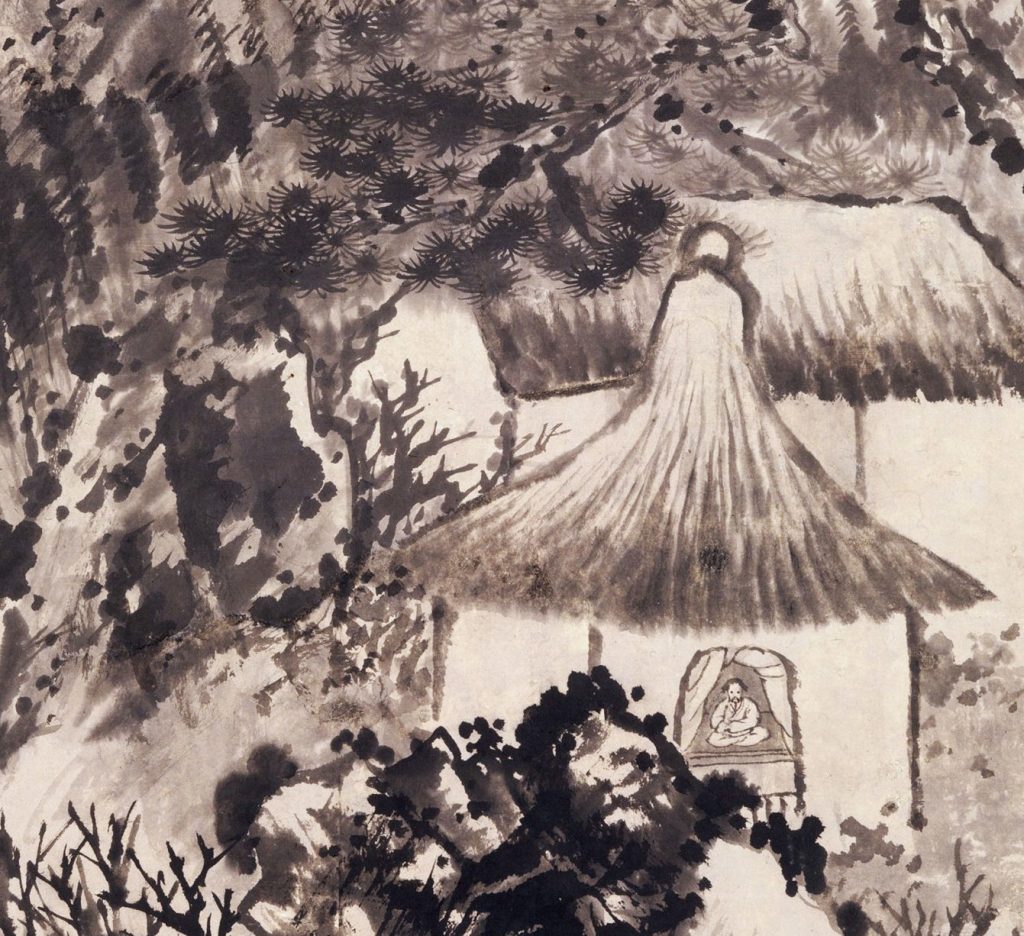

I’ve built a grass hut where there’s nothing of value.

After eating, I relax and enjoy a nap…

Though the hut is small, it includes the entire world.

In ten square feet, an old man illumines forms and their nature.

—Shitou Xiqian (700–790 CE)

When I first heard Shitou Xiqian’s poem “Song of the Grass Roof Hermitage,” I immediately identified with its message. Although I do not live in an 8th-century hut in China but rather a ground-floor flat in rural England in the third millennium CE, my life is limited to a small space similar to Shitou’s. For him, hermitage is out of choice. My own confinement is less voluntary, as it is the result of long-term illness.

In December 1995, I contracted Epstein-Barr virus (widely known as mono in the US and as glandular fever in the UK) while working as a plant biologist in Switzerland. That went on to become the post-viral condition myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), also known as chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). My symptoms have varied over twenty-seven years of illness, but I am currently confined to my flat and limited in my mobility.

A few years after developing ME, I attended a weeklong yoga course specifically designed for those with chronic illness. At the course, one of the instructors suggested that we could view our condition as a choiceless retreat. At first, I found that suggestion almost offensive, as I wanted to be out in the world living my life, not stuck inside the same place for months and years. This way of life felt more like a prison than a retreat. However, as time went on, I began to see the wisdom in the instructor’s words. Although I had little choice in how much time I spent inside four walls, I did have control over how I thought about the situation—and how I chose to spend my time in confinement for however long it was to last. Illness may have limited my ability to do many things, but it has provided more time and space for contemplation and spiritual practice in lieu of being able to work. Moreover, the pain and uncertainty that come with long-term illness provide a strong push to find a way out of suffering, or at least to develop ways of living with it on amicable terms.

In hermitage, as in illness, life grows smaller and quieter. Within this quieter space, small things become more noticeable and greater sources of joy. This is just as true of zazen—as the mind stills, we hear the call of birds or notice a leaf spiraling in the wind or the glow of the sun on powder-puff clouds. In our hut, we see how the view from the window changes daily in tune with the weather and seasons. Growing plants and the phases of the moon chart the passage of time, and putting out seeds and nuts for birds and squirrels offers companionship.

By giving ourselves completely to what is here and now, there is a fullness of experience untainted by comparison.

For many people living with illness, being confined to one space for long periods of time may be the norm. For others, it occurs only during bad periods or flare-ups. In recent times, a large percentage of many populations experienced this kind of confinement during COVID lockdowns. For many of us with chronic health conditions, there was very little change; this is life as we know it, and it continues to be so now that most COVID restrictions are over.

During periods of involuntary confinement, there is little choice but to take on the life of a hermit. We can either embrace this change or fight against it. We may feel very limited in contrast to the expansive life we used to live, but is life measured in terms of how far we travel and how much we do? Can a life be as fully lived in one hundred square feet as it can through regular travel and exploration of new things? I believe so. In fact, the lack of mental novelty can even be conducive to going deeper into life and our own experience. The 13th-century founder of Soto Zen Buddhism, Eihei Dogen (1200–1253), expresses this beautifully in his essay Genjokoan:

A fish swims in the ocean, and no matter how far it swims there is no end to the water. A bird flies in the sky, and no matter how far it flies there is no end to the air. However, the fish and the bird have never left their elements. When their activity is large their field is large. When their need is small their field is small. Thus, each of them totally covers its full range, and each of them totally experiences its realm.

As a former botanist, I would love to have a large and rambling garden to tend and to take long walks through verdant hills and forests, but at present, all I can manage is to tend a dozen or so containers growing medicinal and culinary herbs in front of my flat. Still, the fullness of attention I can give to those dozen pots is without measure, as is the joy it brings.

At a lower level of energy, during one of the times when I was at my sickest, I lived in the guest bedroom at my mother’s house and took strong sedating medication to relieve the pain of muscle spasms. The one thing I could do each day, aside from eating and toileting, was to light some incense and recite a few Buddhist verses. That practice became deeply important for me, even if the vast majority of each twenty-four-hour period was spent supine in bed.

Were I to compare those experiences to what I would have ideally liked to be doing, a lot of the joy in them would be lost. By giving ourselves completely to what is here and now, there is a fullness of experience untainted by comparison. The fullness does not come from the greatness of the experience but from how completely we give ourselves to it. Totally giving ourselves to life, the self falls away, and there is just action and the experience of it.

In writing this, I don’t want to paint a portrait of life as a chronically ill person that does not recognize the cycles of pain, fatigue, and numerous unpleasant and disturbing symptoms that most patients experience. I do not wish to minimize anyone’s suffering or propose that chronic illness is some kind of golden idyll. It really isn’t. I feel privileged to be able to do the things that I can do, and I know that others may not have the capacity to enjoy even those. However, just because our life is confined to a smaller space does not mean that we cannot live fully. During periods when I have to surrender to illness and take to bed, I also try to do that as fully as I am able, even with all of the fears and imagined scenarios that often accompany those times.

Shitou writes of his grass hut, “Though the hut is small, it includes the entire world.” Our illness, too, includes the entire world. The haiku poet Yamaguchi Sodo (1642–1716) expresses it similarly:

my hut in spring

there is nothing in it

there is everything

For those living with chronic illness, perhaps there is wisdom in exploring what we do have rather than thinking about what we have lost. Instead of craving something else, we find intimacy with what is here and now, letting life come to us on its own terms without making demands. It may not be the life we want, but it is the life we have, and it is full and rich with experience. Our grass roof hut may be a room in a small rural house, a flat in a large city, or even a hospital bed. Regardless, we can live in it as fully as we can, drawing on the wisdom and experience of hermits of centuries past who learned to be content with a simple life in a small space.

Shitou concludes the “Song of the Grass Roof Hermitage” with the lines:

Let go of hundreds of years and relax completely.

Open your hands and walk, innocent.

Thousands of words, myriad interpretations,

are only to free you from obstructions.

If you want to know the undying person in the hut,

don’t separate from this skin bag here and now.

The Buddha way does not lie outside of this skin bag—this human body—and practice and realization are not limited by large or small, old or young, sickness or health. Buddha action arises out of sincerity rather than the magnitude of what we do. While we may have limited choice over our bodily capacity for activity, we are free to choose how wholeheartedly we live, and maybe we can look to the hermits of the past for inspiration in doing so.

⧫

Treeleaf Zendo and the Monastery of Open Doors are digital practice places for those who cannot reach a physical zendo for reasons of health, geography, work hours, or a number of other reasons. Treeleaf and the Monastery of Open Doors provide zazen sittings, retreats, discussion, and interaction with a teacher, as well as a pathway to nonresidential Soto Zen Buddhist priest training. Read more about their priest-training program in the article “The Monastery of Open Doors” from our Winter 2022 issue.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.