Buddhism + Self-Help: Table of Contents

Go Bang Your Head Against the Wall, by Noelle Oxenhandler

It’s All for the Better, by Clancy Martin

Saving Vacchagotta, by Mary Talbot

Self-Care for Future Corpses, Sallie Jiko Tisdale

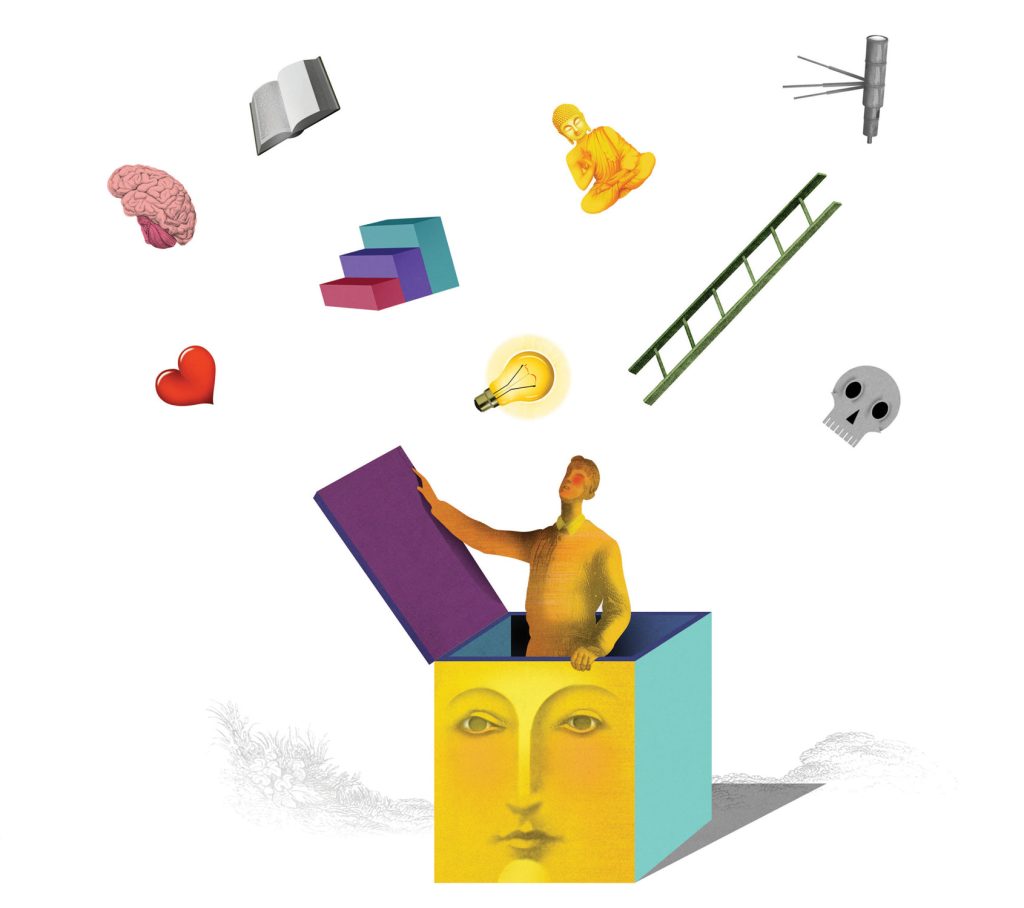

Even if we wouldn’t be caught dead in the self-help section of the bookstore, the truth of the matter is that we’re all self-help disciples. We have a habit of endlessly evaluating everything, from our jobs to our hobbies to our relationships, with one self-serving question in mind: how can I be better?

This issue’s special section explores the interface between self-help and Buddhism. There’s no denying that the former has found in the latter an especially enthusiastic religious partner: once buried in New Age shops, Buddhist books can now be found in the self-help section of any neighborhood or chain bookstore. This state of affairs shouldn’t be particularly surprising, given how involved Buddhists have been in the redefinition and expansion of self-help.

Buddhism’s focus on human ignorance and mental poisons as the causes of discontent would seem, at first, to make it a kind of self-help methodology. In contrast to the Judaic and Christian traditions, for instance, Buddhism does not specifically advocate that its followers pursue social justice or transform social institutions. Instead, it implores its adherents to protect their own minds, to train them with diligence, and to support others on the path.

Yet Buddhism remains distinct from self-help. While much self-help literature limits itself to providing a combination of information and techniques, Buddhism aims to generate insight, particularly into the status of the self, with the aim of ridding us of the selfish desires that often spur our quest for betterment in the first place. Its philosophy, which breaks down the person into its constituent parts, is meant to demonstrate the absence of an unchanging and abiding essence in any of them or in any combination. Though we might feel as though there is a self in control—like the little alien pulling the levers inside the cockpit of a human body (think Men in Black)—this kind of self, according to Buddhist philosophy, doesn’t exist. Buddhism, then, can teach us what the self in self-help is—and isn’t.

If our ostensibly independent self does not exist in the way we thought, if it is not so much a self-possessing agent as a convenient explanation—the product of psychic imprints, inherited habits, and environmental forces—the best self-help might be to question the very fixation on the self as a given, as enduring, and most importantly, as isolated and alone in its predicament. People are, after all, seeking self-help in large numbers, most likely driven by the persistent sense that whatever they do, they’re not enough—as well as the loneliness that feeling engenders. Wouldn’t the best self-help, then, be a kind of solidarity? If Buddhism can help us to see beyond the self, ushering us out of our shared isolation, it might be exactly the help we need.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.