Fear is perfectly natural, with its roots lying deep in the survival instinct. All living beings, from the simplest amoeba to some of the most realized beings on the planet, will have some form of aversive reaction to external threats.

A few years ago, I just happened to be on the same eighteen-seat plane as the Dalai Lama, flying from Dharamsala to New Delhi, a route where the updrafts from the Himalayan foothills can be vicious. In his autobiography, His Holiness talks about his fear of flying, and every time I glanced back at him on this particular flight he was visibly anxious, staring intently out of the window while fingering his mala and silently reciting a mantra. Just the fact that the Dalai Lama was on the plane made me feel safer, but seeing his nervousness was also somehow comforting, making my own fear of flying seem less personal.

Becoming more comfortable with fear begins with our acknowledgment that these strong sensations we feel are a biologically programmed reaction to some perceived threat. The Buddha called all such organic reactions “underlying tendencies” and said that the way to work with them is to realize, “This is not mine. This I am not. This is not my self.” If we understand fear as an evolved survival mechanism, we gain some perspective and perhaps some release from our identification with the feeling. We might even arrive at a place where we can bow down to fear, seeing it as a friend who is looking our for our very life. But a caveat here: Becoming too comfortable with your fear could be hazardous to your health. If the wolf is at the door, it is wise to listen to your fear and refuse to open up.

Becoming more comfortable with fear begins with our acknowledgment that these strong sensations we feel are a biologically programmed reaction to some perceived threat. The Buddha called all such organic reactions “underlying tendencies” and said that the way to work with them is to realize, “This is not mine. This I am not. This is not my self.” If we understand fear as an evolved survival mechanism, we gain some perspective and perhaps some release from our identification with the feeling. We might even arrive at a place where we can bow down to fear, seeing it as a friend who is looking our for our very life. But a caveat here: Becoming too comfortable with your fear could be hazardous to your health. If the wolf is at the door, it is wise to listen to your fear and refuse to open up.

When feelings of fear, sadness, or anger arise in me, as they have more regularly since September 11, my practice is to bring awareness to the sensations in my body, and say to myself what has become almost a mantra for me, “It’s perfectly natural.” Another phrase that I use is “I’m only human.” (Some people think the phrases work better as “It’s only natural,” and “I’m perfectly human.”) Often the physical sensations will remain, or they may begin to move and change, but whatever they do, my sense of self is no longer so tightly contracted around them. Recognizing that difficult emotions are common to all humans also seems to arouse immediate feelings of empathy with others. We share our emotions: they are part of our collective karma, the human condition.

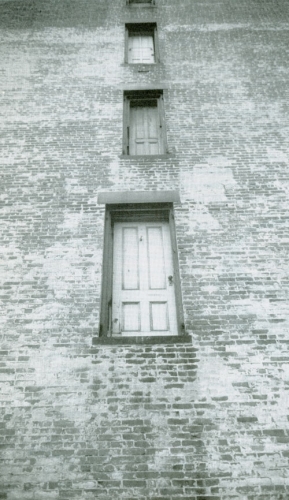

For some time after the terrorist attacks and the start of the war, I also found myself thinking of the Buddha’s admonition to reflect on our own death, and the fact that we can’t know when or how it will happen. “Of all mindfulness meditations,” said the Buddha, “that on death is supreme.” The visual images of the attacks and then the war have become tools of that reflection for me, like tantric paintings or the skeletons in Thai teaching pictures. If we are to live with wisdom, then we must live with the specter of death, which was raised for all of us on September 11 and after.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.