The lovely midafternoon call of an olive-sided fly-catcher serenades my passage through these shadows, as they have for all the years, all the summers that I have been passing through these forests. It’s calling, I know, from some more light-filled place—a break in the canopy, a stream’s edge, a small meadow. The bird’s call keeps me company as I move slowly forward, crawling over giant fallen logs, slipping between spiky branches, inserting myself ever deeper into the heart of the basin. I’m bushwhacking through my home, northwest Montana, less than a mile from Canada. Not a single species has gone extinct in this wild little valley since the retreat of the last Ice Age. This matters hugely to me. I understand the importance of accepting impermanence, but just because I understand it doesn’t mean I’m any good at it. If impermanence matters—if it’s the underpinning of all—then does not permanence matter as well? For each has a relationship with the other.

Here and there, in this dense wet forest, I spy the occasional nicks and stabs of man: clipped saplings, machete- or perhaps chainsaw-swiped 20 or 30 years ago, the vague beginnings of some semblance of a path—though such “trails” always peter out after only a few yards. It is as if the saw-wielding traveler became lost, or exhausted, or otherwise overwhelmed by the voracious embrace of such vegetative presence, and simply quit and turned the saw off and lay down somewhere and listened to the silence fold back in over the brief and clamorous and ultimately useless outburst of the saw. I look about at the dead ends of some of these little slash-patterned slips, half expecting to see the moss-shrouded skeleton of such an ancient quitter.

If there are any, they are already soil: soil, and arnica, and violets. My guess is that these paths to nowhere were faint attempts by the failed drug-runners of the 70s and early 80s, who looked at this spot on the map, thought it could be done, and headed in, much to their eventual regret, and, once they made it out, never returned. The scars of their own schemes and desires are less than whispers, less than evidence now. I may be the only one who has been into this forest since then. How much of the world is built on the backs of ghosts, and does this not make all the more amazing the integrity of the crafted, fitted survivors, the elegant, wilder ones who live here—not effortlessly, by any stretch of the imagination, but with meaning and purpose always?

I’m lost. I always get lost on a good hike. The canopy closes in; I become too attentive for too long to the ground beneath my feet—each next step.

I can’t be too lost; I know there’s a road behind me, and somewhere ahead of me, Canada with its cool promise of escape. And between me and Canada, there is the curious and not very inviting, not very welcoming stripe cut through the forest, 30 feet wide and straight as a laser: a physical attempt to impose psychological order on two nations.

I know the names of the mountains to my left and to my right, so even though I’m lost, I’m bounded. I’m lost, but I know where I am.

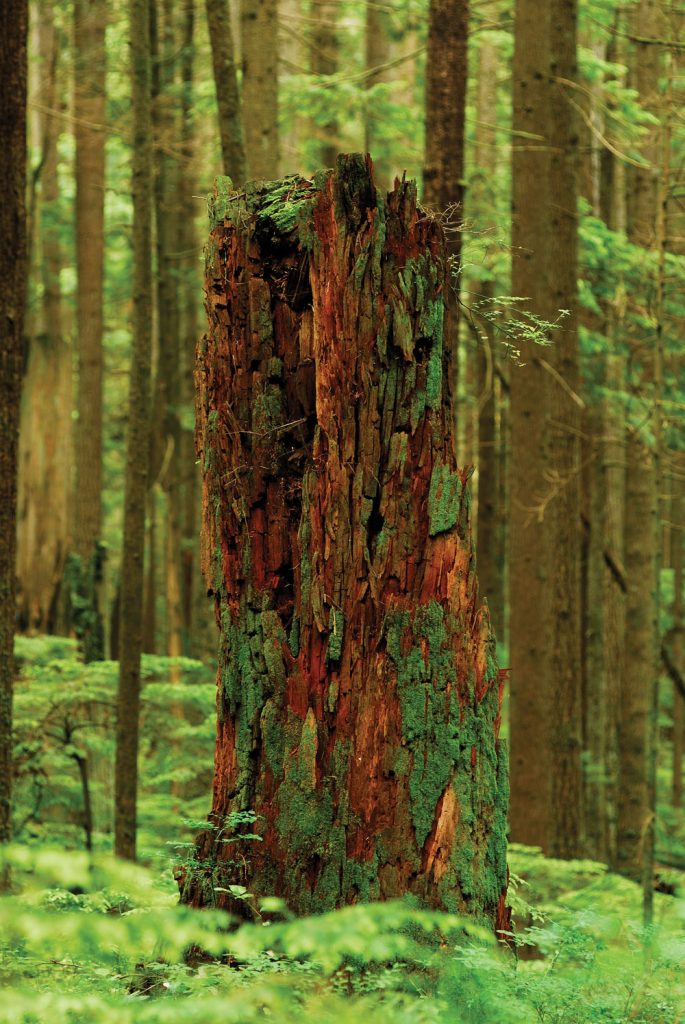

The farther in I bushwhack, the more fallen logs there are, moss-cloaked rotting husks. Sometimes their carcasses lie buried entirely beneath the moss, only to be revealed to me when I step on them, my footprint exploding in a rip of orange mulch, sinking into the mulch up above my heel: centuries of nutrients being reopened, like some fine-baked meal only now being taken from the oven. Out in the real world, or other world, I am a consuming, fire-breathing, world-eating machine, but here in this dark forest I am just one more animal moving through the woods.

There are fallen lodgepole pines, thinner and not yet as decomposed, and in places they form an intricate gridwork, so that it is possible and even easier to travel by walking along these temporary balance beams, a foot or two above the ground, than to always be hopping over them. There is, however, no straight-line passage to be found in following such a route, but instead a riverine cut-and-fill series of switchbacks that eventually becomes mesmerizing, then soothing, to a wanderer who chooses to travel in this manner.

Over time, the angularity of each junction, the obtuse, acute, and right angles, seem somehow to have their edges worn off, so that it feels almost identical to skiing down a steep backcountry slope, or canoeing down a rushing river: the body becomes the journey.

It is in this hypnosis or reverie that I step on one log less anchored or balanced than the others, so that the far end of it tips up like a seesaw. And when the log tips up, it launches into the air, or seems to launch, my fellow and much lighter seesaw partner, which happens to be a pine marten, at least as surprised by my presence as I am by his.

We’re in a little clearing of fallen trees, with only one young green tree still standing, a 40-foot tall alpine fir. Here, startled by my sudden clomping presence on the other end of the same log on which he had been perching, the marten has parlayed my weight at the other end into the mother of all springboard events; he just keeps flying up and up, far over my head. To me, it seems that I have launched him much in the manner of a cannonball. And he continues to soar upward, beneficiary of this odd and random timing, legs windmilling, long tail streaming like a kite tail, before coming to roost in a branch about two feet up. And from there he scampers farther up another ten feet before pausing to peer down at me from a safer vantage.

He’s handsome, looking like a lean little bear, with reddish fur and the splash of blond at his throat, extending all the way up to his bearlike ears, and he’s big for a marten, so much so that at first, as he was flying like a trapeze through the air, I thought he might be a fisher cat.

He stares down at me, catlike, bearlike, and I move a little closer, tightrope walking along that same wobbly log that launched him; as if not liking what he sees, he scoots a little higher up the tree. It is the only vertical tree within leaping distance, so he is besieged, with him above and me below—but he knows I’m going to neither climb that tree nor chop it down, and so he just perches there, looking down, while I balance on the log below and stare up and grin.

I can hear the rush of the creek just beyond, back in the old forest’s shadows, and now that I’ve paused, the mosquitoes find me, are clouding around me, so that I’ve had to brush them away: while up in the marten’s loft, there is a breeze, so that no such insect-swarm plagues him.

I continued to watch him, feeling refreshed and strengthened by him, as if this were but one of a hundred different medicines I could have administered to myself this day, to free my mind of the demons and fevers of the betrayals and cowardice that kept coming back into my mind—the government’s brutal capitulation. And despite the voraciousness of the mosquitoes, I continued to stand there, looking up, grinning, and drinking it in. A single white cumulus cloud drifted slowly past, framing the marten as I watched, and then passed on; and finally, after I don’t know how long, I turned and left, heading down toward the creek, and left the marten alone in the center of his wilderness. Why are we always so noisy, so clumsy, despite even our best intentions? How many millions of years more before we can finally move more carefully?

In the meantime, I know that our clumsiness, like our tendency to wander and become lost, is neither good nor bad—it often defines us—but I didn’t mean to scare the marten, didn’t mean to launch him into the air. I wish it had been otherwise. He’ll be fine, but how graceless of me, and how graceful of him, to fly through the air and grab hold of the tree.

Later in the day, I find the thin stripe of Canada and cross over, a pilgrim, a visitor, unfamiliar in the new land, like all of us, wherever I go.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.