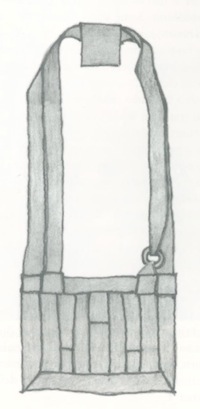

I am sewing my first rakusu—the rectangular bib-like garment that is worn by Zen Buddhists. It is formally conferred during jukai, the ceremony of taking refuge in the Buddha and receiving the precepts. Unlike many people I know, I have never wanted a rakusu. I do have a narrow black doth band (a wagesa) that I received during my first jukai many years ago, but I keep it folded in a comer of my drawer—my sock drawer. Sometimes I feel a pang of remorse that for so long l have allowed it to lie among my socks, socks that slide along the floor and gather dust balls and the smell of sweat and leather. But the truth is that hidden among my socks there are also a few family jewels: an amber bracelet from Poland, a black onyx crucifix that belonged to Great-Aunt Maria, my mother’s moonstone bracelet.

Gradually, as I explore the origin of Buddhist robes and ritual garments, it dawns on me that the mix of lowly socks and precious jewels is in some ways the perfect place in which to have kept my black initiate’s band. For what I discover, as I delve, is a play of opposites that goes back a very long time.

In the traditional telling of Shakyamuni’s life, it is a significant moment when he exchanges his ornate clothes for the tattered robe of a wandering mendicant. Having left his family sleeping in the palace, Prince Siddhartha leapt onto his horse and rode through the night, accompanied only by his servant, Chandaka. Removing his crown, gold, and jewels, he handed them to Chandaka, ordering that they be taken back to the palace. Chandaka begged him to reconsider, but Siddhartha did not yield. Instead, taking Chandaka’s sword, he cut off his own long hair.

At that moment, a deer hunter emerged from the forest. He was dressed very simply, in the saffron robe of a wandering ascetic. Siddhartha asked the man whether he would be willing to exchange his simple robe for the ornate robe of a prince, and the man eagerly agreed. Siddhartha was pleased: now he would have the appearance of an ordinary beggar.

Told in this way, the donning of the saffron robe is an important moment of passage. It takes place at an edge—at a riverbank, just as night has turned to day—and signifies that Siddhartha is at a transition between two lives.

Later, in a practice beginning with the first disciples of the Buddha, this moment of transition—or “going forth”—is repeated in the ritual of ordination. In receiving the robe, the new monk takes on a way of life that is drastically limited, in terms of outward appearance and behavior—yet greatly expanded. For the new robe signifies that the individual has been gathered up into the sangha, the community of those who seek to awaken unlimited mind.

“What the World abandons, the Way uses,” Dogen tells us. … The robe made from a discarded rag is the lotus that grows in mud.

The form of the kasaya, as the robe is called in Sanskrit, is a simple, flat rectangle composed of a number of smaller pieces of fabric. To us, the saffron color appears bright and even flamboyant, but the original meaning of the word kasaya relates to the notion of “impurity.” The color—which contrasted dramatically with the bleached white clothing of the Indian laity—was associated with rotten or poisonous food. The fabric, moreover, was that of pieced rags. The early sutras give explicit directions as to where such rags may be obtained. As summarized by the Japanese Zen master Dogen in his Merit of a Kasaya:

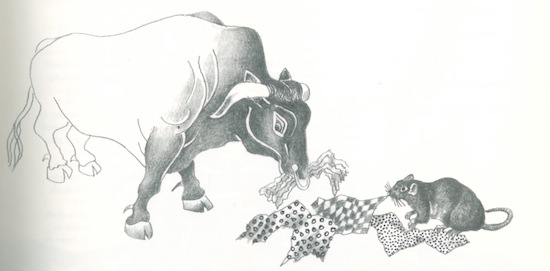

According to the traditional teachings of the Buddhas a kasaya made of discarded cloth, that is, a pamsula (literally, excreta-sweeping cloth) is best. There are either four or ten types of such cloth. The four types of cloth are those that have been burned by fire, munched by oxen, gnawed by mice, or worn by the dead. Indians throw this cloth away in the streets and in the fields just as they do their excreta. The name pamsula comes from this. Monks pick up such cloth and wear it after having washed and sewn the various pieces together.

One can interpret these facts about the kasaya one-dimensionally, as representing a renunciation of worldly values. More profoundly, however, the pamsula represents the process of transformation that is the Buddha Way. When we sit in meditation, we sit in the midst of our own opposites: our strengths and weaknesses, our desires and dislikes. In doing so, we express a willingness to work with everything that arises in the field of our own mind, no matter how great our aversion. “What the World abandons, the Way uses,” Dogen tells us. Understood in this way, the robe made from a discarded rag is the lotus that grows in mud. Indeed, the pieced and patched nature of the kasaya has yet another meaning, as explained in the following ancient story, retold here by Thich Nhat Hanh:

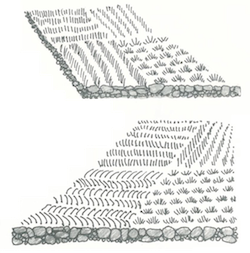

One day while standing on a high hill, the Buddha looked out over the fields of rice paddies. He turned to Ananda and said, “Ananda, how beautiful are the golden patches of rice that stretch to the horizon! Wouldn’t it be nice to sew our robes in the same checkered pattern?”

Ananda said, “Lord, it is a wonderful idea. Sewing bhikkhus’ robes in the same pattern as rice fields would be lovely. You have said that a bhikkhu who practices the Way is like a fertile field in which seeds of virtue and merit have been sown to benefit both the present and future generations. When one makes offerings to such a bhikkhu or studies and practices with him, it is like sowing seeds of virtue and merit. l will tell the rest of the community to sew future robes in the pattern of rice fields. We can call our robes ‘fields of merit.'”

Thus, from the very beginning, the kasaya encompasses that which is discarded, dead, decaying—and that which is beautiful, ordered, nourishing, and growing.

Out of this first fertile layer, new opposites arose. As the Buddha and his circle of disciples began to attract a greater following, the monks found themselves inundated with the gifts of devoted laypeople—and often these gifts included robes. Not wanting to dampen this natural impulse of generosity, Shakyamuni yielded, permitting his monks to accept robes that did not come from the refuse heap. It appears, however, that sometimes the bhikkhus (monks) clung to austerity and refused these gifts. For this reason, according to Walpola Rahula, the Buddha allowed the appointment of a robe-receiving bhikkhu.

Who was this first robe receiver? Did he wear his patchwork cemetery-cloth as he came forward to receive one beautiful robe after another? Was he able to receive the robes with equanimity, or did each one give rise to winds of desire or distaste? What instructions did he leave for his successor?

It is clear that the practice was not an easy one, for Rahula reports that the robe-receiving bhihkhus did not care for them properly. Many of the robes were damaged or destroyed, and so the Buddha had to appoint a robe-depositor bhihkhu, who was charged with properly storing the robes.

The story does not end here, however. It goes on like a comic children’s tale of chain reaction, along the lines of “The House that Jack Built”, or “The Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly”:

Nevertheless there was no appropriate place to store these robes and this resulted in the robes being destroyed by rats, white ants, and the like. Then the Buddha authorized the establishment of a store to keep the robes safely and also the appointment of a Storekeeper bhikkhu to be in charge. Differences of opinion arose among bhikkhus in distributing the robes collected in the store, whereupon the Buddha approved the appointment of a Robe-Distributor bhikkhu to distribute the collected robes among the members of the community. In this manner, more and more rules about robes were introduced.

From the beginning, then, the Buddhist robe has been permeated with the polarities of charnel ground and rice field, ugliness and beauty, pieced and whole, discarded and offered, simple and opulent, gift and burden, unity and disunity, rigidity and flexibility.

Meanwhile, cutting out the black strips for my rakusu, I’m struggling with my own mixed feelings. As a girl, I wanted to be a priest, standing at the altar in green shining robes, lifting the round white wafer above my head and saying, ‘This is my body.” I didn’t want to be a nun, muffled in black, with my bald head constricted in yards of heavy cloth. To me, a nun’s existence was shadowy, repressed.

I tell myself it’s silly to cling to these old images. As I cut, I repeat to myself the words from Hsin Hsin Ming’s Faith Mind: “Even slight distinctions made/ set earth and heaven far apart.” But finally I break down and call my teacher. “I feel like l’m choking on something,” l tell him. “I have a horror of the black cloth.”

“It’s okay,” he says. “Sometimes we just need to duck below our aversions. You can make one out of brown or grey.”

It’s taken me several hours already to cut the black fabric—sixteen pieces in all—but I hang up the phone, dash to the store, and buy a bolt of grey cloth. l still feel that I have succumbed to some small-minded part of myself, but I am grateful for my teacher’s understanding. There is further comfort in realizing that the history of Buddhist clothing is one of experimentation, adaptation, give-and-take.

The willy-nilly patches of the kasaya, for example, gradually turned into neat rectangles, but the number of those rectangles—whether five, seven, nine, or more—varies depending on the particular monastic tradition. And very early on, there was confusion as to how many garments a monk might wear at any one time. According to one account, the Buddha conducted an experiment, sitting in meditation through eight of the coldest nights of the year. He added one robe after another, until the cold no longer penetrated his body. Thus, he determined that three robes were sufficient for even those bhikkhus who were very sensitive to the cold.

In a contemporary Zen monastery in japan, these layers survive as the white juban, a waist-length underkimono; the koromo, a thick, dark blue or black cotton robe with long hanging sleeves; and finally the kesa (Japanese for kasaya). The solid, dark color of most contemporary kesas belies the fact that in Japan the kesa has its own history of opposites. While it has always remained faithful to the patchwork origins of the kasaya, in certain periods of history the patches have been made of beautiful brocades. During the seventeenth century, for example, they were often made of cast-off Noh costumes, ceremonial court robes, or sumptuous kimonos that were the gifts of devout women.

The rakusu is actually an abbreviated version of the kesa. According to some accounts, it evolved in response to a period of persecution in China during which monks and nuns had to return to lay life. Unable to wear their traditional robes, they fashioned the rakusu and wore it under their clothing. Like the kesa, it is formed of a patchwork of strips. In modern-day Japan, it is worn by monks as a less formal alternative to the kesa. In both Japan and the West, it is worn by laypeople during meditation. Although the rakusu is traditionally a dark, solid color, a more ornate, brocaded one is often given to a new Zen teacher during the ceremony of transmission.

Now that the gray cloth has released me from my nun fears, l’m dealing with the next layer of resistance. To put it bluntly: I don’t want anything around my neck. I balk at feeling encumbered. Yet I know that the very origin of the word religion carries the meaning of tying back and that the words yoga and yoke are etymologically linked. I accept the need for forms, remembering too well the pain of being pathless. Indeed, though it’s been more than twenty years since a young monk from Thailand first showed me how to sit cross legged on a cushion, I still sometimes—in the midst of bowing or chanting—have to blink back tears of relief.

What holds me back, then? On one level, my resistance is nothing more than a form of clinging to my own idiosyncrasies. I have always disliked being easily identified, and I have a horror of uniforms. At another level, I resist the clubbiness, the aura of hierarchy and exclusivity, associated with the rakusu. I have experienced, in more than one Zen community, that the rakusu is a highly coveted badge, giving rise to distinctions between in-group and out-group, to waves of longing and envy.

There is a point at which these feelings of unease sink much deeper; however, approaching the level of dynamic question. Why, if in practicing the Buddha Way we seek to discover the oneness of all beings, should we differentiate ourselves in outward appearance? Why, if our own true nature is formless, unborn, and undying, should we express this through limited form? If our practice is that of seeing into—and becoming one with—the unconditioned, then why do we act conditionally, responding to a particular circumstance in a particular way, rising to put on our priest’s robe at the sound of a bell?

It is here, in asking these questions, that the act of putting on the Buddha’s robe takes on another dimension. Now it is something far more than a significant moment of transition, a passage between one way of life and another. For now, at the deepest level, it is the practice of asking the question “How does the Buddha manifest in this world?”

Now we can understand why the Buddha’s robe is, as a symbolic object, so highly charged—appearing in numerous legends, teaching stories, and koans. For it is a particular thing that we put on in a particular way to announce our commitment to that which is beyond all particular determination: no color, sound, smell, taste, touch. It thus embodies one of the most fundamental questions in Buddhism: the mystery of the relationship between relative and absolute.

It also embodies another central question: that of our relationship to the lineage. In putting on the Buddha’s robe, we announce that we are followers of the Buddha—and of all the buddhas before and after him—but what does this mean?

It is this question that, more than any other, is at the root of Dogen’s words on the kasaya. At first this may be hard to see, for much of what he says is meticulously—even fanatically—detailed. For example:

The unfolded kasaya should be put in a clean wooden tub. Then, adding fragrant boiling hot water, let it soak for approximately two hours. Then, hold it with both hands, being careful not to crumple it up or trample on it. Continue washing the kasaya until all the dirt and grease have been removed. When this has been done, rinse the kasaya in cold water containing incense of aloes or beadwood, and so on. After having dried it thoroughly on a clean rod, fold it and put it in an elevated place. Then burning incense and scattering flower petals, walk clockwise around it several times, prostrating yourself before it three, six, or nine times.

In fact, Dogen moves seamlessly between the literal, devotional, and magical aspects of the kasaya. For him these aspects are inseparable, all of them converging in the awesome phenomenon of transmission. After giving detailed advice as to how to sew, wash, dry, fold, and put on the kasaya, he can in the next breath declare, “When you put on the kasaya, it is the same as when a prince ascends the throne.” Understood in this light, to put on—to really put on—the kasaya is to throw one’s life into asking the question “How does Buddha become Buddha?”

My rakusu is not made of bits of cloth from the refuse heap, but it arises from a mixture of many things: gratitude to my teacher and sangha—but also pride, distrust, and painful memories. As I sew through this mishmash, arranging the strips in their crisscross pattern, stitching the band that will go around my neck, I feel my rakusu opening wider and wider. It is, indeed, becoming a field. This vastness is expressed in the verse that I will say—like a monk rising at the sound of a bell—each time I put it on:

How great and wondrous is the robe of enlightenment,

Formless, yet embracing every treasure!

l wish to unfold the Buddha’s teaching,

That l may help all living things.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.