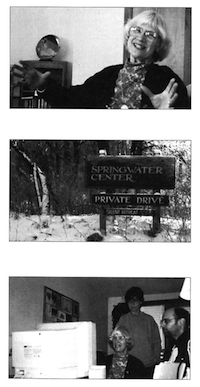

Toni Packer heads the Springwater Center for Meditative Inquiry and Retreats (located outside Rochester, New York), which she founded in 1981. During the previous thirteen years, she was a student of Roshi Philip Kapleau and served as a resident teacher and director of the Rochester Zen Center. Her rejection of the ritualized formalities of Zen, coupled with her studies of Krishnamurti’s teachings makes Springwater a singular experiment in bare-boned awakening, with few of the rituals, accouterments, symbols, or formal practices that traditionally attend this quest.

Born in 1927, Ms. Packer grew up in Nazi Germany as the daughter of two scientists. Her mother was Jewish, but the family was protected by her father’s prestigious career. After the war, the family emigrated to Switzerland, where Toni met her American husband, Kyle Packer. The couple came to the United States in 1951 and settled near Buffalo.

Today, Ms. Packer spends half the year in residence at Springwater and several months a year leading retreats in California and in Western and Eastern Europe. She is the author of The Work of This Moment and The Light of Discovery (both published by Tuttle). This interview was conducted by Helen Tworkov on the first day of spring, 1996, at the Springwater Center.

Tricycle: So often you speak of clear seeing and just listening. What makes this distinct from “regular” seeing and listening?

Packer: Have you ever listened to breathing without knowing what it is? Without thinking about where it comes from or where it goes? This is an innocent listening—unburdened, unhindered by knowledge or by judgment, such as “My breathing is too shallow”; innocent listening is no right breathing, no wrong breathing. What is there when I don’t come to listening with preconceptions, but rather start freshly?

Tricycle: It sounds so easy. Why is it met with so much resistance?

Packer: We are so used to imagining our world and creating ourselves and each other in our thoughts, in our imagination and fantasies. We do not want to be awakened from this dream because it has such power.

Tricycle: Power because we are always the star of our own dreams?

Packer: Or the victim.

Tricycle: You mean we get entrapped in the dream by being the star, which makes us a victim?

Packer: Yes. But also victim in the sense of “Why me?” People are so attached to the sad story of their lives.

Tricycle: So attached that they can’t let go?

Packer: If one is desperate enough, or choiceless enough, one can’t do other than stay with this moment, even if it is filled with anxiety and pain, the uncertainty of not knowing. The scary thing is what we know about not knowing. There’s nothing scary about truly not knowing, because at that moment the mind is quiet.

Tricycle: Is there a process by which we can let go of the story?

Packer: I don’t know about process, but what is it to be with this resistance you mentioned without attacking it, without trying to overcome it, without knowing it—allowing it to be there in full view, unfolding in full presence: feeling the body harden, the stomach tighten? Because there is presence every moment, it is possible to be with resistance without looking beyond it, without knowing it. We believe it’s dangerous to be fully present; we’re afraid to disappear, to lose all we hold dear. But these are all false assumptions that can be put to the test. There is nothing to know here, nothing to fear, nothing to resist. But of course the intellect wants to come in and take over. That’s its function. If we see that as it takes place, then there is no problem.

Tricycle: In much of your work we see a radical departure from the formal Zen mode in which you originally trained, especially in the absence of the traditional forms. Yet one of the most overt characteristics of Zen, historically, is its insistence on the absolute view. And in much of your work, there seems to be a similar urgency to grasp the absolute view.

Packer: Because you cannot truly see the conditioning without that.

Tricycle: The absolute “experience” of anxiety lies in staying with the anxiety and seeing it?

Packer: Seeing it completely. Wordlessly, the whole thing. Seeing our moment-to-moment automatic conditioned reactions is crucial. Without that we will just continue the mess we are creating in our world, in our loveless relationships. Without clarity, the self-pitying or self-aggrandizing soliloquy takes up all the space; then there is just this little stage for the actor, the victim, the hero, the star. If that isn’t seen, self-pitying and self-promoting proceeds and makes oneself and others miserable.

Tricycle: You present this with no process, no effort. But for most of us, discursive thought dies hard. It doesn’t often just release into spontaneous awakening.

Packer: What are these “discursive thoughts” you want to “release into spontaneous awakening”? Right this moment, what is thought saying? Something like, “I’m afraid of being here”? “I’m not listening well enough”? Or, “I don’t like the sound of that chain saw, I prefer the song of the birds”? Can discursive thoughts be heard as they arise in open listening? No need to judge, no need to control. Simple awareness of what’s arising makes it possible to let go. I think that evolves very naturally.

Tricycle: If it evolves so naturally why do so many of us struggle with it?

Packer: Nature is effortless even though it does incredible things. We try to make an effort to make no effort. But then every once in a while, wonder of wonders, there is an instant where there is no effort. It is all happening on its own. Then the effort arises to capture the moment of effortlessness, or to remember it.

Tricycle: And so your “effort” is to get us unhooked, derailed from that track of effort?

Packer: I truly have no method. There is no formula for saying “You should or should not do this or that.” Awareness this moment reveals what needs to be done or left alone.

Tricycle: All those years you studied in a formal Zen context, did the effort never pay off?

Packer: It does pay off, because after all this effort somebody says, “No effort is necessary.” Then suddenly all the energy of effort is available this moment.

Tricycle: And your Zen experience?

Packer: I appreciated sesshin [one-week retreat] tremendously, and I did put in a tremendous amount of effort. I was just the right person for Zen: very ambitious, wanting to excel. I wanted to be a model to others, to sit late into the night, longer than anybody else, to be the best student. I loved it. Earlier in my life I wanted to be an actress, a performer.

Tricycle: So the whole Zen thing was a big performance?

Packer: There is a lot of it in there—the beauty of these flowing robes.

Tricycle: But didn’t it inspire you?

Packer: Of course it inspired me, but what all goes into the ice cream of inspiration? One has to be very scientific, if you will, and not romantic, because it is amazing if you begin to watch what arouses inspirational energy. The rituals and ceremonies we participate in arouse enormous energies and we believe we are touched by the holy spirit. But maybe it’s just thoughts and melodies and movements and all the chemicals circulating throughout this body-mind. There is nothing wrong with that. But awareness reveals something beyond all of that pure being. Not to renounce anything. Not that I should renounce this so that I get to pure being.

Tricycle: Is it really your experience that Zen training cannot bring you to that?

Packer: Nothing can bring me to it, it is here. How this bursts upon one, nobody knows.

Tricycle: And you are saying that there is no methodology?

Packer: No, not that I know of, and yet we engage in it. I engaged in searching, reading this book and that book. First there was psychology, then Joseph Campbell, then Alan Watts, struggling with trying to find the meaning of “What is the meaning of this meaningless life?” Then going to Zen training and enjoying tremendously the energy that manifested as awareness. The falling away of problems in this awareness and presence. The falling away of the Jewish problem, which didn’t bother me after that. I had made a real identity out of this suffering as a half-Jewish person. In Germany, I had a tremendous need to tell anybody who wanted or didn’t want to hear about it. I played the role of the victim. Being somebody through my suffering.

Of course, we engage in what we can’t help engaging in; but to say that this is the cause of waking up—how can you say that? Waking up happens on its own. Yet you ask, “Everything that led up to it: did that have a purpose, did it have a function?” I don’t know. We engaged in it. We did it. It happened.

Tricycle: Are you so convinced that the methodology of effort can’t work for anybody?

Packer: I don’t need to solve this question. The beauty is that if you don’t direct people and involve them in methods and programs, somehow or other each organism seems to know what it needs to do at a point in time. Here some people go for walks during retreat, or occasionally go for pizza. Other people rarely leave the sitting room.

Tricycle: There are so many curious paradoxes here. For example, in the Zen texts, we read of disciples being told to “Be the fear. Be the anxiety.” Not separating from it. Not thinking about it. Which stops the mind stream, undercuts discursive thinking. For many Westerners, this was too harsh. They wanted some psychological space, especially with the teacher. And many of the Western teachers have complied, especially by using private interview time to delve into all kinds of personal and psychological situations. And while you may provide the most radical alternative to Zen style, when you ask, “Can you be with the fear?” your voice may be very nonthreatening, but in terms of one’s storyline, you don’t cut any more slack.

Packer: Unless it is clearly seen that the storyline about me perpetuates fear and pain, it will automatically keep on going. Discursive thinking is not separate from what is here, but its release cannot come from prohibition, or practice, or admonition. As long as I am thinking about it I am circumnavigating it. I am not really with it, seeing it unconditionally. My recollection is that in the Zen practice I was exposed to something was often done now for the sake of something else in the future.

Tricycle: Even though we say it is now.

Packer: Yes. “Work hard now for future enlightenment.” I remember that after the teacher passed the koan mu on to me, he pointed to a corner of his mat and said: “OK, now you are here and no longer there, [pointing to the floor] but you still have to get over there [pointing to the other corner] which is full enlightenment.” I thought to myself, “Oh my goodness, now I have to get someplace again. I have to go somewhere from here.” Whereas with this work, there is only now. There is no other time and place. Only now, and now, and now.

Tricycle: The one association that everyone has with Krishnamurti is that he said he was not a teacher. In a similar way you have become known as “Toni Packer who is not a teacher.” It seems that this “not a teacher” can set up as many preconceptions and expectations as “Packer is a teacher.” It seems that the mind is going to grasp on to any description, “not teacher” or “teacher,” and sometimes it feels like they are the same thing. There is “teacher,” there is “not teacher,” there is form, no form, cushion, no cushion; yet you have continued to speak of “not form, not teacher, not authority.”

Packer: In recent years, I have almost stopped talking about not being a teacher. It was too confusing for many people. I point to our deep-seated urges to create authority in ourselves and in others. I invite all of us to bring this to light in our moment-to-moment living. And not just to take what I say for the truth to be believed or parroted. But when I do say that I’m not a teacher, I mean something very simple: I do not have that teacher image of myself. It dropped away quietly. Once I had that image and it was very powerful. People were prostrating before me as their teacher, opening up an aisle in the crowded hall to let the teacher exit first. It is tremendously destructive, that image of a teacher. In reading and listening to Krishnamurti veils dropped from my eyes. I realized that nobody around me really looked at these roles we were all playing because we were all so attached to them.

Maybe not everybody just milks the image for themselves. Some people have an amazing congenital modesty, and others need to pump themselves up. But see, to work with others, one has to be there in all simplicity, in a state of no trip, in order to see other people’s trips.

Tricycle: And what do you do with the projections of your students?

Packer: I let people do what they need to. This work may illuminate something: any image gets in the way of simply being together.

Tricycle: You say about yourself that you are not an authority. But you have a very authoritative voice. And people come to see you because they feel, or they project, or they expect you to know something that they too would like to know.

Packer: There is a difference between being authoritative and being authoritarian. I’m not denying the strong energy that moves me to express in talks and meetings what is seen to be so. If you call that “authority,” so be it. My warning about following me as an authority means: “don’t stop looking and thinking because of what I say. Don’t take my word for the truth but test it out for yourself.”

Tricycle: Does the attraction to and rejection of authority relate to growing up in Nazi Germany?

Packer: Yes, in part. But you don’t need Nazi Germany in your background to see the abuse of authority. Germany is all around us. Surely what drove me to this whole spiritual inquiry was the utter meaninglessness and cruelty and catastrophe that I experienced as a child. Even before the war broke out, I sought out our tiny toilet to sit in in silence and to ponder. What I loved at the Zen Center was the sesshin with this incredible availability of energy that manifested directly as awareness, as presence.

Tricycle: Since the only certain event in our lives is death, many traditions offer some kind of “preparation.” In your work, is this something that needs to be integrated into this moment?

Packer: Most of us are afraid of dying. One can try to combat the fear of death by concentrating on death as a practice. Recently I heard of a monastery where the monks were not supposed to talk at all, except for when they met each other they said, “Remember, brother, that you are going to die.” What goes on in these people’s minds? What are they doing in this exercise? Essentially the resistance to being here now is the fear of dying and losing all that we know about ourselves—our whole history. So can one work with this fear directly, listening openly, vulnerably, dying to ideas as they come up about myself and the world? No idea, not being anything, no grasping to be somebody, not anything—when that happens freely there is no fear of dying, because this is what we really are, what we were before we are born, and what we will be when we die. It is our true state. Now. There is nothing fearful about it.

Tricycle: Do you ever think about your own death?

Packer: Sometimes. I wonder how it will be. At the moment of dying I will not be the way I am right now, living. There will be a total letting go of the need to continue. I am sure of that. And that takes care of itself.

Tricycle: How can you be so sure?

Packer: There are times when the concern about death and dying is totally absent. There is just the vastness of purely being here that knows no story about itself. And then there are times when I am thoroughly enjoying being with somebody, or sharing a wonderful meal, or smelling the new spring flowers. And at such a moment I may think, “Oh, someday I may not have this anymore. This marvelous view here of the hills and the snow-covered trees.” Then there could be a twinge of either sadness or nostalgia. But it is becoming increasingly clear that at a moment of dying you simply do not want these things anymore, you are already in a totally different space. You don’t want to keep things, and therefore you are not afraid of losing things.

Tricycle: But how can any of us know what it would be like at that moment?

Packer: You can’t. That is what dying is, not knowing, letting go.

Tricycle: Earlier you referred to letting go of “the Jewish question.”

Packer: Yes. I took a walk during my first sesshin and I saw all of the Halloween litter, and the dead leaves scattered on the pavement. For me the question had been “What is the meaning of this cruel, senseless life?” Of course, part of the senselessness was the Holocaust, doing away with millions and millions of people, not just the Jewish people—a whole slaughter. Then seeing all these leaves on the ground, and the trees weren’t in mourning, the trees weren’t upset, they had new buds. All these leaves were just there. See, how can you explain it? It was all just the way it was. Here was East Avenue, the life, people walking, cars coming by. And then really getting a glimpse of the needlessness of human suffering and the holding on it. Here was a pulsating, aliveness in the presence of leaves on the ground, some of them green, some of them dry, most of them wet. It was so liberating not to have to go on with this story. That this story doesn’t go on forever.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.