Carol Wilson grew up in the town of Huntington, on New York’s Long Island, in what she calls a typical middle-class home. Her father was an airline pilot, which explains her itch to travel, she thinks, and her mother took care of the three children—Carol, her sister, and brother. She discovered Buddhism in her teens, “the only thing,” she says, ”that has ever fired me up”—so much so that she kept interrupting her education to follow the dharma.

Wilson first went to India in l971, when she was 19, after one semester at NYU and a stint working in a hospital kitchen to raise money for travel. In India she attended her first retreat, with the Burmese meditation teacher S. N. Goenka, known for his exacting teaching style. Like many Western students of her generation, Wilson later studied with a number of teachers from various traditions. She eventually arrived at Insight Meditation Society (IMS), in Barre, Massachussetts, where she is now a guiding teacher. She teaches the way she talks—she’s down-to-earth, funny, bringing the dharma into everyday life and bringing life into the dharma.

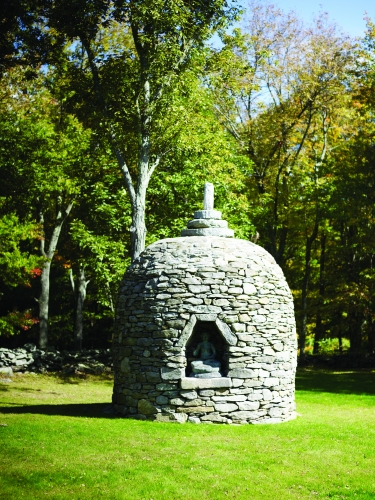

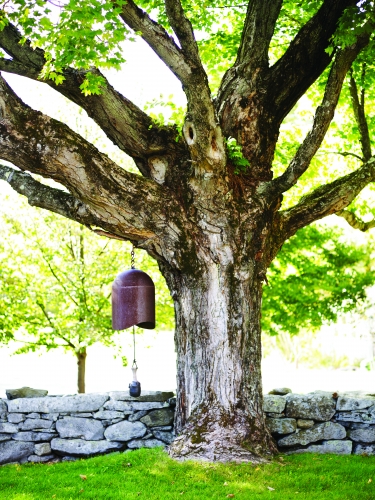

Tricycle contributing editor Amy Gross interviewed Carol Wilson in her cottage at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies, a short walk from IMS.

What got you, a 19-year-old product of Long Island suburbia, to leave college to go sit in India? When I was 16, 17, I had some experiences with psychedelics that had the effect, as it did on many people, of shifting my view of the world. It just opened things up. I started reading Zen books, which I didn’t understand at all—I was 16, what did I know?—but when I look back now, something got sparked. I didn’t get that the Goenka retreat was really Buddhism, but it totally changed my life. I came out thinking not, “Oh, I’ve got to stay and do this,” but more— and this has been a conflict all my life—“I should go back and do something useful to help people.” My idea was that I should teach, and I finally got a B.A. in Special Ed. But the dharma, meditation, completely took everything in me. I didn’t realize you could make it your whole life. Then IMS started, and I heard they had a three-month retreat. That was ’77, their second one. So I quit [teaching] and I went to the three-month retreat. It was like, “Oh God, I’m home.” At the end of the retreat I would have left, but they needed a cook. Someone asked me to do it—I never would have thought of it. I remember telling Jack [Kornfield, one of IMS’s founding teachers], “I don’t know how to cook for a lot of people.” And he goes, “Well, can you learn?” I thought, and I said, “Yeah, I can learn.” And that was it.

Who else had an impact on your practice? There were Joseph Goldstein and Christopher Titmuss. In Thailand [where Wilson temporarily ordained as a nun], it was the quiet life in the forest that was the teacher. You wake up, you sew your little underwear, you sweep, you eat your one meal a day—it takes time for the mind and the heart to settle into that simplicity. And it was wonderful.

[The Burmese master] Sayadaw U Pandita was also very powerful for me. If you really practice the technique [noting what arises in awareness, moment to moment] with 100 percent commitment, I think it can take you to freedom. You actually experience impermanence and not-self and suffering—dukkha, the unreliable nature of things.

This is an interesting time in the story of Buddhism in the West. Many of us are mixing practices from Vipassana, Zen, and Tibetan, building our own individual fusion dharmas. You began with Zen, then moved through orthodox Indian Vipassana to Burmese. Were there other teachers who shifted your practice? I guess Poonjaji [H. W. L. Poonja] was the next big influence. That’s Advaita Vedanta. He was a student of Ramana Maharshi [the Hindu sage], and I spent several months in Lucknow with him. Partly I just loved being out of the Vipassana scene, even though half the people there were from the Vipassana world.

Escapees from Vipassana? Well, see—that’s not escaping. Here’s an example of the split so many people get into, thinking that if you’re doing Advaita, there must be something wrong with Vipassana. There’s so much sectarianism that goes on. One of the things that helps to break out of sectarianism is to see how, as you said, each of us is doing our own fusion. You can go from a really focused, samadhi-based kind of practice—like Goenka’s and U Pandita’s—to something more open, like what Munindra [the Indian teacher] practiced. When Joseph first started teaching, he taught what Munindra taught: “Just sit and know you’re sitting, and the whole dharma unfolds by itself.” I’d been practicing with U Pandita for several years, noting experience—note, note, note, 60 notings per minute—and I’d gone from being fascinated to feeling tight, kind of dry. Something was missing for me. Friends of mine had been to Poonjaji, so I went to see him in February ’91 and then again for several months that fall. It was a great, happy time. Poonjaji would talk about just “knowing the source.” He was always looking back at the source—his word for awareness. He said some people call it love, other people call it compassion or emptiness, and some people call it joy.

After Poonjaji, I didn’t really connect with a teacher for a while. I started to feel the lack of that kind of input—I felt like I was making up my own, you know, fusion. When I met [the Burmese teacher] Sayadaw U Tejaniya, I thought, he’s the missing link for me between Theravada and Advaita, yet he’s a totally Theravada teacher. Plus, I like him. He’s funny, he’s down to earth. He spent most of his life as a layman. He’s been through stuff, he’s been through life. I could talk to him.

What’s the essence of U Tejaniya’s teaching for you? If you had to say what kind of tagline he’s known by, it’s practicing with right attitude more than any particular technique. Right attitude is just checking what qualities, what mental factors, are present in the mind that‘s meditating. When we’re not aware of what’s present in our consciousness, we’re looking through its lens and it colors everything we’re doing. If we’re filled with greed and don’t see it, greed is in the background and can be driving whatever we’re doing.

U Tejaniya is all about noticing what’s in the mind in any moment of the day. Noticing when there’s greed or various forms of ill will or hatred or delusion. It doesn’t just have to be difficult stuff—you could check and see there’s interest, there’s samadhi [stability of mind] or metta [lovingkindness] or wisdom. It becomes second nature to check what’s going on in your mind— not just a few times an hour but always. Opening your attention. For me, it’s a feeling of “What’s in the mind?”

The essence of his teaching is relax, because mostly we’re trying to do something when we’re meditating, not noticing that “trying” is more often coming from wanting and self than anything else. And when you see the wanting, you just have to notice it and see wanting, wanting—you know? So right attitude in meditating and practicing is when the mind is not colored by greed or ill will or hatred or confusion. Then we can investigate, and wisdom will develop.

And you’re investigating all the time—not just when you’re sitting. U Tejaniya’s main thing is watching your mind all the time. He developed this approach as a layman, so it’s not about just being on intensive silent retreat. He has one line I really love: he calls watching the mind “a secret mission.” When he was working—he sold clothes in a stall—he’d go with his friends to a bar or a boxing match, but all he was interested in, he said, was watching his mind. So you can be with people; they don’t know what you’re doing—it’s a secret mission. You’re just watching what’s going on in your mind all the time. He says we tend to be either completely internal—looking at our stuff—or we get involved in the external and completely lose it. He’s saying: “Remember yourself, all day, every day, and mindfulness will develop a momentum.” Keep your attention 50/50 or 60/40—60 percent with yourself, 40 percent on the external. And relax; it doesn’t take a lot of force.

As soon as I remember myself, I’m here. I just relax and feel my body. Right away I can notice: my mind feels a little tired, a little heavy, but otherwise pretty calm. And I found that translated into my daily life more than anything else.

I still love intensive retreat and silence. But Sayadaw U Te- janiya doesn’t feed into the idea that retreat is superior to everyday life. He’s lifted the sense that practice has to be so forced, or that you need results like concentration states or insights. Practice becomes fun. You just want to see what’s going on in the mind. It’s fascinating.

You just drop in the question: What’s the attitude in the mind? Yes. There’s no “I” there. That’s a lot of the genius of it: he so emphasizes just relaxing, not striving. Effort always has a little sense of me in it. So yes, once you get used to doing it, it’s not me doing anything and there’s no place I’m trying to get to. It just opens up. You see how relaxing takes away that self-defense, that kind of judging? What’s to judge? It’s just dosa [Pali, “aversion”] in the mind: it comes like this, it has this effect; this feeds it, this doesn’t feed it. The other way—when I’m noting each thought very carefully, I keep looking at the person I’m angry with in my mind, and the anger actually gets stronger. But if I go, “dosa in the mind,” sometimes it goes away, and other times I can’t be with it. One sitting with U Tejaniya, I felt this energy in my body, very uncomfortable, like restless leg but all over. It was really hard to just watch the aversion and the impatience. I was describing it to him later, and I said I couldn’t bear to be there with it. He said, “Who said you had to be with it?” [Laughs.] He’s really great at hearing all the little assumptions we’re bringing in. That’s another place he’ll always go: what are the ideas working in the back of your mind that we mostly don’t look at? Part of watching the attitude in your mind is asking: What are the assumptions we’re bringing in? Like: I should be with it.

A lot of the work of teachers, I think, is just to help us reconnect to that interest and that fire, that willingness to look at the truth, at how it is. Reality is how it is. That’s another thing U Tejaniya says: “Reality is already the way it is. You don’t have to create anything. You just have to have a clear mind that isn’t colored.”

In another talk, you said, “No matter how terrible any feeling or thought is, connecting with it will be soothing.” You said that if you shut off awareness of one thing, you shut off everything. I had a very hectic drive up here, and I’d say to myself, “This is just the way it is right now.” And all the tension dissolved. Isn’t it amazing? What keeps us suffering is holding off unpleasant, scary things, or the habit of fearing something we don’t even know we’re holding off. Then we open to it and know, okay, this feels like shit, but there’s no separation of it and me.

For instance, with anxiety: opening to it, accepting how it is, and then somehow it isn’t a problem. Really for me now, the only problem with anxiety or anything is when there’s a sense of referral back to me—I’m anxious. Anxiety is just anxiety. It’s just what it is.

Accepting suffering as impersonal avoids the self-blame that usually arises when things get uncomfortable. On one retreat, a man complained that his mind was clear in the morning, but in the afternoon he’d get sleepy and at night his concentration was erratic. You started laughing. You said something like, “Are you hearing yourself? You’re saying that your practice isn’t exactly the way you want it to be.” The whole room got it: things change, and that’s just the way things are. We’ve all heard that seven thousand billion times. But our mind is just so familiar with grasping. It feels so like home. This takes us back to U Tejaniya’s “What idea is working in the back of your mind?” We could all spout about how we know it’s not true, but in the back of our mind, somehow, is the idea freedom is going to be “I’m always happy and peaceful.” And it’s unnecessary, it’s extra. I’ve been noticing lately that, say, if a car pulls out in front of me, a moment of aversion shoots up that’s completely unnecessary. I have to slow down—that’s necessary, but does it have to be a problem? Now I sense right away how yucky it feels. And then pretty much it’s over, unless I’m having a bad, down-on-myself day and self-judgment is strong in the mind. Then you can see how one moment leads to the next. That whole sense of self and our stories and all of that—it’s really extra.

I like the idea of using the “yucky feeling” to recognize what’s in the mind rather than sinking into it. That yucky feeling has less of a hook when you see it, or feel it in the center of the chest. Some people can feel it physically. It colors everything and becomes the worldview. Now, if I recognize the feeling, I know I can’t trust any thought or assessment that’s coming up because it’s colored by dosa—self-judgment, aversion. So a thought comes: “Oh, I said the wrong thing,” or “They don’t like me,” or “I have nothing to say,” or “They hated my talk.” It may be true or not, but there’s no point in trying to assess the accuracy of the thought because there’s no way I can evaluate it when this lens is on. That’s a huge thing to recognize, and you have to remember it. Sometimes the yucky feeling hits me really strong and I’m lost in it. And I can go, as Ajahn Sumedho says, “Oh, really-lost-in-self-judgment feels like this.” At other times I might notice that it’s coming in as a kind of wilting in the mind. There’s a very subtle tinge to the thoughts before it becomes a strong feeling, you know? It’s like I’m in the supermarket and somebody walks by and I can just have this subtle feeling of “Oh, they’re really cool.” And that has the effect of making me feel down. Why? Because I think I’m not cool? Other times there isn’t that referring back to me. You just walk in a room and whatever happens, happens. Isn’t that nice?

You have a chronic illness—scleroderma. How old were you when you were diagnosed? Thirty-seven. It’s not the most well known of the autoimmune spectrum of rheumatoid diseases. Scleroderma means “hard skin.” When your body makes too much collagen, everything gets hard, beginning with your skin. It can go into your organs, kidney, heart, lungs. At the time, I was having much more severe symptoms. I couldn’t walk well. If I tried to lift my arm, it felt like the skin under my arm was going to rip. And sometimes my hips would just freeze and I couldn’t take another step. Now it’s really receded. You can see I’m pretty fine.

Did your practice help you deal with it? There are a couple of ways the dharma really helped me. The first was in how the mind was relating. Not to the pain—it wasn’t painful so much as really uncomfortable and stiff, and it was difficult to do things. It was more the sense of fear and personal loss at the moment and the fear of future loss and discomfort—that’s where the mind can really go crazy. The other aspect of how the mind was relating was the idea that if you’re sick, your body is manifesting confusion and dukkha. Do you remember all the Louise Hay stuff?

Yes—the idea that the body is manifesting weakness in the mind and you should be able to cure yourself with your thoughts. Yes, exactly. I should be able to heal myself through (continued on page 112) meditation. And if I’m really sick, it’s somatizing. Take the idea of hard skin—maybe I feel I need to be more protected? And then there’s self-blame: If I’m so spiritual, why am I am sick?

I’m sure there are people who still believe they bring on their illness. Yes. And I remember Christopher Titmuss saying, “Give yourself a break, Carol. Look at your family.” My sister had just had a liver transplant. My mom had just had breast cancer. He said, “Genetic stuff happens. Don’t beat yourself up.” And I started thinking about masters like Ramana Maharshi, Ajahn Chah, the 16th Karmapa, and remembering: Oh, right— they all died of disease. But what really helps is to remember that meeting sickness with aversion is just cultivating aversion. My understanding is that awakening happens when the mind is purified. When we’re not clouded with aversion, greed, and delusion, we see the world as it is. And seeing how it is is what liberates us. You don’t have to figure something out—it’s already here. An old Tibetan lama was passing through here one day, and he bonked me on the head and gave me the Medicine Buddha mantra: Tayata om, bekandze bekandze maha bekandze radza samudgate soha [“May the many sentient beings who are sick quickly be freed from sickness. And may all the sickness of beings never rise again”]. I would imagine the Medicine Buddha in white light and say the mantra. I did it with no real wanting and no real investment, and then one day it just flooded over me—a sense of compassion for this body. I realized I had been hating the body for betraying me and bringing aversion. I said, “Ah, it’s like another being, this poor body. It’s suffering and I’m hating it. If you or whoever is next to me were suffering, would I be hating you?” The aversion melted, and there was compassion.

Compassion—the change agent! That was one thing brought on by practice—compassion instead of aversion. The other thing that’s been ongoing is the ability that comes from Vipassana meditation to watch our mind and really know that a thought is a thought. Really know that whatever the content of a thought, whatever emotion may come with it, it’s still just that—thought, energy, emotion. It’s not necessarily true. One day, in the very beginning of the diagnosis, I was leaning down to wash the bathtub, and it was so hard to stretch and move. I was really scared and upset. My mind was like, “Oh my God, I’ll never be able to take another walk. I’ll never be in another relationship”—all of this. And then I saw, “Oh, you don’t have any idea about that. You don’t need to go there.” And that’s the wisdom of seeing, as well as the mental training of our practice to say, Yes, I don’t know. Thoughts are going there, but I don’t have to. I could come back and be with the moment—which wasn’t a pleasant moment. So there’s the training: it’s not just about coming back to pleasant. I was still kneeling, doing the bathtub, and it was uncomfortable. But I could be there: okay, this is how it is now; I don’t have to go into the whole future. And that was a lifesaver. So much of people’s suffering is: this is what’s going to happen, blah, blah, blah. But we never know. We’re always stepping into the unknown. And to trust that and be present with the moment without going into the stories is a lifesaver. I was so grateful to mindfulness, to Vipassana, to mind training for that.

You once quoted Sayadaw U Tejaniya saying that you do this training “not even going for wisdom.” It’s the striving that clouds clear seeing. We say, “If I’m not striving for this, what am I working toward?” As though I create wisdom. No. Where there’s steadiness of moment-to-moment mindfulness in the moment, there’s no greed, hatred, or confusion. As awareness gets its own momentum, an insight will just arise. That wisdom is spontaneous, natural, just an accurate recognition of presence. We don’t have to strive for it. That’s the trust. We do put in effort, but striving for wisdom—when our focus goes there, we’ve stepped out of here. We’ve stepped out of total wakefulness.

I have to come from how it feels right now. If I say that we— the generic “we”—are practicing to free the heart and mind from greed, hatred, and confusion, which is a classical Theravada answer, it happens to be true for me. But when I imagine seeing that in print, we’ve moved into being object-oriented again, which is how we live our whole lives. And that keeps us from knowing if our mind or heart is pure—or colored with wanting. When we see it’s colored with wanting, right then it’s okay: wanting. The mind that’s noticing wanting is clear, is working toward freeing the mind from greed, hatred, and delusion. We’re here to see how the mind works. U Tejaniya says to beginners: We’re here to cultivate a better quality of mind.

Why are you here? Why do you sit? My reason changes all the time, but freedom from greed, hatred, and delusion is a way of describing it. There’s also the piece of being of benefit to all beings. I used to want to really understand what’s the truth, because from the first time I took acid, when I was 16, I’ve felt intuitively that some truth is shot through everything. That’s what motivated me to practice, and now I can see it’s the sense of the cyclical nature of life, of samsara, whether rounds of birth and death, or the birth and death of the sense of self over and over, going nowhere—living fully awake in that understanding. These words tend to use the mind too much, but living from that, in a moment when the heart is really pure and things are just as they are, there really is no problem, even when very painful stuff is happening. A friend of mine calls it the place of no problem. And see—if we watch, wisdom comes. That’s what’s so amazing, so amazing. Because it’s not us making it.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.