THE SRI LANKAN VILLAGE where the Theravadin Buddhist nun P. G. Ranwala built her temple is in the upcountry, miles from any city. One-story mud-and-thatch houses painted pastel pink, blue, and green, and deeply ridged paddy fields carved into the mountainside below give the village a prosperous feeling, although the people here live on the edge of poverty. Before Ranwala came, the villagers waited weeks for monks to come from the city of Kandy to perform chanting ceremonies and other Buddhist rituals on their behalf. Most parents relied on weekly radio programs to provide religious education to their children.

Now the center of community life and spiritual practice is the temple built by the 56-year-old former English teacher who left her career, her husband, and her own village to become a Buddhist nun. Ranwala died soon after the temple was built, but the children learn about Buddhism in weekly Sunday school classes from the nuns who run the temple now. They regale them with jataka stories of Buddha’s past lives when he was a rabbit, a monkey, and other characters. The nuns’ days are busy with ceremonies for villagers who are about to embark on a new venture for those who are ailing.

Ranwala’s achievement is all the more extraordinary in light of the fact that Buddhist nuns in Sri Lankan society are barely seen as legitimate spiritual seekers in the eyes of the Buddhist religious establishment there. During the Buddha’s lifetime, men and women were both well supported in the ascetic life by laypeople. Nuns had an active community, thebhikkshuni sangha, and women of every age and social caste became nuns. Alongside the monks, they were teachers, meditators, community activists, and leaders. But when Sri Lanka was invaded in 1017 by lndia, the Sri Lankanbhikkshuni sangha was disbanded. Nevertheless, Sinhalese women continued to choose a spiritual life by renouncing their worldly ties, donning robes and living as bhikkshunis. Today, there are six thousand women registered with the government as nuns, or dasasilmanyos. But without a sangha, the women have had to contend with discrimination, harassment, and extreme poverty. Most are disregarded and slandered, and some are even threatened by none other than the monks.

ln Theravada Buddhism (the foremost religion in Southeast Asia), the ideal for those who want to pursue a spiritual path is to give up their worldly possessions, their homes, and their names; shave their heads; don orange-colored robes; and become monks or nuns. This tradition of monastic life was established by the Buddha himself, who laid out hundreds of rules that monks and nuns agreed to follow in a ritual of ordination. Some of the rules include not handling money; not cooking their own food; remaining celibate; owning no more than a few robes, a bowl and needle and thread; and not harming any beings (even insects). The idea was to create a minimalist lifestyle so that ascetics would not be distracted from meditation and their ultimate goal: attaining enlightenment. The ascetics were supported by the generosity of laypeople who, in Buddhist countries, still feed and clothe them. ln the Buddhist worldview giving alms—especially to monks and nuns—means that the donor accrues merit (good karma), which is key to ensuring a better rebirth in the next life.

Today, many Sri Lankans believe that the bhikkshusangha (monk’s community) has become corrupt, with many monks blatantly flouting their vows of poverty by owning fleets of Mercedes and having large bank accounts and servants. The government supports them generously, so that all monks have access to a special educational system and libraries far superior to what most Sri Lankans enjoy. Despite their wealth and privilege, many powerful Sri Lankan monks believe that the reestablishment of the bhikkshuni sangha threatens their well-being, because the monks would have to share their government funding and lay support with women. As of today, the government doesn’t provide any direct financial assistance to nuns. Many of these monks have been undermining what meager support exists for nuns by teaching laypeople that giving to monks leads to more merit than giving to nuns. Some say the nuns are not truly spiritual but only looking for free handouts. Even nuns who attend the universities find themselves harassed by some monks on the faculty who don’t consider it “proper” for nuns to study Buddhist texts. Two years ago an influential monk counseled the Sri Lankan government not to allow the international Buddhist women’s group, The Daughters of the Buddha, to hold their 1993 conference in Sri Lanka unless the attendees vowed not to mention the words “higher ordination,” a term referring to the ritual that would elevate a dasasilmanyo to a bhikkshuni, making her equal to a monk. Many of the nuns take a characteristically Buddhist view of this harassment and say that the patriarchal forces set against them by these monks stem from fear and greed—two fundamental states of mind that the Buddha taught lead to suffering. Therefore, these nuns say, they don’t take the attacks personally; some even feel compassion—a higher Buddhist virtue—for the monks who are mired in this mental hell.

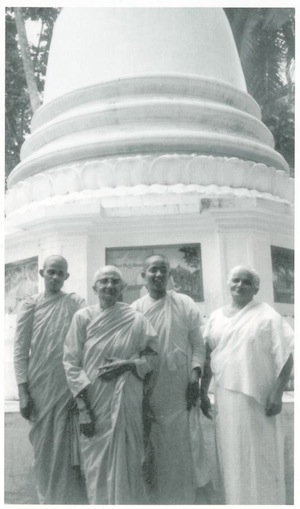

Although no longer permitted the prestigious higher ordination ceremony the monks undergo, the nuns still shave their heads, wear the robes, and vow to follow the ten precepts designed to help them cultivate Buddhist virtues of selflessness, lovingkindness, and equanimity. Despite the few resources they have, a great many have managed to create spiritually fulfilling lives for themselves. Some nuns live in village temples; others live in the innercity slums of Colombo, in crowded aramayas (convents), often without electricity and plumbing. One woman became a nun at age 70. She made it her job to teach the children, some of whom were near starvation, how to meditate. Some have devoted their lives to meditation and live in Sri Lanka’s few meditation centers. Still others live in small, cramped outbuildings around monasteries in up-country villages, cooking and cleaning for the monks and occasionally receiving lessons about Buddhism. One group of these nuns are all young women from the same village who were drawn to the stories they had heard from an eloquent monk about Buddhist enlightenment. Yet, having no nuns for role models, hearing no stories about the bhikkshuni sangha that once existed, these nuns suffer from low self-esteem and a sense of futility. One nun, age 17, confided that she had become a nun “even though I know l can never be an ‘enlightened one,’ since I am just a woman.”

It is this core belief that a new group of nuns in Sri Lanka wants to eradicate. They have created the Bhikkshuni Foundation, an organization devoted to educating Buddhist nuns not only about Buddhist philosophy and meditation but also about the way sexism has influenced their own beliefs about their capacity to become fully enlightened in the Buddhist tradition. Although there have been a few charismatic nuns who have emerged as respected teachers in Sri Lanka over the years, few have challenged the monks’ authority or the sexism of the monastic order. The nuns of the Bhikkshuni Foundation , on the other hand , believe it is essential for the nuns to have a revolution within as well as without. “Some of the older nuns say they hope to be reborn as monks in their next life,” said one young nun, “but we say it’s not our karma to be kept down like this.”

“One way they have tried to keep nuns here quiet is to keep us ignorant,” says Daya Kusum, a 24-year-old nun and one of the organizers of the Bhikkshuni Foundation. ‘The older nuns have internalized the idea that nuns should not know too much, and they have passed this on to the younger nuns. We are focusing our efforts on reversing this.” Using the wordbhikkshuni in their organization’s name is in itself a radical act, because the word signifies that a nun is equal to a monk. Certain monks in the country have expressed their outrage at this hubris. One much-respected monk claimed that helping nuns was “not necessary. Those women should stay home and hope for a better rebirth in their next life.” A “better rebirth,” in his mind meant birth as a male.

The biggest loss the nuns express concerns their lack of Buddhist education. They know only the most rudimentary aspects of Buddhist philosophy and meditation, and few monks have been willing to reach them. Although some monks have attempted to thwart the efforts of the Bhikkshuni Foundation, tying up the nuns’ funds and kicking them out of the temple where classes had been held, it continues to grow.

Surprisingly, the thing the monks most fear—that the nuns of Sri Lanka will demand higher ordination—is not important to most nuns, says Daya Kusum. “It is only a ritual. Look at the monks: they have it, and it only increases their pride and feelings of superiority. So maybe we are better off without it.”

In fact, some of the nuns are rethinking the whole concept of a “legitimate”bhikkshuni sangha. One recounted her own version of the story of how nuns first came to receive higher ordination. “When the Buddha went from town to town in India reaching the dharma, the men became so inspired that they left home to follow him and join the sangha. The women saw this and they said among themselves, ‘We, too, crave to learn more about the dharma and achieve nirvana. We must also go to the Buddha and learn.’ So they marched off to where Buddha was spending the win ter. It was a difficult journey, and many of the women became sick, or their feet were bruised by the rocky ground, so other women carried them and took care of them. By the time they arrived at the Buddha’s encampment, not a single woman had been lost or left behind.

“But when they approached the Buddha and asked that he allow them to receive higher ordination and become abhihkshuni sangha, the monks objected loudly. Buddha listened to them and told the women he had to respect the word of his monks. The women—including the Buddha’s own stepmother—sat down in front of his tent and refused to leave. They had walked a long way and they were not about to give up. Impressed with their persistence, the Buddha agreed to ordain them.”

The young nun paused, and then said, “But it wouldn’t have mattered if the Buddha had ordained us or not. In our hearts, we were already a community. We were already on the path to enlightenment.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.