer nurturance to others by sharing their interior lives, and inviting readers to explore their own.

At the end of the project, participants will be given a wooden box containing a layer of black beans and rice (reminiscent of the dining space, which was surrounded by a border of black beans, and at which rice was served), on top of which rests the menu for their first meal, handwritten on vellum. On top of that is their journal. The gift box is intended both as a reminder of the process and as an encouragement to further self-exploration and disclosure.

Thus I weave food, gifts, and discussion into a special form of nurturance, a form rooted in my Buddhist training and in the many hours spent in the kitchen of my childhood.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.