The Heart of Being: Moral and Ethical Teachings of Zen Buddhism

John Daido Loori

Charles E. Tuttle Co.: Boston, 1996.

267 pp., $16.95 (paper)

Near the end of this book dense with principles and interpretations, John Daido Loori writes that it is vital to “take the teachings out of the theoretical and abstract mode and thrust them into the present moment.”

Loori then recounts the story of a dharma teacher in America who knew that he was infected with the virus that causes AIDS and yet had sexual relationships with students. He “essentially made the statement that his realization, his enlightenment, enabled him to transcend cause and effect,” Loori writes. The teacher has since died, his community of practitioners has virtually broken down, and at least one person has been infected with AIDS virus.

“What would you do?” Loori asks. “How would you have handled that situation as the teacher? How would you turn it around?”

Until that point, Loori essentially provides an exhaustive presentation of and commentary on the Buddhist precepts, which, he writes, are “the definition of the life of the Buddha.” But from the outset, with the tolling of a bell in the introduction, Loori strides into the complex moral and ethical fray of modern society.

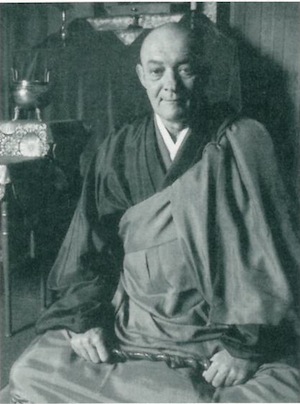

Loori, abbot and spiritual leader of Zen Mountain Monastery in Mount Tremper, New York, and the author of Two Arrows Meeting in Mid-Air (Tuttle) among other books, presents the precepts as they are interpreted, studied, and lived in his community of lay followers and monastics. His book’s rigor and formality reflect that of the Mountains and Rivers Order, which he founded and leads.

We learn early on that his students receive the precepts, a kind of Buddhist rite of passage, only after having completed at least one year of training as a “formal” student and one year of formal precept study, which includes reading and academic study, intensive meditation, performance of liturgical functions, and attendance at monthly “renewal of vows” ceremonies. Finally, a week of residential training culminates with the traditional jukai ceremony, during which Loori “gives” the precepts to the student, who vows to maintain them.

Loori uses the forms of the ceremony and the various vows as the structure for the first part of the book. There is a chapter on the “sacred space” of the ceremony, a chapter on atonement, chapters on the three “pure” precepts and one on the ten “grave” precepts, a chapter on the four Bodhisattva Vows that are recited daily by Zen practitioners. He describes these forms in detail and comments on them at length.

The reader, however, misses something fundamental. We are left with page after page of talk about the precepts and about morals and ethics and principles, of interpretation and commentary. Yet what is there really to say about the precepts except, “Be them. You are them”? Which, of course, Loori says in a number of ways.

A far more eloquent teaching would have been to give us himself as the precepts, to offer us his own vibrant experiences of them. How, on any given day, in any given moment, does he, John Daido Loori, experience the precepts in his life, as his life?

This is not to say that the book is bereft of the concrete. To illustrate a koan on giving, for instance, there is a fine account of a conflict between Loori’s community and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. There is the story of the AIDS-infected teacher. A chapter on the precepts and the environment hums with simple, living examples culled from nature.

Much of this comes in the latter portion of the book, in the second and third parts, which are devoted to several koans presented in a moral and ethical light and to a series of question-and-answer exchanges between Loori and his students. And unfortunately, some examples are repeated in different sections, which renders them curiously lifeless, like standard props brought out on cue for support.

This is not simply a question of satisfying a preference for experience over concept. It strikes to the very heart of the subject, which, as the title says, is the heart of being. Loori himself writes that “personal experience” is the “bottom line” in Zen practice, not “understanding or belief.” With this experience, with the realization of one’s true nature and the fundamental nature of all things, comes the realization of the precepts. “Right” ethics, “right” morals, “right” action are the result of integrating this realization into the whole of one’s being; even lifetimes of study will never do it.

Loori tells us this (“All the precepts are nothing other than the life of no-self”) but he does not show us. Without this manifestation, the precepts as presented conceptually here risk being interpreted as a fixed, dualistic code of conduct, giving rise to conditioned “right” response and inhibition of what is considered “wrong” behavior. There is even separation inherent in the notion of “practicing” the precepts, suggesting that they are something outside of you to be followed.

As Loori notes repeatedly, the precepts are constantly new, alive, and changing in each instant and each circumstance. Life—or, as he writes, “the whole catastrophe”—is every moment. His is thus a formidable undertaking, and his generous effort brought me again and again to the essential question of what, after all, is essential. Ultimately, there is no one answer to that question. Loori’s book, however, encourages us to keep asking.

Amy Hollowell is an editor at the International Herald Tribune in Paris.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.