Some experiences take us into a realm we’ve rarely visited except in nightmares. And there I am, dragged through scenes that slip out of their contours to coalesce into an entirely new and terrifying aspect. What began as a routine procedure has morphed into a Grand Guignol horror turn, in which I keep trying to believe in what’s happening without any context or rationale to guide me.

I find myself in this condition for almost a month this autumn. Martha, my partner, has gone in for a double knee replacement. Brave, yes, but nothing we can’t handle. We researched, prepared, set up the requisite equipment, invited friends to visit and help with the recuperation process. She is to come home the day after surgery.

Instead, like a cable car careening off its tracks, we hurtle into unknown territory, terrified passengers holding on for dear life. Martha awakes from anesthesia to intense unexpected pain like electric shocks radiating down her thighs. The picture tilts, predictability slips away, and the task becomes a desperate attempt to control the “shocks” by doctors and nurses who have not a clue what the cause might be.

Addled by Oxycontin, Martha cannot control her reaction to the pain, and I enter this madness with her. Most excruciating for me is the absence of the personality I know and love. Instead, I am confronted with an oddly familiar yet impossible stranger.

Helpless, pumped up with adrenalin, soon exhausted, I respond mechanically to what is required of me, entering into the 4 a.m. entreating phone call, the drug-fueled argument, the sight of my beloved writhing in uncontrollable pain on a hospital bed. The situation goes on for days on end, alternating several good hours with another dreaded crash into unbelievable pain.

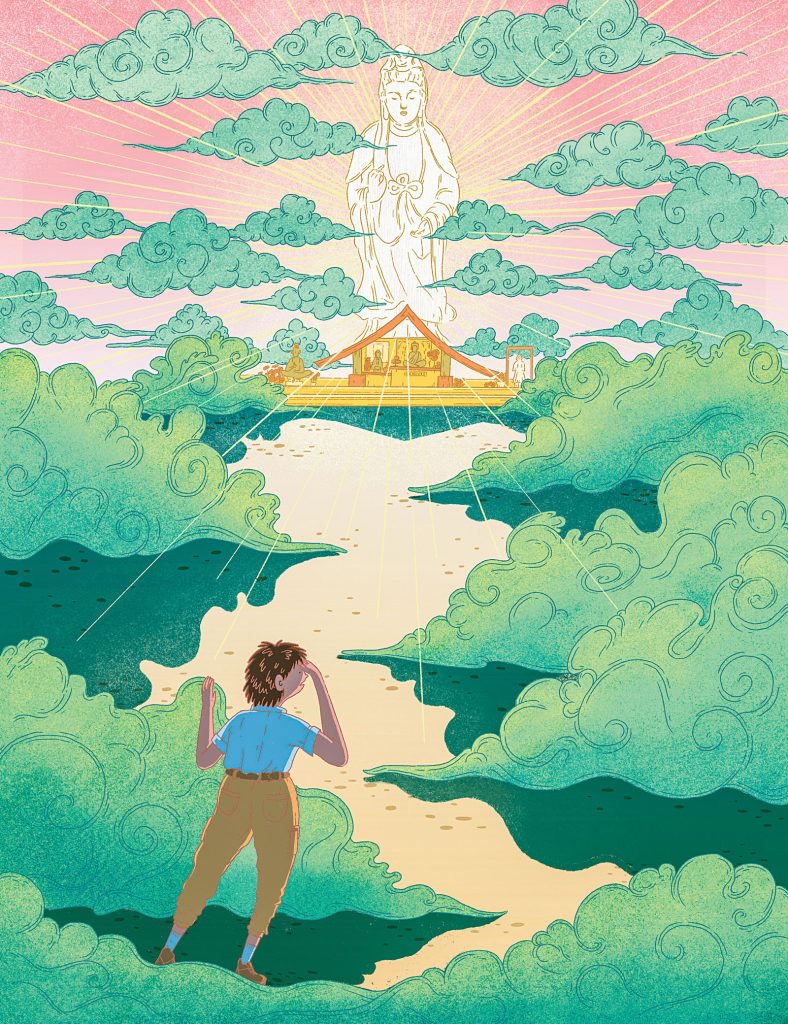

You may ask how my many years of Buddhist practice could be called upon in this emergency. I experience only the necessity to arrive in the moment, help if I can, stand by if I can’t.

And then, despite myself, I am guided to a place of refuge.

The rehabilitation center where Martha lies is situated in a “mixed” neighborhood in Oakland—hilly streets of old frame dwellings in various states of repair or decrepitude, some street trash, some potholes, some well-tended houses. The rehab employees impress upon me their warning that this is not a safe neighborhood to wander around in at night, so some nights I pull out my senior taxi scrip for a ride home. But this night I am driving, and a few blocks from rehab I take a wrong turn.

I know, without a doubt, that I have just been greeted by, held by, blessed by, Kwan Yin herself.

Now I am entering a cul-de-sac of well-maintained houses—when down at the end I see a blaze of light. What could this be? I drive slowly toward it and gradually make out a structure built on the sidewalk, like three little houses, or three show windows open to the street. When I pull up there, I realize this is a shrine. I park, get out to come closer. Behind a protective grate, in each of the three enclosures, stand altars, one featuring a Buddha statue whose neon halo rotates slowly. But my eyes are drawn to the other figures—two large statues of Kwan Yin, the bodhisattva of compassion. Here she is, seated, peaceful, gazing out at the neighborhood—the goddess I have been encountering for 35 years in my Buddhist practice, learning about in my research and writing.

Amid vases of flowers (real ones, not plastic), with music softly playing, the lights offer up this presence from the surrounding darkness. I’m astonished, grateful, and puzzled that I seem to have had no foreknowledge of the existence of this shrine. But not surprised by the figure of Kwan Yin. After all these years chanting to and honoring this bodhisattva, by now I find her as familiar as an old friend, the reality of her interwoven into my psyche.

I breathe in, my tight chest penetrated by the coolness radiating from Buddha’s hint of a smile, Kwan Yin’s lowered eyelids and expression of deep concentration. My experience these days is so very dark and overheated, a sort of fetid scrabbling to stay afloat. But here all is spacious and bathed in light. I feel myself relaxing.

The next day I bring this experience as a gift to Martha. She is pleased, and she takes this expansive feeling with her into the struggle she has now accepted: to wean herself from the opioid that is causing her such disorientation while not actually lessening her thigh pain.

Two afternoons later, when I drive to the shrine, I see that the grating is pushed back. Fresh flowers rest on the three altars, a tray of red apples has been placed at the Buddha’s feet, incense sticks send out their fragrant smoke. Kwan Yin sits, contained and peaceful. And now I see a small woman with Asian features, dressed in black pajamas, sweeping the sidewalk next to the shrine. Noticing my presence, she puts down her broom and comes toward me. She opens her arms, saying, “Oh, I am so glad to see you again,” and reaches up to enfold me in a warm hug; in her embrace, I feel received, and am not at all surprised that she knows the ordeal I am caught in.

Related: A Footprint on the Shore

As I set off for home, despite my long-held secular mindset, despite all the skepticism I normally cultivate about mystical occurrences, religious visitations, divine beings—that stuff is for someone else to experience, not for me—as I drive through Oakland’s streets, I know, without a doubt, that I have just been greeted by, held by, blessed by, Kwan Yin herself, a living embodiment of the bodhisattva. The recognition brings an explosion of light in my chest; I breathe deeply, letting go of the tension in my shoulders.

That night I go to sleep feeling opened, at peace.

The following days bring some solace as Martha finishes her withdrawal from the opioid and begins to practice the rigorous exercises that will allow her to walk well enough to come home. I’m so relieved to see her begin to inhabit the familiar contours of her usual somewhat amused, optimistic self. Although she still experiences the electric shocks in her thighs, she is learning to manage them with the aid of gabapentin, a non-narcotic pharmaceutical that calms the nerves.

In my next visit to the shrine, I notice that the lettering across its front is Vietnamese. The woman, wearing the gray pants and top of a monk, is seated in the center section of the shrine on a small round pillow. She faces the altar, chanting, as she glances down at a book propped before her. I try not to disturb her, but when she notices me she gets up to hug me, and when I ask, she tells me, yes, she is Vietnamese. Now I have a slight ripple of remembrance—didn’t I hear about this shrine years ago, but never was able to find it? Never mind; I am just glad to be in her presence.

Martha’s progress takes us to the final day when she will be released from rehab. But suddenly there is a snag: one of the drugs they give her causes a drop in saline to a dangerous level. She can be discharged only if the saline level has risen to normal. So we await the result of a blood test. It is two days before Thanksgiving. We both desperately want her to be able to come home to our little basement apartment, to come with me across town to the annual holiday doings at our family’s home.

This afternoon, the doctor is scheduled to leave at 5 p.m., not to return until Monday. Anxiously we await the result of the blood test, realizing that if it does not come today we will be stuck in rehab for another agonizing week. The doctor waits with us, sharing our urgency. It is 4 p.m.—nothing. It is 4:15 p.m. I realize that we need help—perhaps we can call upon Kwan Yin? I remember that her shrine is only two blocks away; surely I can walk there in a few minutes. So I take the two-day-old, somewhat wilted bouquet from the side table and ask Martha to write a note. She finds a notepad and scribbles a long message to Kwan Yin while I consult my watch, reaching for patience.

Related: Thirteen Hours

Released into the cold outside air, flowers and note in hand, I walk to the corner and then down the steep sidewalk to the shrine. It is open, music playing, the neon halo shimmering around the Buddha’s head. I stand before the largest of the Kwan Yin statues and look for a place to put the flowers. Yes, there just before her feet. I lay them down, carefully, and slip Martha’s note in among their blossoms. “Please, please,” I whisper, “Get us out of rehab! Let us go home.”

Back up the hill, I enter Martha’s room, where she shakes her head. She is still waiting. It is 4:50 p.m.—ten minutes to the fateful hour when the doctor will leave and we will be stuck here through the long holiday weekend. I refuse to give in to discouragement. The doctor hovers in the hallway. Nothing doing. 4:55 p.m. And then, a miracle, he disappears and returns, coming into the room to wave a piece of paper like a happy flag.

“I have good news for you,” he says.

Home is the familiar couch, and kitchen, Netflix, and bed. As Martha enters, stepping carefully, steadied by the metal frame of a walker, she takes a deep relieved breath and smiles in gratitude. For a week we help her settle and deal with visits from a physical therapist and an occupational therapist. She is determined to be able to walk well on her new knees, and takes each visit by a friend as an opportunity to be accompanied on a walk up the sidewalk. When the occupational therapist suggests that she is now able to stand at the sink to wash dishes, I am discreetly pleased, and notice that a few days later she gives it a try.

But there is something more to be done. Martha has no visual awareness of where she was staying in Oakland, at the rehab center. She has no idea of what it looks like from the outside. And she can only visualize the shrine from my descriptions. Committed as I am to location, to specificity, always wanting to orient myself, I offer her a tour of rehab and the surrounding streets.

So one afternoon she walks slowly up the driveway to the car, and we drive on the freeway, then the city streets, to the neighborhood of old houses—to the block where a low, spread-out rust-colored building squats. We park, and Martha uses her walker to go inside the lobby. The young nurses and aides at the desk look up to grin at her in surprise. “Oh, it’s Martha!” And as she approaches them, “Look at you, walking so well!” She thanks them for their care. We glance into the room where she had slept and struggled, and then in the hall we meet a particular resident, an old Asian woman wearing a scarlet vest embroidered with a dragon’s taut, coiled body and fierce head—one of the people with whom Martha had developed a friendship. They greet each other, clasping hands.

Then we are back in the car, to drive down to the shrine. We park, and I help Martha step off the curb and cross the street. The shrine is open, shining and clean, with fresh flowers before each of the statues, fresh incense sending out delicate ribbons of smoke. Voices chant; bells punctuate the rhythm.

The energy of compassionate caring exists in our world and can be present to us.

Then the woman-of-the-shrine is coming toward us. She opens her arms wide to embrace Martha, holding her for a long time. And welcomes me like the old friend I am. We stay for a while, smiled upon by the Kwan Yin statues, and before we leave, we see our host bustling in the shrine. She emerges to bring us a bag of apples. No, we must take them! she insists. And she carries the bag for Martha as she helps her into the car.

At our homecoming a certain lighthearted energy carries us up the driveway and around the back of the house to our entrance. I bring the bag, wondering what to do with this overabundance of fat red apples.

That evening, after dinner, inspiration dawns. I evoke my straight-backed, redheaded Midwestern mom. She was of Scottish descent: she made good use of everything. I see her in our kitchen at home cutting up apples for her “apple brown Betty.” Thank you, Mom—message received.

Martha enthusiastically agrees to help. She slices the apples while I chop the walnuts and get out the raisins. I mix oatmeal with brown sugar. Then I stir everything together, put it in a baking dish and add some dabs of butter.

A half hour later, Kwan Yin’s gift emerges from the oven, sweet and crunchy.

Looking back at these experiences, I could explain them as a product of the unusual circumstances of Martha’s medical emergency and my own fraught, off-balance state of mind. Yet in retrospect it all feels unremarkable. Of course I would be led to the shrine, given my years of engagement with Kwan Yin. Of course that spirit, that energy would find me. Of course she would be sweeping the sidewalk when I arrived, and would recognize me—so glad you are here again, she said.

So many of my Vipassana sisters and brothers are interested only in meditation practice, recoiling from the devotional dimensions of Buddhist engagement. Yet despite our loyalty to our Western materialistic and scientific view, we may come to suspect that reality is actually multidimensional, that vestiges of other worlds sometimes accompany us, that a sacred embodied presence may be available to us if only we are open to it.This can happen in the meditation hall, in moments of crisis, on the sidewalk of our hometown, anywhere at all. The energy of compassionate caring exists in our world and can be present to us.

Days after our last encounter with Kwan Yin, I went online to find the information I had vaguely remembered. An article had been published four years earlier in the local newspaper, followed by another article in a Buddhist magazine. Here were accounts of how the shrine had been created and developed; stories of the caretaker, a real-life woman with a name and a history. Here were descriptions of how the crime level dropped in the neighborhood after the shrine had been established. All very interesting, but…

I closed the files, finding myself ambivalent about this story of the shrine, not wanting to pursue it further, wanting instead to stay with my own internal reality, part miracle and part ordinary occurrence. I encountered her there at the shrine. I am glad there is a physical place to go back to; I may visit it now and then to bring a flower, or a plea for help. And looking back, I notice that surely in this instance it was the very intensity of the suffering that opened the way to the visitation and made me ready to receive the comfort of her presence.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.