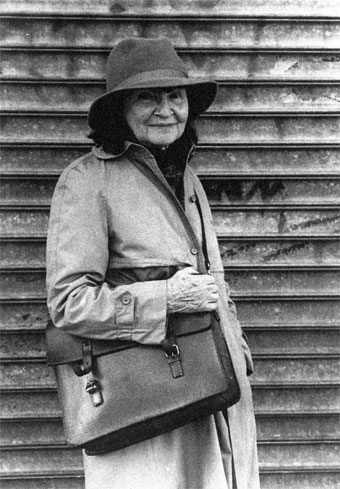

Mary Farkas

(1911-1992)

Mary Farkas, director of the First Zen Institute of America, died on June 7th in New York City. She was eighty-one years old and her long life embodied the transmission of Zen from Japan to the United States. A pioneer of American Zen, Mrs. Farkas’ studies predated the Zen boom sparked by D.T. Suzuki and Allan Watts, and Zen Notes, a newsletter that she published, comprises an invaluable compendium of Zen activity in this country. Her teacher Shigetsu Sasaki, later known as Sokei-an, first arrived in the United States in 1906 and founded The First Zen Institute in 1930. Sokei-an was in the lineage of the great Meiji reformer Kosen (1816-1892), the abbot of the prestigious Rinzai monastery Engaku. In a radical departure from monastic convention, Kosen founded a lay Zen organization in Tokyo called Ryomokyo Kai-the Association for the Abandonment of the Concepts of Objectvity and Subjectivity. This innovative experiment to revitalize Zen in Japan reflected Kosen’s willingness to pay more attention to the spirit of Zen than to the form. Kosen’s search for fertile new ground for Zen was continued by his student Soyen Shaku (1859-1919), who attended the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. It was Soyen Shaku’s students who were most responsible for planting the earliest Zen seeds in this country: Nyogen Senzaki, D.T. Suzuki and Sokei-an’s own teacher, Sokatsu Shaku, whose mission had once been to revive the failing spirits of the original Ryomokyo Kai.

This was the lineage that Mrs. Farkas perpetuated through her affiliation with the First Zen Insitute, through her commitment to disseminating the teachings of Sokei-an, and through her publication of Zen Notes. The Institute, located in Manhattan, has addressed the needs of lay practitioners and has had no formal teacher in residence since Sokei-an’s death in 1945. Farkas herself had no use for titles and only in the last year of her life allowed herself to be called “director” rather than secretary. And yet she has left behind many Zen students at the Insitute and across the country who refer respectfully to her style of teaching from her desk, of teaching by asking questions about one’s life, of teaching by disallowing academic questions about dharma, and, most effectively of all, of teaching Zen by her presence.

Not always certain about how to proceed in the task of introducing Zen to the United States, Rick Fields reports in How the Swans Came to the Lake (Shambhala Publications, 1986) that on a trip to Japan, Mary Farkas asked the Zen abbot, Zuigan Goto-roshi, “Don’t you think we have made some progress in this last half-century?” He replied encouragingly, “Yes, you could say you have taken a step.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.