There would seem to be little justification for eating meat. There’s no nutritional need, it’s hard on the earth, not that good for us, and the factory conditions in which we produce “animal products” are so appalling they beggar description.

But not eating meat might be playing things too safe. The function of all our actions as human beings should be to deepen awareness and arouse compassion for the liberation of all beings. But in my own experience, being a strict vegetarian seems to give rise to a subtle buffer between myself and the suffering world, shielding me from the very feelings I would most like to arouse.

Vegetarianism is so “karmically correct” it can isolate us from the experience of other beings, from those mindless ogres who do eat meat, and from the poor meat products themselves. It’s a plea of innocence—”Myself, I don’t eat the stuff…” And I must confess that many of the other “Green” practices—like recycling, Green voting, Green shopping, and money donations—give me the same feeling. You don’t get off that easy.

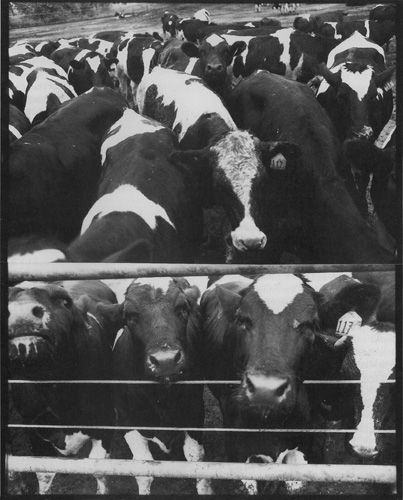

Living in a society based on industrial-strength meat production, we know what is happening to these animals. History holds no greater horrors than those we have created on our factory farms. Each one of us, through our passive and active acceptance of this, has a hand on the cage door, on the knife. Each of us is an accomplice.

But every creature under heaven makes its living this same way, causing harm to others, and leaning on them for food, shelter, and recreation. All day long, creatures are bumping into other creatures, squashing them, killing and eating and drinking them, wearing and using them, walking and lying on them, destroying their homes. There is no personal boundary to this karmic responsibility—it radiates through every jewel in Indra’s net. A karmic debt “owed” by one is owed by all. Vegetarians owe as much as meat eaters, pacifists as much as fighters. There are no personal safe zones, no useful strategies for self-protection.

Therefore, rather than seeking only to avoid causing harm, which is impossible, perhaps we should also be asking ourselves: What can one do with one’s life to offset this “karmic expense,” to repay the debt of harm that inevitably accrues to our personal-universal account?

No one would begrudge the Buddha his private operating expenses, his robe (monocultured crops), bowl (forest products), daily rice (irrigated paddies), or the hecatomb of grasses, flowers, and insects crushed under his many lotus seats. Through his awareness and compassion, he took responsibility for his costs and redeemed them.

We might strive to do the same. We could use our precious and expensive (to others) human life to acknowledge and repay the grandmotherly kindness and the sacrifice of all beings who have willingly or unwillingly surrendered their lives or territory so that we may live.

When one is coming into a first awareness of the frightful suffering of our meat animals, being a vegetarian makes sense. Once this sensitivity is properly established, however, some might wish to resume eating meat—out of compassion—to take further painful responsibility for the suffering of all beings, to arouse broken heart and knowing mind.

Joshu Sasaki Roshi was sitting at the end of a long table all by himself toward the end of his eighty-first birthday party, watching the flies, when he suddenly snatched one out of the air and killed it—just for the sake of practice, for the precision, beauty, and speed of it. This is the way he catches students; it is the practice of a Zen master, and he enjoys it. To a silent inquiry from a surprised student, he replied,

“Die with the fly.”

So, like this, die with your dish of meat, with everybody else’s dishes of meat. Embrace the death of all creatures as though it were your own, as though you were directly responsible for it, which you are. Die a thousand deaths with all sentient beings. Liberate them this way. Get bad broken heart forever for how we are forced to live. Cry whenever you see a well-fed North American.

In the Tibetan and American Indian traditions, meat is a sacrament: eating it is a gesture of sharing in the pain and pleasure of life, a way of taking responsibility for one’s existence, bowing to the law of cause and effect, and an offering of compassion. There is, of course, no difference in principle between meat and vegetables in this regard. Dogen Zenji eats grains of rice with the same fearless mind. Willing to die with everything together.

So how do we turn this nice abstract theory into vivid personal experience, with the sharp edge of real practice? What you’re looking for is a high ratio of awareness to consumption. Killing our food ourselves is of course best, but no one wants to do that anymore.

Try this: Go visit a factory farm or slaughterhouse.

Find other perspectives on food and practice in our special section: Meat: To Eat It or Not.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.