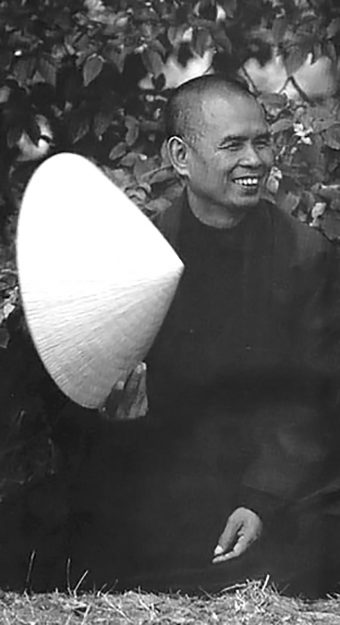

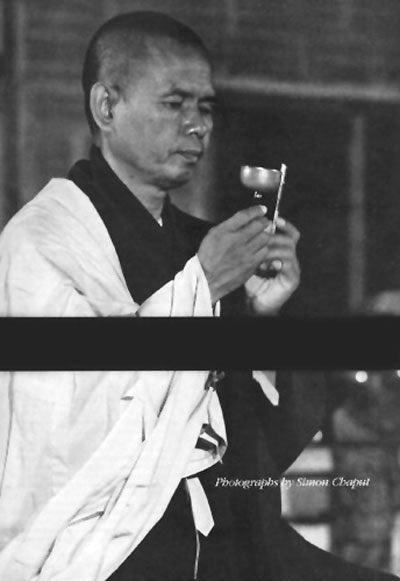

Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh was born in central Vietnam in October 1926 and became a monk at the age of sixteen. During the Vietnam War, he left his monastery and became actively engaged in helping victims of the war and publicly advocating peace. In 1966, he toured the United States at the invitation of the Fellowship of Reconciliation “to describe the aspirations and the agony of the voiceless masses of the Vietnamese people.” As a result, he was threatened with arrest in Vietnam and unable to return. He served as the chairman of the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation during the war and in 1967 was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Over the years, Thich Nhat Hanh has made efforts to help Vietnamese children affected by the war and to ensure the safety of boat people. For the past several years he has been leading mindfulness retreats for American Vietnam War veterans, psychotherapists, environmentalists, social-change activists, and many others.

He lives in exile now in Plum Village, a retreat center in southern France where he teaches, writes, gardens, and works to help refugees. He is the author of over sixty books, including Call Me by My True Names, Being Peace, and Old Path, White Clouds: Walking in the Footsteps of the Buddha (Parallax Press). His forthcoming book, Living Buddha, Living Christ, will be published by Riverhead Books in September. This interview was conducted by Helen Tworkov in Plum Village in February 1995.

***

Tricycle: Hundreds of thousands of people are in touch with Buddhism only through you. What is important for them to know?

Thich Nhat Hanh: [Laughing] To know about Buddhism—or to know about themselves? It is important that we understand that Buddhism is a way of life. People may be interested in learning about Buddhism because they have had some difficulties with their own religion. But for me, Buddhism is a very old, broad tradition. It is part of the heritage of humankind, and if you don’t know what it is, you don’t profit from its wisdom.

Tricycle: Can everyone benefit?

Thich Nhat Hanh: Buddhism is more of a way of life than a religion. It is like a fruit. You may like a number of fruits, like bananas, oranges, mandarins, and so on. You are committed to eating these fruits. But then someone tells you that there is a fruit called mango and it would be wonderful for you to try that fruit. It will be a pity if you don’t know what a mango is. But eating a mango does not require you to abandon your habit of eating oranges. Why not try it? You may like it a lot. Buddhism is a kind of mango, you see—a way of life, an experience that is worth trying. It is open for everyone. You can continue to be a Jew or a Catholic while enjoying Buddhism. I think that’s a wonderful thing.

Tricycle: Originally, in your book Interbeing, you published the Fourteen Precepts for the first time. I’m curious about the transition from those fourteen to the five that you have been emphasizing more recently. It seems that the five are perhaps more disciplined. Is that because of your perception of your students, that we need more discipline?

Thich Nhat Hanh: The five precepts are very old and date back to the time of the Buddha. But we feel that they should be rephrased; represented again in a way that can be understood more easily for the people, especially the young in the West. If you say, “Don’t do this, don’t do that,” people don’t like that. They feel they are being forced to do something. In Asia we also profit from that rewording of the five precepts, because Asia is now in touch with the West and Westernized in their daily life.

Tricycle: What is the practice of the precepts?

Thich Nhat Hanh: To practice the precepts is to protect yourself and to protect people you love; to protect society. That is why “Compassion” is the first precept, instead of “Do not Kill.” It is worded like this because it is a practice of protecting life. I vow to refrain from killing, from encouraging people to kill. I vow to do whatever I can in order to protect life and to prevent the killing, not only with my body, with my speech, but also with my way of life, with my thinking. By practicing awareness, mindfulness, you know that suffering is born from the destruction of life. People are ready to accept this as a guideline of their life. And the same is true with the other four precepts.

Tricycle: You said “to protect yourself and to protect your family.” What did you mean exactly?

Thich Nhat Hanh: I’m using everyday language. When you practice not drinking alcohol, you not only protect yourself, you protect your family, your husband, your wife, your children—you protect your society. If you don’t get drunk while driving, you protect people—not only yourself, but your family, too. If you die in an accident, your family will have to suffer. And you protect the person who you might injure just by your practice of not drinking. It’s very simple.

Related: Five Precepts of Buddhism Explained

Tricycle: Can you explain what you mean when you talk about “ancestors” or “heritage” with regard to karma? There’s a sense that what we call “karma” is somehow genetic, biological, is within genetic transmission.

Thich Nhat Hanh: Karma is action, and action of the father can affect the children. When you practice, you transform the karma. You practice like that not only for “your” transformation but the transformation of your parents, your ancestors. In Vietnam there is a saying that when the father eats too much salt, the son has to drink a lot of water. Karma, or action, is like that. Not only do you have to suffer, your children have to suffer also. That is why to practice the precepts is to protect yourself and to protect future generations.

Tricycle: Is this idea of genetic lineage compatible with reincarnation?

Thich Nhat Hanh: I can only smile. Reincarnation means that there is something to enter into the body. That something might be called the “soul,” or “consciousness,” whatever name you might like to use. Re means again—reincarnation means “into the body again.” The understanding is that the “soul” can go out and “you” can be gone into. Maybe it’s not the best word, not a very Buddhist word. In Buddhism there is the word rebirth or reborn, and then the basic teaching of the Buddha is “no-self.” Everything manifests itself because of conditions. If there is no body, our perceptions, our feelings, and our consciousness cannot be manifested.

Tricycle: Not born, but manifested?

Thich Nhat Hanh: Yes. So, body is one condition. There are many other conditions. There are at least two kinds of Buddhism; popular Buddhism and deep Buddhism. Which kind of Buddhism you’re talking about is very important. It requires learning and practice, because anything you say in the second may be misunderstood and can create damage. The true teaching is the kind of teaching that conforms to two things: First, it is consistent with the Buddhist insight. And secondly, it is appropriate for the person who is receiving it. It’s like medicine. It has to be true medicine, and it must fit the person who is receiving it. Sometimes you can give someone a very expensive treatment, but they still die. That is why when the Buddha meets someone and offers the teaching, he has to know that person in order to be able to offer the appropriate teaching. Even if the teaching is very valuable, if you don’t make it appropriate to the person, it is not Buddhist teaching. To some other people, it is excellent teaching. But, to this person, it’s not Buddhist teaching because it does damage, does more damage than good. If you offer the things that are not appropriate, you destroy people.

Tricycle: At what level are you addressing the thousands of people reading your books?

Thich Nhat Hanh: Most of these books have a specific kind of audience or readers. Being Peace, for example, was first spoken to children and to people who come for a retreat. When you read the book, you can see what kind of audience the book is intended for. That should be true of everything, every sutra, or the Bible. When Jesus Christ talked to someone, he had to know and to talk to that particular person. The same is true with the sutras. You have to know who the Buddha is speaking to. Maybe the Buddha is not speaking to you. He’s speaking to another person. But if you know what the Buddha is speaking to in that person, the Buddha can speak to you also. This is very important.

Tricycle: Is there a problem with making teachings appropriate for so many, many people in the West who have no Buddhist background at all?

Thich Nhat Hanh: We all have to examine the problem of appropriateness of the teaching, because it is a big problem. As I said, the five precepts had been presented in China and Vietnam and Tibet for a long time, just as they were—there was no problem with the wording [Laughing]. But when we present them to the young people here, they say “I don’t like to be ordered around.”

Tricycle: How has living your life affected the way you present the teachings? Has the importance of things shifted over time in terms of how you say it, or what you say, or what you feel the world needs to know?

Thich Nhat Hanh: In Plum Village, Vietnamese refugees come to study and practice alongside Europeans and Americans. During the summer opening, I used to give dharma talks in three languages: Vietnamese, French, and English. Our Western friends were very curious about the dharma talks I gave in Vietnamese. They came and listened to the translation with earphones and realized that when I give a teaching in Vietnamese, it’s quite different. I am aware that I’m addressing people with a background of a particular kind of suffering. Their suffering is not exactly the same kind of suffering which Westerners have had to undergo.

Tricycle: Can you speak about the difference?

Thich Nhat Hanh: Suppose we were talking about a family of refugees that had undergone suffering as boat people. They might have people dying during the dangerous trip. Sometimes a child is alive, and his or her parents are dead. They have suffered the loss of a loved one, but the circumstances are different.

So I had the impression that dharma talks given to the Vietnamese would feel a little strange to Westerners. But in fact, from time to time, Western friends say, “Why don’t you talk to us about the same problems?” And the same is true of the Vietnamese—each is curious what I tell the other. It turns out that there are things that are common to both cultures, and each profits from the other’s teaching.

Tricycle: Can awakening be realized through mindful breathing—which seems to be at the heart of all your teaching?

Thich Nhat Hanh: Of course. Mindful breathing helps you see your anger, your frustration, your suffering. When you breathe mindfully, you practice looking deeply into yourself. You are made of feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness. Your true nature is what—if not these things? Because it is wrong perceptions that make you suffer, and if you don’t know the nature of your own perceptions, you are not likely to get free of your suffering. So your true nature is the nature of your feelings, your perceptions, your mental formations, and your consciousness.

True nature does not point to something abstract, but to your nature as the nature of the One. If, while practicing meditation, you ignore the presence of social injustice and the fact that people are dying every day, you are not looking at your true nature because all of this is the manifestation of our collective consciousness, our true nature.

Tricycle: So much of your teachings seems to be about behavior.

Thich Nhat Hanh: Why don’t you say “daily life,” or “being in the moment and responding to what is there”?

Tricycle: Well, for example, you talk a lot about being happy, as if creating happiness in a very deliberate way is itself beneficial, whereas so much of “daily life” seems to be about anger, frustration, despair.

Thich Nhat Hanh: I have noticed that people are dealing too much with the negative, with what is wrong. They do not touch enough on what is not wrong—it’s the same as some psychotherapists. Why not try the other way, to look into the patient and to see positive things, to just touch those things and make them bloom?

Waking up in the morning, you can recognize “I’m alive” and that there are twenty-four hours for me to live, to learn how to look at living beings with the eyes of compassion. If you are aware that you are alive, that you have twenty-four hours to create new joy, this would be enough to make yourself happy and the people around you happy. This is a practice of happiness.

Tricycle: It’s very hard to imagine that somebody could come out of Vietnam, the way you did, and be completely free of anger. Do you think of yourself as being free from anger?

Thich Nhat Hanh: You have to practice in order to diminish your anger, to help non-anger prevail. Non-anger is a wholesome mental formation that you can touch. When you have seen your whole country destroyed, millions of people dying, it’s natural that you get angry. But through the practice of looking deeply, you can see things that other people cannot see. You can see that the American soldiers were very scared too, and because of this they dropped lots of bombs. They didn’t know what happened down there when a bomb exploded.

If you practice looking deeply, you ask, Why have they come here? Have they come with intention to kill? To destroy our country? If you had had any contact with the soldiers, you would see that they had been sent in order to kill or to be killed, and that the Vietnamese soldiers also don’t want to be killed, don’t want to kill, but are forced to do so. When you practice looking like that, you see that the deep cause of the war is a policy that is based on a wrong perception of the situation—in Vietnam and in the world—and wrong perception is the real criminal.

Tricycle: Do you still get angry about things, whether it’s about the war from thirty years ago or about contemporary things? Do you still have to practice dissolving anger?

Thich Nhat Hanh: The seeds of anger are always there. But when you notice, when you keep alive your understanding, they have no chance to manifest. Understanding is something that stays with you, and practicing the precepts, practicing meditation, helps you deepen your understanding all the time.

You know in Vietnam, when you sat during the war, when you sat in the meditation hall and heard the bombs falling, you had to be aware that the bombs are falling and people are dying. That is part of the practice. Meditation means to be aware of what is happening in the present moment—to your body, to your feelings, to your environment. But if you see and if you don’t do anything, where is your awareness? Then where would your enlightenment be? Your compassion? In order not to get lost, you have to be able to continue the practice there, in the midst of all that. But no one can be completely there twenty-four hours a day. I find that after having talked to two or three people who have deep suffering, I, myself feel the need to withdraw in order to recuperate.

Tricycle: You have become so popular that I have heard people say “Thich Nhat Hanh is a movement, not a teacher.”

Thich Nhat Hanh: That’s not my impression. I see myself as a very lazy teacher, as a very lazy monk.

Tricycle: I don’t think very many people see you that way.

Thich Nhat Hanh: I have a lot of time for myself. And that’s not easy. My nature is that I don’t like to disappoint people, and it is very difficult for me to say no to invitations. But, I have learned to know my limit, learned to say no and to withdraw to my hermitage to have time for my walking meditation, my sitting, my time with the garden, with the flowers and things like that. I have not used the telephone for the last twenty-five years.

My schedule is free. It is a privilege. Sometimes I remember a Catholic father in Holland who keeps a beeper. I asked him, “Why do you have to keep that?” and he said “I have no right to be disconnected from my people.” Well, in that case, you need an assistant. Because you cannot continue to be of help to other people if you do not take care of yourself. Your solidity, your freedom, your happiness, are crucial for other people. Taking good care of yourself is very important. I have learned to protect myself. That does not mean that I have to be unkind to people, but sharing the teaching with helping professionals, well, I always say, “You work so hard. Doctors and nurses and social workers, you work too hard. And if you face so much stress, you cannot go on, you have burned out. So please find ways—by all means—in order to protect yourself. Come together and discuss strategies of self-protection. Otherwise you cannot help people for a long time.” Because I urge other people to do so, I do so myself.

Tricycle: You are often called the “father of engaged Buddhism.” But there is concern that the engaged Buddhist movement in the United States is very different from what you’re talking about for your own life, that people don’t come back to protecting themselves through their practice enough. There seems to be some confusion around your work with regard to this; the ideal that is sometimes projected in the West is that social action is practice, but this has been used as a way of replacing contemplative forms of practice with social action.

Thich Nhat Hanh: Well, in a difficult situation like the situation of war, you cannot dissociate yourself from a society that suffers. You have to be engaged and to do whatever you can in order to help. Everyone is capable of having time to sit, to walk, to eat mindfully, to eat silently or alone or with the sangha. If you abandon basic things like that, how can you call yourself a practicing Buddhist? If you are smart, you find a lot of time to practice during your day, even cooking your dinner or preparing a pot of tea. There’s no boundary between practice and non-practice.

For those who only talk about it, I have nothing much to offer. But for those who really want to practice, I would say that it is possible to practice meditation the whole day. Even if I am only taking three steps or five steps, I always practice walking meditation. I do it, I don’t just say it. Even during a one-hundred-day trip in North America, the most difficult environment for practice, I have done that.

Tricycle: North America is the most difficult environment for practice?

Thich Nhat Hanh: Yes, because it’s so busy, people are so quick. During that one hundred days of teaching retreats and dharma talks, I always followed my breathing. I always practice walking meditation, even at the airport.

Related: Give Yourself a Breathing Room

Tricycle: What is the difference between three steps of mindful walking and three steps of not mindful walking?

Thich Nhat Hanh: Mindful walking is walking in such a way that you know you are walking. You are aware of every step. There is solidity, mindfulness, the awareness that you are alive—it is you who are walking, not a ghost walking. You are completely alive. You walk not only to arrive somewhere, but to be entirely present in every step you make.

Tricycle: Is it possible that engaged Buddhism in North America is being used in the United States to create a more diluted Buddhism, or what some people call “Buddhism Lite”?

Thich Nhat Hanh: I think everything is possible. Anything can turn out to be like that. If you practice, that’s all right. The question is whether people practice enough. Engaged Buddhism is engaged because you are urged and encouraged to do sitting meditation to produce joy and stability, for yourself and for the people around you.

I sometimes say, “Sit for your father. Sit for your mother. Sit for your sister. Sit for me.” Because when you sit like that you get the joy, the stability, and all your ancestors in you get the joy and the stability. If I, your teacher, am sick that day, you sit for me also, because from the outcome of your sitting, we all profit. So sitting silently in the meditation hall, alone or with the sangha, is already engaged Buddhism. When you smile, that is engaged Buddhism, because smiling like that is to relax and to bring joy. When you smile, all your ancestors smile with you; your children and grandchildren also. And, if you can be smiling, you are building your sangha with your smile.

A smiling person is very crucial for the sangha. When a smiling person comes to visit your sangha, very fresh, very pleasant, you should beg her to stay, beg him to stay, because that is a plus to the sangha. The happiness of a person is very important to the world. That is why engaged Buddhism means that you practice sitting meditation or walking meditation in the monastery not only for your so-called “self,” but you do it wherever you are and for the whole society.

Tricycle: In the United States, many people now talk about “engaged Buddhism” as if it replicates a Christian sense of charity, a sense that you are “engaged” if you’re working with homeless people, if you’re working with AIDS projects.

Thich Nhat Hanh: I think that we need dharma teachers to help explain more about engaged Buddhism. One of the things I have been trying to do is to urge people to set up sanghas. There is a kind of practice we call “sangha building.” Sangha building is so crucial. If you are without a sangha, you lose your practice very soon. In our tradition we say that without the sangha you are like a tiger that has left his mountain and gone to the lowland—he will be caught and killed by humans. If you practice without sangha you are abandoning your practice.

Whether you are a psychotherapist, a doctor, a nurse, a social worker, whoever you are, you can only survive as a practitioner if you have a sangha. So, building a sangha is the first thing you have to do. That is what we always urge in retreats. On the last day of every retreat we organize sangha-building sessions. We say that the first thing you should do when you go home after retreat is to build a sangha for the practice to be able to continue. If you are surrounded by a sangha, you have the chance to sit together, to walk together, to learn together, and you won’t lose your practice. Otherwise, in just a few weeks or few months, you will be carried away and you can no longer talk about practice—engaged or not engaged. No practice at all. Although I speak about engaged Buddhism, I still live like a monastic, and I feel very engaged. I don’t feel disconnected with anyone.

The Fourteen Precepts of the Order of Interbeing

1. Do not be idolatrous about or bound to any doctrine, theory, or ideology, even Buddhist ones. Buddhist systems of thought are guiding means; they are not absolute truth.

2. Do not think the knowledge you presently possess is changeless, absolute truth. Avoid being narrow-minded and bound to present views. Learn and practice non-attachment from views in order to be open to receive others’ viewpoints. Truth is found in life and not merely in conceptual knowledge. Be ready to learn throughout your entire life and to observe reality in yourself and in the world at all times.

3. Do not force others, including children, by any means whatsoever, to adopt your views, whether by authority, threat, money, propaganda, or even education. However, through compassionate dialogue, help others renounce fanaticism and narrowness.

4. Do not avoid contact with suffering or close your eyes before suffering. Do not lose awareness of the existence of suffering in the life of the world. Find ways to be with those who are suffering, including personal contact, visits, images, and sounds. By such means, awaken yourself and others to the reality of suffering in the world.

5. Do not accumulate wealth while millions are hungry. Do not take as the aim of your life fame, profit, wealth, or sensual pleasure. Live simply and share time, energy, and material resources with those who are in need.

6. Do not maintain anger or hatred. Learn to penetrate and transform them when they are still seeds in your consciousness. As soon as they arise, turn your attention to your breath in order to see and understand the nature of your anger and hatred and the nature of the persons who have caused your anger and hatred.

7. Do not lose yourself in dispersion and in your surroundings. Practice mindful breathing to come back to what is happening in the present moment. Be in touch with what is wondrous, refreshing, and healing both inside and around you. Plant seeds of joy, peace, and understanding in yourself in order to facilitate the work of transformation in the depths of your consciousness.

8. Do not utter words that can create discord and cause the community to break. Make every effort to reconcile and resolve all conflicts, however small.

9. Do not say untruthful things for the sake of personal interest or to impress people. Do not utter words that cause division and hatred. Do not spread news that you do not know to be certain. Do not criticize or condemn things of which you are not sure. Always speak truthfully and constructively. Have the courage to speak out about situations of injustice, even when doing so may threaten your own safety.

10. Do not use the Buddhist community for personal gain or profit, or transform your community into a political party. A religious community, however, should take a clear stand against oppression and injustice and should strive to change the situation without engaging in partisan conflicts.

11. Do not live with a vocation that is harmful to humans and nature. Do not invest in companies that deprive others of their chance to live. Select a vocation that helps realize your ideal of compassion.

12. Do not kill. Do not let others kill. Find whatever means possible to protect life and prevent war.

13. Possess nothing that should belong to others. Respect the property of others, but prevent others from profiting from human suffering or the suffering of other species on Earth.

14. Do not mistreat your body. Learn to handle it with respect. Do not look on your body only as an instrument. Preserve vital energies (sexual, breath, spirit) for the realization of the Way. (For brothers and sisters who are not monks and nuns:) Sexual expression should not take place without love and a long-term commitment. In sexual relationships, be aware of future suffering that may be caused. To preserve the happiness of others, respect the rights and commitments of others. Be fully aware of the responsibility of bringing new lives into the world. Meditate on the world into which you are bringing new beings.

♦

Excerpted from Interbeing: Fourteen Guidelines for Engaged Buddhism, with permission from Parallax Press.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.