When the wanderer Vacchagotta went to the Blessed One and . . . after an exchange of friendly greetings and courtesies, he sat to one side. As he was sitting there he asked the Blessed One:

“Now then, Venerable Gotama, is there a self?”

When this was said, the Blessed One was silent.

“Then is there no self?”

A second time, the Blessed One was silent.

Then Vacchagotta the wanderer got up from his seat and left.(Samyutta Nikaya 44.10)

Vacchagotta, bless his heart, is the truth-seeking gadfly of the Pali canon, buzzing into the Buddha’s presence at regular intervals, asking the questions that have tormented and goaded wanderers for millennia. What is my self? Is there a self? Is the cosmos eternal?

In refusing to answer Vacchagotta’s questions, the Buddha reveals himself as the self-help guru of them all, in the most literal sense. He is telling us: don’t mess with anything that won’t help you get to release; focus only on what can lead to your ultimate well-being and happiness. The implication of his silence on the issue of whether or not the self exists, which he explains later in the sutta to Ananda and elsewhere in the canon, is a signpost for his entire teaching on anatta, or not-self.

Ananda is flummoxed by the Buddha’s silence. So the Buddha asks, “If I—being asked by Vacchagotta the wanderer if there is a self—were to answer that there is a self, would that be in keeping with the arising of knowledge that all phenomena are not-self?”

“No, lord.”

“And if I—being asked by Vacchagotta the wanderer if there is no self—were to answer that there is no self, the bewildered Vacchagotta would become even more bewildered: ‘Does the self I used to have now not exist?’” In other words, the Buddha cautions, don’t get gummed up in things that aren’t worth identifying with; drop the kinds of thoughts and actions—the clinging—that will only prolong your suffering. We needn’t worry about what the self is—that is a question to be put aside—but work diligently to determine what is not self. The Buddha’s aim was to save Vacchagotta, and the rest of us, from getting caught up in a snarl of distraction, or a “thicket of views,” that effectively barricades the path leading to awakening. If only we all were the quick study that Vacchagotta turned out to be.

Nowhere in the canon, in fact, does the Buddha ever try to define what a person, or a self, is.

Whether there is one, and whether it is the kind that could benefit from Eckhart Tolle’s power of now or Marie Kondo’s life-changing magic of getting rid of household crap (both have merit) isn’t the issue. Puzzling over the metaphysics of the self, the Buddha said, pulls us away from what really matters, and from posing the question about ourselves that really matters: what can I do, right now, that will lead to lasting well-being and happiness? (For Kondo, evidently an animist, it involves the proper folding of your long-suffering socks.)

While the Buddha would not enter into discussions about the existence of the self (and admonished his disciples to avoid them, too), he did instruct his followers to employ the perception of self as part of a strategy for gaining release. Indeed, he offered a trove of instruction for shoring up the healthy sense of self that is required to get on, and stay on, the path. Without it, no release is possible. A verse from the Dhammapada sums the project up neatly:

Your own self is your own mainstay,

for who else could your mainstay be?

With you yourself well-trained

you obtain the mainstay hard to obtain.

Our first duty, then, in order to be that mainstay, is developing the integrity of what we see as the self. It’s like an agent who must keep herself in top form for a mission. It’s the paddle that powers the raft of the teachings. Without both working in tandem, the teachings are of no use. To accomplish that, we need to figure out what is not self and stop trying to own it.

Intrinsic to comprehending not-self is seeing what lies beyond our control. If we have no control over something, the Buddha asked, can it really be part of us? His test case is the five “clinging-aggregates”—the elements we habitually see as comprising who and what we are: form (the body), mental fabrications (thoughts), feelings, perception, and consciousness. We start out with a modicum of control over these, which inspires us to identify with them in the first place. But through the practice, we begin to fathom how illusory that control is, and how unreliable the aggregates are. Recognizing that, we can put them down, thereby dismantling the unskillful sense of self that makes us suffer. Dropping this kind of identification is like putting down an overwhelming and pointless burden, and opens up a space of enormous relief.

Part of the Buddha’s self-help program is encouraging the practice of generosity and virtue, which cultivate the ground for a healthy sense of self. Generosity is an antidote to clinging—as in our clinging to what the canon calls the “eight worldly dhammas”: wealth, loss of wealth, status, loss of status, praise, criticism, pleasure, pain, all come and go as if in a puff of smoke, whether we want them to or not. Building a self out of those is like trying to live in a house of cards. They, too, are beyond our control. Virtue, for its part, makes meditation and its fruits possible—when we act virtuously and stick to the precepts, we’re not causing harm to ourselves or anyone else, and we’re not wracked with distracting self-recrimination on the cushion.

Of course, the integrity of the self that can help move us toward release also develops, in large part, through the deepening of concentration. “In meditation, we begin to see the limitations, the unsatisfactoriness, the changing nature of all sensory experience,” writes Ajaan Sumedho in Mindfulness: The Path to the Deathless. “We begin to realize it is not me or mine, it is anatta, not-self. Anatta is not a Buddhist belief, but an actual realization.”

Through concentration, we gain insight into how we are actually a roiling composite of shifting selves, each with its own agenda. You need only sit down quietly—or try to write an essay—to hear their racket. “I am someone with something to say about not-self,” says one; “I am someone who has no business writing about not-self,” says another. Or “I am a mother who should be making a nice, balanced dinner instead of working past deadline” or “I am the badass who is going to finish this thing and celebrate with a dinner of cookie dough.” And so it goes. It’s in concentration that we begin to shine a light on the selves, on how they pipe up and jockey for control of our perception. It’s how we see which ones are worth our attention—and have our best interests at heart (like the ones that got you to meditate in the first place)—and which ones need to be ignored.

This is the process of “selfing,” what the Buddha also called making a “me” or a “mine”—of identifying with and latching on to things in the service of constructing a self or selves. In its usual, unskillful form, it doesn’t get us closer to release, or even to feeling better, but instead, knocks us further off course. But there is a skillful kind of selfing, as in developing the self that wants to stop being harmful, to stop drinking or lying or being a jerk. There’s a self that wants to meet aging, illness, and death with equanimity, to find lasting happiness, to get off the cycle of death and rebirth.

Facing up to all the selves and all the unpleasant permutations of the aggregates can be a drag, but it won’t kill us. But the alternative will, says Ayya Medhanandi, a Theravadin nun. They can, in fact, try to destroy us, “each time we are driven out of our present moment awareness, prised away from a direct experience of truth by our ‘need’ to get up and go somewhere, do something else, talk to someone, start a project, surf the net, have a cup of tea.” Our scurrilous selves have a thousand sneaky methods for sandbagging right view.

It is in sitting with, and seeing, all our experience in terms of the four noble truths—recognizing the stress or suffering, comprehending its cause (clinging) and following the path of practice to disidentify with the cause. The Buddha “is not interested in having you speculate about what the self is or isn’t; he’s interested instead in having you watch how you define yourself with each action in the present,” Thanissaro Bhikkhu explains in Selves and Not-self: The Buddhist Teaching on Anatta.

“That’s because the line between self and not-self is determined by what you can and cannot control. The more precisely you see that line, the closer you are to finding the true freedom where questions of control or no control no longer matter.” Ultimately, by not identifying with any phenomena whatsoever, we can go all the way beyond suffering and stress, and never look back.

Through the constant refining of the self—of teasing out what is not self and letting it go—we suffer less, get unburdened, feel lighter. We become more adept at discerning when something is within our control, and bears our acting on it, and when it doesn’t. We can see what kind of perception of self is skillful and put that into practice for as long as we need it, thereby cultivating a reliable inner strength that can ferry us to the other shore. To be one’s own mainstay is to be one’s own self help. Teaching us to do that is the Buddha’s ultimate gift.

♦

Read the rest of the Special Section on Buddhism and Self-Help, “Let it All Go”

EXTRA

3 Un-Self-Helpy Buddhist Books of Enormous Help

1. A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, by Shantideva

Written around the midway point between the time of the Buddha and our current era, the Bodhicaryavatara, a masterpiece of late Indian Mahayana Buddhism, is likely to be a far more accessible read for many than the Buddha’s discourses. Help you it will, but the radical challenge the ten-chapter poem levels against self-centeredness is a far cry from self-help. Rather, it’s all about putting others first.

2. Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism, by Chögyam Trungpa

Trungpa’s Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism, adapted from talks given by the Tibetan Buddhist pioneer in 1970 and 1971, warns against the dangers of interpreting spiritual practice as self-help. When we engage in Buddhism in service of the self, or “ego,” we can trick ourselves into thinking we’re genuinely progressing along the path when we’re just “strengthening our egocentricity through spiritual techniques.”

3. Shin Buddhism: Bits of Rubble Turn into Gold, by Taitetsu Unno

With its emphasis on tariki (“other power”) over jiriki (“self power”), Pure Land Buddhism, of which the Japanese Shin or Jodo Shinshu is a subsect, has to be the least self-helpy school of Buddhism in general. With great facility, Taitetsu Unno [1929–2014], the foremost American scholar of Shin Buddhism in America, initiates an audience inclined to equate Buddhism with meditation into a Japanese tradition that undercuts the centrality of individual effort.

–The Eds.

EXTRA

Serving Me by Serving You

by David Brazier

The term self-help, originally found in the works of the Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle, is best known as the title of a book written by a disillusioned parliamentary reformer named Samuel Smiles. A best seller in Victorian England, Self-Help took the view that a person’s fate was entirely in his or her own hands and simply a matter of effort and application. The rich man in his castle and the poor man at his gate were what they were because of the effort they made and the intelligence with which they made it.

It was a reactionary and oppressive idea, placing the blame for the suffering dealt by social injustice on its victims. We all know that manifold forces shape the fate of a person and that from the perspective of the individual many of these, both positive and negative, come fortuitously. It might be comforting to think that by sheer willpower one can shape the world—and one’s lot therein—according to one’s desires, but spiritual maturity includes the recognition that there are many factors in the material and social worlds that are not answerable to personal wishes.

Of course, the poor man at the gate and others of similar status could greatly benefit from asserting their own collective self-interest. But Smiles’s self-help approach sacralized the supreme agency of the individual at the expense of collective agency, one capable of striving for the good of the whole.

When we talk about human agency we usually mean the power of an individual to do things to produce intended consequences. The devil of it, however, is that our foreknowledge of what those consequences are going to be is imperfect at best, and our intentions behind them often remain invisible, even to us.

We should thus aim to become agents in another sense—that of making efforts toward fulfilling an intention that is not individual. Buddhism is about that kind of agency: service to others and doing whatever is necessary on behalf of a greater need. When Shantideva says, “If somebody needs a bridge, I will be a bridge for him,” he is expressing this sense of acting not on one’s own behalf but in the service of others.

When we become agents in this sense, we play a part in a larger scheme that is not properly our own. The agent does not control the big plan, but can choose what or whom to work for. And what better choice than the buddhas themselves, who are made happy by the joy of all beings? One’s agency, after all, is only as good as the intentions of those whom it serves.

♦

David Brazier (Dharmavidya) is a Buddhist teacher, author, and president of the International Zen Therapy Institute. He is also head of the Amida Order, a Pure Land sangha.

EXTRA

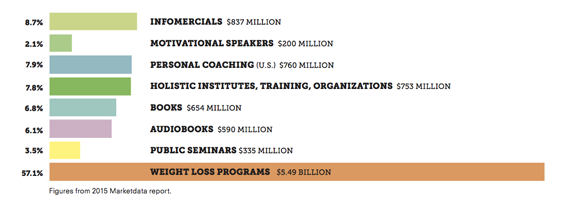

What’s What in the Self-Help Industry?

Value of major market segments (total revenue/percentage of industry) in 2014

EXTRA

Self-Help by the Numbers

Size of self-help industry in 2014: $9.62 billion

Projected size of self-help industry in 2018: $11.62 billion

Percentage of self-help customers who are women: 70

Number of life coaches working worldwide: 12,000

Percentage of global market of life coaching the U.S. accounts for: 50

Percentage of the self-improvement publishing market consisting of diet books: 60

Estimated 2011 income of Dr. Phil: $80 million

of Deepak Chopra: $35 million

♦

Where did we get our numbers? (1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8) Marketdata report, 2015. (4) International Coach Federation survey, 2012.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.