Mazie Keiko Hirono is a respected US Senator who has advocated fiercely for health care access, immigration reform, racial justice, and gender equality. What is less known is that the Democratic lawmaker from Hawaii was the first Buddhist elected to Congress and is currently the only immigrant in the US Senate.

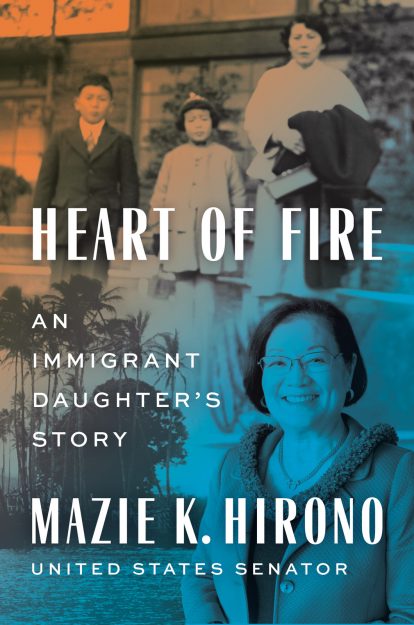

Heart of Fire: An Immigrant Daughter’s Story

By Mazie K. Hirono

Viking Press, April 2021, $28, 416 pp., cloth

Politicians often write memoirs or political manifestos in anticipation of running for a higher office. Sen. Hirono’s new autobiography, Heart of Fire: An Immigrant Daughter’s Story, is not one of those books. It is the story of an Asian American Buddhist immigrant who began her life on the margins and shifted to the center of political power, a journey made possible because of her mother’s “heart of fire.” In my tradition of Japanese Zen Buddhism, it is said that liberation requires great doubt, great faith, and great determination. All three aspects are necessary to actualize a Buddhist life, but first we choose one of them as our gate of entry. Wherever Hirono’s path may take her, this book makes clear that she started upon it through sheer tenacity.

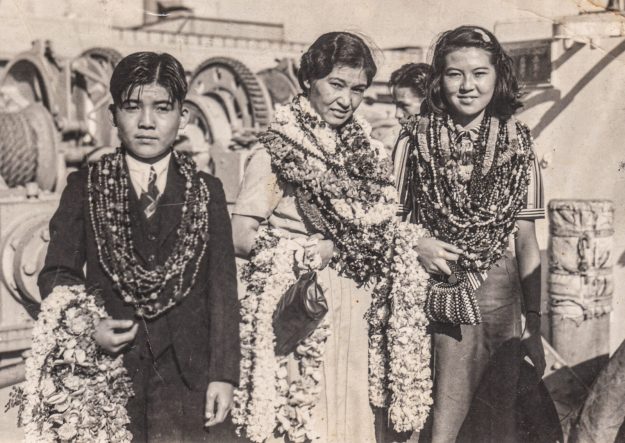

Escaping an abusive husband prone to gambling and drinking bouts, the senator’s mother, Laura Chieko Hirono, immigrated from Japan to Hawaii in 1955 with one of her sons and her 7-year-old daughter, Keiko, who would later adopt the more “American-sounding” name Mazie. Laura had to leave behind her 3-year-old son in Fukushima. She had already lost her other daughter, who died prematurely because of poor access to health care, but managed to sneak the child’s ashes past the immigration officials.

Sen. Hirono’s story sheds new light on the passionate (and soon viral) speech she gave prior to a 2017 vote to repeal the Affordable Care Act: it was motivated not only by her own recent cancer diagnosis but also by her childhood experience of losing a sister because of health care inaccessibility. We learn, too, that Hirono’s outspoken stance against children being separated from their parents at the southern border was informed by her own experience of family separation during immigration.

Wherever Hirono’s path may take her, this book makes it clear that she started upon it through sheer tenacity.

In Hawaii, poverty and humiliation defined Hirono’s initial years in America. Her mother worked, without health benefits, as a typesetter at a Japanese-language newspaper during the day and as a server for a luau-party caterer at night. Although Hawaii has a significant Asian population, Hirono noted that “my ethnic background would not be enough to inoculate a poor immigrant child, especially one who could not yet speak the language, against the feeling of being different.”

As she was learning English and adjusting to elementary school, her grandparents and brother joined the family in a worn-down shack. Her grandmother set up a Buddhist shrine with offerings and chanted Buddhist mantras while moving the prayer beads in her hands. During those days the grandmother was a fervent Soka Gakkai convert; the family had been traditionally affiliated with the Jodo (Pure Land) Buddhist lineage and in time would return to those roots through the Jodo Mission of Hawaii in Honolulu. Young Mazie was impressed by her grandmother’s devotion, but it was her mother’s subdued Buddhism that would influence her more. She writes:

We did identify as Buddhists, though we did not share in Baachan’s [grandmother’s] practice. For us, Buddhism was a way of life. As my mother explained it, our Buddha natures were continuously being revealed in the way we went about our days and in how we chose to treat other people. Mom expressed the cornerstone of our faith with her usual succinctness, “Be kind.”

And so, as is true for many Asian American Buddhists, the practice of dharma for Hirono had multiple registers: formal temple membership, home practice, and embodying a teaching like “Be kind” in daily life. Hirono has always had an organic connection to public service, which was rooted in a Buddhism that treated the entire world—and the alleviation of its suffering—as its temple.

Hirono was naturalized as a US citizen in 1959, the year Hawaii became a state. That event, along with her years of local political activity, eventually led to a congressional run for Hawaii’s Second District in 2007. That year, Rep. Hirono and Rep. Hank Johnson (D-GA) became the first Buddhists to serve in Congress. As she prepared to take her oath of office, controversy arose about how non-Christians should be incorporated into the legislative body. Hirono writes:

Minnesota’s Keith Ellison . . . had caused some consternation among some of our red-state colleagues when he took his oath of office with his hand not on a Bible, but on a Qu’ran…. As a Buddhist, I had used no book at all, a choice that did not escape the notice of the reporters. [I told the press,] “What happened to the separation of church and state and religious tolerance? I believe in those things.”

After being reelected to the House twice, Hirono successfully ran for the Senate in 2020. In her new role, she joined Sen. Sherrod Brown (OH-D) to start a bipartisan “reflections group” to relate “to one another not as politicians but as fellow travelers on a path we all considered to be richly worthwhile.”

Hirono was invited in 2015 to participate in one of the congressional prayer breakfasts, well known for their Christian links. As the designated speaker she had the responsibility of choosing the hymn for the gathering, but as she noted,“ A life-long Buddhist, I knew very few hymns, and so I decided we would sing my favorite anthem, ‘We Shall Overcome.’” For her this hymn was in the tradition of the senbazuru, the practice of folding one thousand origami paper cranes (tsuru), each of which represent a prayer for a better future. She recalled a “chorus of voices from red states and purple states and blue, singing in unison … I can’t help but imagine that the American people might yet make a senbazuru together, a winged chain of hope and healing, a wish for our nation coming true.”

In the more than 150 years of Asian American Buddhism, immigrants and their descendants have had to struggle to find their place in the United States. Today, Sen. Hirono serves as a shining example for any of us interested in actualizing an America composed of a multiplicity of races, ethnicities, and religions. This is the heart of fire she inherited from her mother, and it is what has kept alive the flame of the dharma, the warmth of kindness.

♦

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.