What am I afraid of? You name it. There’s the existential fear of untimely death, or of sudden, unforeseen abandonment. Then there are the more banal fears of financial ruin and loud noises. Statistics and my clinical experience suggest that I’m not alone. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, 19 million Americans suffer from chronic fear-related disorders. It seems we’re living in a time of pervasive fear: of the enemy within, of destructive leaders at the helm, of disease and other crises brought on by our suffering and neglected planet.

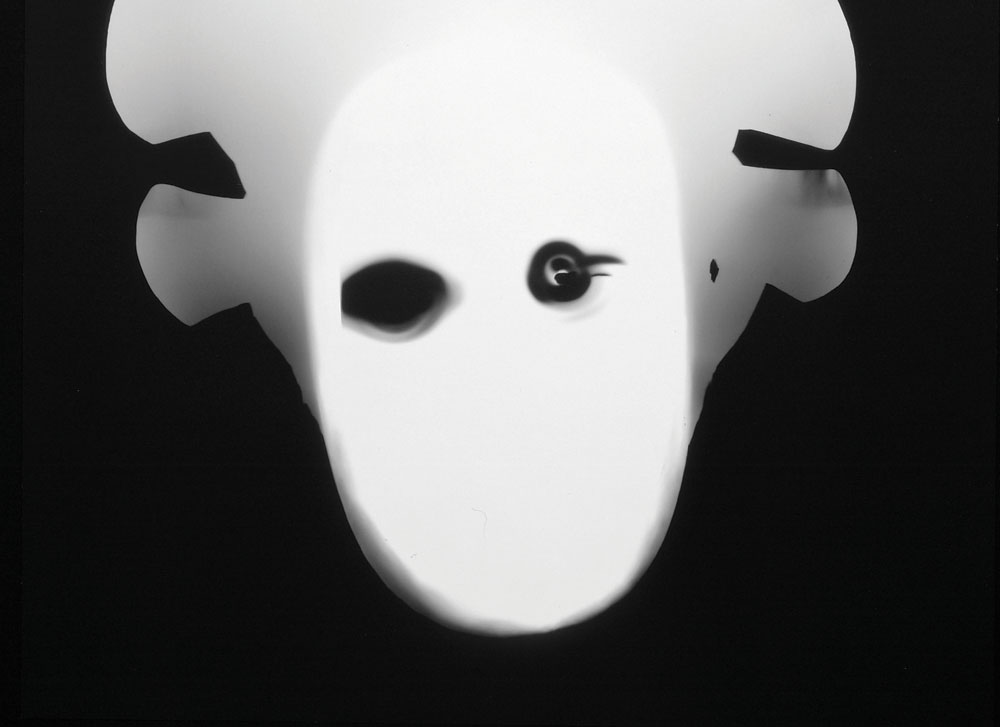

As a psychoanalyst, I spend much of my day mapping out people’s fears. We learn early in life to be afraid of anything that has caused us pain. In its healthiest form, this is a good way to ensure our survival and create the conditions necessary for safety and well-being. The Buddha himself described different types of fear: the useful kind that prepares us to take skillful action and reduce harm, and the kind that makes us see a cobra where a piece of rope has cast its shadow.

But what if we have been unable to ward off pain, either because of circumstances beyond our control, or because we have not yet learned how to protect the mind when necessary? In this scenario, fear can slip into anxiety, a feeling known by anyone who has been unsafe for extended periods of time. Fear and anxiety are not the same, although they are often connected. Fear is a signal that we are about to face an imminent and knowable threat; it alerts our body and nervous system to danger. An approaching tornado, for instance, will induce a powerful and physiological response: we need to mobilize in order to survive. Anxiety, by contrast, is a response to a future threat or inner conflict. It is a feeling of dread that something unwanted may be coming, but when and how remain unknowable and beyond one’s control.

When we have been badly hurt, the fear of yet more pain catalyzes anxiety. And living with this comingling of fear and anxiety makes it hard to figure out what’s a rope and what’s a snake. Our thinking gets fuzzy as our feelings run too high.

All emotions, including fear, are multitiered, with a psychological, a physiological, and a behavioral component. For some of us, frightening situations make us want to find our loved ones and hold on tight. For others, fear shunts us into isolation, where we may try to protect ourselves from residual feelings of shame, if not from the source of fear itself.

Of course, humans, like all animals, have strong physiological responses to fear. When we are afraid, the amygdala, a small organ in the center of the brain, immediately sends a signal to the autonomic nervous system. This is what spurs an increased ability to run like hell or fight like an alley cat or, if necessary, to play dead until the threat has passed. When we feel fear, we have either an active or passive response. An active response comes from the sympathetic nervous system, which generates the fight-or-flight response. The passive response comes from the parasympathetic system, which generates the extremes of freeze or faint.

A Buddhist perspective on fear, and the practices that address it, can offer an extraordinary antidote to these habituated reactions. According to the Abhidharma, the primary texts on Buddhist psychology [see this issue’s interview about the Abhidharma, “Mapping Your Mind: The Original Buddhist Psychology”], fear is not inherent in what is known as main or basic mind. What is inherent? Clear seeing, spaciousness, pure awareness. All feelings come and go, and are by their nature ephemeral. But if we don’t train our minds to see that, we end up riding life like the old roller coaster at Coney Island that threatened to hurl people from their seats every now and again. The great Buddhist teachers throughout history have shown by example that when we cultivate that basic aspect of mind, the way we experience feelings will change.

I recently saw a documentary by the film director Mickey Lemle called The Last Dalai Lama? In one scene, His Holiness looks into the camera and says: “Basically, I think I’m short-tempered. If something goes wrong, reaction is immediately to say, ‘Oh, shouting!’ But then, very fast, it’s over. Completely gone.” When meditators are subjected to painful stimuli—an experience likely to provoke fear and anger—they have the same physiological response as everyone else. But unlike non-meditators, who continue to show increasing signs of distress, these yogis return to a baseline of equanimity almost immediately. This is compelling evidence that meditation is no indulgence. It’s potentially life-changing and, in the right circumstances, life-saving. It helps us to stop identifying with strong feelings such as fear and anger so that we can quickly recover our ability to feel safe and act accordingly.

When most people experience acute fear, the mind gets fuzzy as the blood flows from the brain to the limbs. This is a critical deficit just when we most need to be discerning. But if the nervous system is trained to recover, we’re much better able to keep cool, breathe, and think things through. No fainting, no fleeing, no slapping necessary.

Think about what you fear. As you contemplate the answer, keep breathing, slowly, deeply. The next time you feel afraid, your fears may be strong and real. They may be a response to intense pain. But deep within the body-mind system, there is a reliable and fast-acting remedy. Whether you call it buddhanature, clear seeing, inner strength, or simply a regulated nervous system, the right medicine is available. And then, very fast, it will be over.

In the following special section, our contributors discuss their own experiences with fear and the Buddhist teachings and practices they have used to transform the various grips of fear. Ranging from Dharmavidya David Brazier, a teacher in the Pure Land tradition, to Marcela Clavijo, a Tibetan Buddhist nun and Iyengar Yoga teacher, to Kim Larrabee, an early childhood specialist and Theravada practitioner, teachers and students describe their own painful struggles with being afraid, how it has shaped their practice, and what has helped them. Fear is at the root of so much suffering. Hopefully these essays and teachings will be encouragement for us all to loosen and dissolve those roots, and reap the blessing of release.

Special Section

“The Gift of Fear” by Dharmavidya David Brazier

“Learning to Speak the Truth” by Daisy Hernández

“Drowning on My Cushion” by Kim Larrabee

“What Green Tara Can Teach Us about Fear” by Marcela Clavijo

“A Safe Container for Fear” by Josh Korda

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.