Perhaps because of both its profundity and its brevity, the Heart Sutra is the most familiar of all the original teachings of the Buddha. (The Sino-Japanese version comprises a mere 262 characters.) Recited daily by Buddhists in China, Korea, Vietnam, Japan, Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan, Nepal, the Heart Sutra is now also recited by many Buddhists in North America. The Sino-Japanese and monosyllabic Korean versions lend themselves well to chanting, and there are now several English translations. The basic text of the Zen tradition, it must also be the only sutra to be found (in Japan) printed on a man’s tie.

According to Buddhist lore, the Heart Sutra was first preached on Vulture Peak, which lies near the ancient Indian city of Rajagraha, and is said to have been the Buddha’s favorite site.

In this sutra, the Buddha inspires one of his closest disciples, Sariputra, to request Avalokitesvara, the Bodhisattva of compassion, to instruct him in the practice of prajnaparamita, the perfection of wisdom. Avalokitesvara’s response contains one of the most celebrated of all Buddhist paradoxes—”form is emptiness; emptiness is form.” And the sutra ends with one of the most popular Buddhist mantras—gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi svaha: gone, gone, gone beyond, gone completely beyond…(When chanted, gate has two short vowels with the accent on the first syllable.)

The tradition of composing commentary on the Heart Sutra goes back to at least the eighth century, and includes many of the great Buddhist philosophers and meditation masters. What follows here are versions of the sutra and excerpts from some contemporary commentaries addressed to Westerners.

English translations of Buddhist language are not standardized. Variations of, for example, “Avalokitesvara” or “sunyata” or “sutra” reflect differences between Pali and Sanskrit, as well as the national origins of the translators.—Ed.

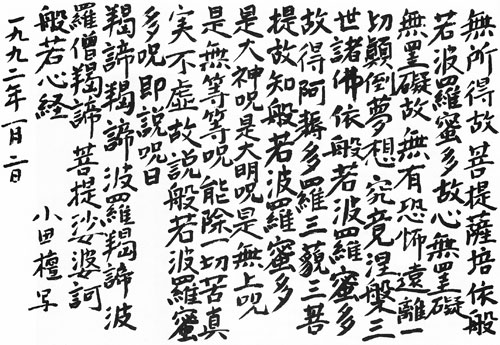

THE GREAT PRAJNA PARAMITA HEART SUTRA

From the sutra book used by The Zen Community of New York.

Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva doing deep Prajna Paramita

Perceived the emptiness of all five conditions, and was freed of pain.

O Sariputra, form is no other than emptiness, emptiness no other than form;

Form is precisely emptiness, emptiness precisely form;

Sensation, perception, reaction and consciousness are also like this.

O Sariputra, all things are expressions of emptiness, not born, not destroyed,

Not stained, not pure; neither waxing nor waning.

Thus emptiness is not form; not sensation nor perception, reaction nor consciousness;

No eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, mind;

No color, sound, smell, taste, touch, thing

No realm of sight, no realm of consciousness

No ignorance, no end to ignorance

No old age and death, no cessation of old age and death

No suffering, no cause or end to suffering, no path

No wisdom and no gain. No gain—thus

Bodhisattvas live this Prajna Paramita

With no hindrance of mind—no hindrance therefore no fear

Far beyond all such delusion, Nirvana is already here.

All past, present, and future Buddhas live this Prajna Paramita

And attain supreme, perfect enlightenment.

Therefore know that Prajna Paramita is

The holy mantra, the luminous mantra

The supreme mantra, the incomparable mantra

By which all suffering is cleared. This is no other than truth.

Therefore set forth the Prajna Paramita mantra,

Set forth this mantra and proclaim:

Gate Gate Paragate Parasamgate Bodhi Svaha!

Commentary by Thich Nhat Hanh

Perfect understanding is prajnaparamita. The word “wisdom” is usually used to translate prajna, but I think that wisdom is somehow not able to convey the meaning. Understanding is like water flowing in a stream. Wisdom and knowledge are solid and can block our understanding. In Buddhism, knowledge is regarded as an obstacle for understanding. If we take something to be the truth, we may cling to it so much that even if the truth comes and knocks at our door, we won’t want to let it in. We have to be able to transcend our previous knowledge the way we climb up a ladder. If we are on the fifth rung and think that we are very high, there is no hope for us to step up to the sixth. We must learn to transcend our own views. Understanding, like water, can flow, can penetrate. Views, knowledge, and even wisdom are solid, and can block the way of understanding.

Avalokita found the five skandhas empty. But, empty of what? The key word is empty. To be empty is to be empty of something.

If I am holding a cup of water and I ask you, “Is this cup empty?” you will say, “No, it is full of water.” But if I pour out the water and ask you again, you may say, “Yes, it is empty.” But, empty of what? Empty means empty of something. The cup cannot be empty of nothing. “Empty” doesn’t mean anything unless you know empty of what. My cup is empty of water, but it is not empty of air. To be empty is to be empty of something. This is quite a discovery. When Avalokita says that the five skandhas are equally empty, to help him be precise we must ask, “Mr. Avalokita, empty of what?”

The five skandhas, which may be translated into English as five heaps, or five aggregates, are the five elements that comprise a human being. These five elements flow like a river in every one of us. In fact, these are really five rivers flowing together in us: the river of form, which means our body, the river of feelings, the river of perceptions, the river of mental formations, and the river of consciousness. They are always flowing in us. So according to Avalokita, when he looked deeply into the nature of these five rivers, he suddenly saw that all five are empty. And if we ask, “Empty of what?” he has to answer. And this is what he said: “They are empty of a separate self.” That means none of these five rivers can exist by itself alone. Each of the five rivers has to be made by the other four. They have to co-exist; they have to inter-be with all the others.

Avalokita looked deeply into the five skandhas of form, feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness, and he discovered that none of them can be by itself alone. Each can only inter-be with all the others. So he tells us that form is empty. Form is empty of a separate self, but it is full of everything in the cosmos. The same is true with feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness.

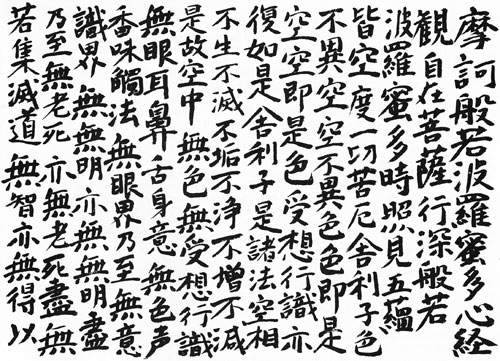

THE SUTRA OF THE HEART OF TRANSCENDENT KNOWLEDGE

The Nalanda Translation Committee, under the direction of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, translated this version of the Heart Sutra from Tibetan. Reprinted with the permission of the Nalanda Translation Committee, Halifax, N.S. Copywrite 1978 Chogyam Trungpa.

Thus have I heard. Once the Blessed One was dwelling in Rajagriha at Vulture Peak mountain, together with a great gathering of the sangha of monks and a great gathering of the sangha of bodhisattvas. At that time the Blessed One entered the samadhi that expresses the dharma called “profound illumination,” and at the same time noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva, while practicing the profound prajnaparamita, saw in this way: he saw the five skandhas to be empty of nature.

Then, through the power of the Buddha, venerable Shariputra said to noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva, “How should a son or daughter of noble family train, who wishes to practice the profound prajnaparamita?”

Addressed in this way, noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva, said to venerable Shariputra, “O Shariputra, a son or daughter of noble family who wishes to practice the profound prajnaparamita should see in this way: seeing the five skandhas to be empty of nature. Form is emptiness; emptiness also is form. Emptiness is no other than form; form is no other than emptiness. In the same way, feeling, perception, formation, and consciousness are emptiness. Thus, Shariputra, all dharmas are emptiness. There are no characteristics. There is no birth and no cessation. There is no impurity and no purity. There is no decrease and no increase. Therefore, Shariputra, in emptiness, there is no form, no feeling, no perception, no formation, no consciousness; no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind; no appearance, no sound, no smell, no taste, no touch, no dharmas; no eye dhatu up to no mind dhatu, no dhatu of dharmas, no mind consciousness dhatu; no ignorance, no end of ignorance up to no old age and death, no end of old age and death; no suffering, no origin of suffering, no cessation of suffering, no path, no wisdom, no attainment, and no nonattainment. Therefore, Shariputra, since the bodhisattvas have no attainment, they abide by means of prajnaparamita. Since there is no obscuration of mind, there is no fear. They transcend falsity and attain complete nirvana. All the buddhas of the three times, by means of prajnaparamita, fully awaken to unsurpassable, true, complete enlightenment. Therefore, the great mantra of prajnaparamita, the mantra of great insight, the unsurpassed mantra, the unequaled mantra, the mantra that calms all suffering, should be known as truth, since there is no deception. The prajnaparamita mantra is said in this way:

OM GATE GATE PARA GATE PARASAMGATE BODHI SVAHA

Thus, Shariputra, the bodhisattva mahasattva should train in the profound prajnaparamita.” Then the Blessed One arose from that samadhi and praised noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva, saying, “Good, good, O son of noble family; thus it is, O son of noble family, thus it is. One should practice the profound prajnaparamita just as you have taught and all the tathagatas will rejoice.” When the Blessed One had said this, venerable Shariputra and noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva, that whole assembly and the world with its gods, humans, asuras, and gandharvas rejoiced and praised the words of the Blessed One.

Commentary by Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

Cutting through our conceptualized versions of the world with the sword of prajna, we discover shunyata—nothingness, emptiness, voidness, the absence of duality and conceptualization. The best known of the Buddha’s teachings on this subject are presented in the Prajnaparamita-hridaya, also called the Heart Sutra; but interestingly in this sutra the Buddha hardly speaks a word at all. At the end of the discourse he merely says, “Well said, well said,” and smiles. He created a situation in which the teaching of shunyata was set forth by others, rather than himself being the actual spokesman. He did not impose his communication but created the situation in which teaching could occur, in which his disciples were inspired to discover and experience shunyata. There are twelve styles of presenting the dharma and this is one of them.

This sutra tells of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva who represents compassion and skillful means, and Shariputra, the great arhat who represents prajna, knowledge. There are certain differences between the Tibetan and Japanese translations and the Sanskrit original, but all versions make the point that Avalokiteshvara was compelled to awaken to shunyata by the overwhelming force of prajna. Then Avalokiteshvara spoke with Shariputra, who represents the scientific-minded person or precise knowledge. The teachings of the Buddha were put under Shariputra’s microscope, which is to say that these teachings were not accepted on blind faith but were examined, practiced, tried and proved.

Avalokiteshvara said: “Oh Shariputra, form is emptiness, emptiness is form; form is no other than emptiness, emptiness is no other than form.” We need not go into the details of their discourse, but we can examine this statement about form and emptiness, which is the main point of the sutra. And so we should be very clear and precise about the meaning of the term “form.”

Form is that which is before we project our concepts onto it. It is the original state of “what is here,” the colorful, vivid, impressive, dramatic, aesthetic qualities that exist in every situation. Form could be a maple leaf falling from a tree and landing on a mountain river; it could be full moonlight, a gutter in the street or a garbage pile. These things are “what is,” and they are all in one sense the same: they are all forms, they are all objects, they are just what is. Evaluations regarding them are only created later in our minds. If we really look at these things as they are, they are just forms.

So form is empty. But empty of what? Form is empty of our preconceptions, empty of our judgments. If we do not evaluate and categorize the maple leaf falling and landing on the stream as opposed to the garbage heap in New York, then they are there, what is. They are empty of preconception. They are precisely what they are, of course! Garbage is garbage, a maple leaf is a maple leaf, “what is” is “what is.” Form is empty if we see it in the absence of our own personal interpretations of it.

But emptiness is also form. That is a very outrageous remark. We thought we had managed to sort everything out, we thought we had managed to see that everything is the “same” if we take out our preconceptions. That made a beautiful picture: everything bad and everything good that we see are both good. Fine. Very smooth. But the next point is that emptiness is also form, so we have to re-examine. The emptiness of the maple leaf is also form; it is not really empty. The emptiness of the garbage heap is also form. To try to see these things as empty is also to clothe them in concept. Form comes back. It was too easy, taking away all concept, to conclude that everything simply is what is. That could be an escape, another way of comforting ourselves. We have to actually feel things as they are, the qualities of the garbage heapness and the qualities of the maple leafness, the isness of things. We have to feel them properly, not just trying to put a veil of emptiness over them. That does not help at all. We have to see the “isness” of what is there, the raw and rugged qualities of things precisely as they are. This is a very accurate way of seeing the world. So first we wipe away all our heavy preconceptions, and then we even wipe away the subtleties of such words as “empty,” leaving us nowhere, completely with what is.

Finally we come to the conclusion that form is just form and emptiness is just emptiness, which has been described in the sutra as seeing that form is no other than emptiness, emptiness is no other than form; they are indivisible. We see that looking for beauty or philosophical meaning to life is merely a way of justifying ourselves, saying that things are not so bad as we think. Things are as bad as we think! Form is form, emptiness is emptiness, things are just what they are and we do not have to try to see them in the light of some sort of profundity. Finally we come down to earth, we see things as they are. This does not mean having an inspired mystical vision with archangels, cherubs and sweet music playing. But things are seen as they are, in their own qualities. So shunyata in this case is the complete absence of concepts or filters of any kind, the absence even of the “form is empty” and the “emptiness is form.”

Excerpted from Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism and reprinted with permission from Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Commentary by Shunryu Suzuki Roshi

In the Prajna Paramita Sutra the most important point, of course, is the idea of emptiness. Before we understand the idea of emptiness, everything seems to exist substantially. But after we realize the emptiness of things, everything becomes real—not substantial. When we realize that everything we see is a part of emptiness, we can have no attachment to any existence; we realize that everything is just a tentative form and color. Thus we realize the true meaning of each tentative existence. When we first hear that everything is a tentative existence, most of us are disappointed; but this disappointment comes from a wrong view of man and nature. It is because our way of observing things is deeply rooted in our self-centered ideas that we are disappointed when we find everything has only a tentative existence. But when we actually realize this truth, we will have no suffering.

This sutra says, “Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara observes that everything is emptiness, thus he forsakes all suffering.” It was not after he realized this truth that he overcame suffering—to realize this fact is itself to be relieved from suffering. So realization of the truth is salvation itself. We say, “to realize,” but the realization of the truth is always near at hand. It is not after we practice zazen that we realize the truth; even before we practice zazen, realization is there. It is not after we understand the truth that we attain enlightenment. To realize the truth is to live—to exist here and now. So it is not a matter of understanding or of practice. It is an ultimate fact. In this sutra Buddha is referring to the ultimate fact that we always face moment after moment. This point is very important. This is Bodhidharma’s zazen. Even before we practice it, enlightenment is there. But usually we understand the practice of zazen and enlightenment as two different things: here is practice, like a pair of glasses, and when we use the practice, like putting the glasses on, we see enlightenment. This is the wrong understanding. The glasses themselves are enlightenment, and to put them on is also enlightenment. So whatever you do, or even though you do not do anything, enlightenment is there, always. This is Bodhidharma’s understanding of enlightenment.

Excerpted from Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind and reprinted with permission from Weatherhill Press.

THREE COMMENTARIES ON THE GREAT MANTRA

Set forth this mantra and proclaim:

Gate Gate Paragate Parasamgate Bodhi Svaha!

Mu Soeng Sunim

Gate gate means gone, gone; paragate means gone over; parasamgate means gone beyond (to the other shore of suffering or the bondage of samsara); bodhi means the Awakened Mind; svaha is the Sanskrit word for homage or proclamation. So, the mantra means “Homage to the Awakened Mind which has gone over to the other shore (of suffering).”

Whatever perspective one may take on the inclusion of the mantra at the end of the sutra, it does not put a blemish on what the sutra has tried to convey earlier: the richness of intuitive wisdom coming out of the pure experience of complete stillness, of complete cessation, away from all concepts and categories.

Zen masters, in echoing the theme of emptiness, like to agree with existentialist thinkers that “life” has no meaning or reason. The Heart Sutra uses the methodology of negation as a way of pointing to this lack of any inherent meaning or reason in the phenomenal world, including the world of the mind. It takes each of the existents, holds it up under an unflinching gaze and declares it to have no sustaining self-nature. This is the wisdom teaching of sunyata of the Mahayana tradition. But, at the same time, compassion is the other and equally important teaching of Mahayana. How do we then bridge the gap between sunyata as ultimate reality and the conventionality of human existance? The existentialist thinkers agonized over this problem and were led to despair and anarchy. In Mahayana, compassion, which is a natural, unenforced by-product of a deep state of meditation, supports the wisdom of emptiness, yet allows the individual to have empathy with the conventional appearance of the world without getting lost in it. It may be that compassion works best as a post-enlightenment existential crisis, but nonetheless without compassion as a guiding paradigm, the unrelenting precision of sunyata can make life bearable.

Excerpted from Heart Sutra: Ancient Wisdom in the Light of Quantum Reality and reprinted with permission from Primary Point Press.

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

The Heart Sutra ends with “the great spell” or mantra. It says in the Tibetan version: “Therefore the mantra of transcendent knowledge, the mantra of deep insight, the unsurpassed mantra, the unequalled mantra, the mantra which calms all suffering, should be known as truth, for there is no deception.” The potency of this mantra comes not from some imagined mystical or magical power of the words but from their meaning. It is interesting that after discussing shunyata—form is empty, emptiness is form, form is no other than emptiness, emptiness is identical with form and so on—the sutra goes on to discuss mantra. At the beginning it speaks in terms of the meditative state, and finally it speaks of mantra or words. This is because in the beginning we must develop a confidence in our understanding, clearing out all preconceptions; nihilism, eternalism, all beliefs have to be cut through, transcended. And when a person is completely exposed, fully unclothed, fully unmasked, completely naked, completely opened—at that very moment he sees the power of the word. When the basic, absolute, ultimate hypocrisy has been unmasked, then one really begins to see the jewel shining in its brightness: the energetic, living quality of openness, the living quality of surrender, the living quality of renunciation.

Excerpted from Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism and reprinted with permission from Shambhala Publications.

Taizan Maezumi Roshi

If you read the Hannya Shingyo (Heart Sutra) carefully, there is quite a thorough explanation of the direction to follow. Furthermore, every morning we chant “Gate Gate Paragate Parasamgate Bodhisvaha.” That’s another direction. Not only just make yourself go in a nice direction—whatever, wherever you want to go. But parasangha—“with the Sangha,” with everybody—go that way. Go to the other shore. Paramita. Realize, reach the other shore. Realize that paradise or heavenly dwelling, or happy, peaceful dwelling; whatever it is. See that dwelling place in which we live together. That’s the direction to go. And what’s the paradise? Where is it? Needless to say, right beneath your feet.

Excerpted from a dharma talk to students at Zen Mountain Center in California.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.