We have been wandering since beginningless time in these

samsaric worlds in which every being, without exception, has had

relations of affection, enmity and indifference with every other

being. Everyone has been everyone else’s father and mother.

–Patrul Rinpoche (1808–1887)

In the ambulance, lurching bumper to bumper down York Avenue toward the emergency room, my 94-year-old mother changed her mind.

“I wanted to die. I’ve been telling everyone.” From the gurney, she craned her neck to look up at me, jouncing beside her in the back of the van. “But here I am strapped to this contraption—” Between blasts of the siren, she wheezed. “All I can think is: I want to live!”

The ER reeked of urine, vomit, and antiseptic. Gurneys lined the corridors, one jammed up against the next; officers from the NYPD lounged by the entrance, chatting up the techs. Call bells and IVs beeped. Doctors and nurses hunched over computers at their stations or rushed back and forth past patients calling from their cubicles. Deluged by addicts who’d overdosed, by car crash and stabbing victims, none of the staff paid attention to my mother, despite her age and her pneumonia.

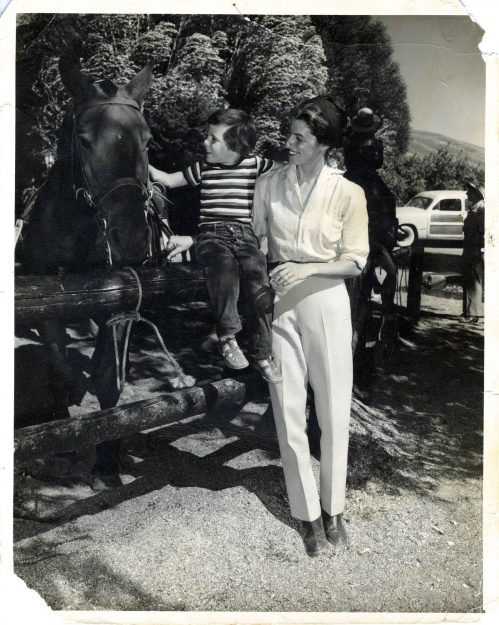

My mother arrived sporting a T-shirt proclaiming in bold aqua: “Nancy at Ninety.” We’d all worn them at her birthday celebration four years earlier. That was her unique hospital attire. Her style had always been her own creation. As a child, she’d insisted on wearing white gloves when she went with her nanny to play in Central Park. Long after she’d stopped riding horses, she wore her old jodhpurs when she chaired meetings at the League of Women Voters or painted in a studio in SoHo. Even in her eighties, she complemented a silk chemise with pants tailored to look exactly like those jodhpurs. In chemise and jodhpurs, she orchestrated her signature dinner parties—small gatherings of eight or nine friends—which she called “my theater.”

My mother wore her T-shirt instead of her green hospital gown throughout her two-day stay in the ER. No matter how I wrangled on her behalf, no beds were available, and neither were any nurses. She voiced her outrage: “Why isn’t anyone attending to me?” She spoke with the entitlement of someone who had been born to wealth and had long since mostly lost it. Her demand for immediate service touched a raw nerve, especially since I was trying very hard to help out. I thought, but didn’t say: No, Mum, you’re not the center of the universe. Just an ordinary human, suffering like the rest of us.

After a half day’s wait, she was given a bed in a curtained space all her own instead of a gurney in the corridor. Although she was squeezed into a shared cubicle that was intended for a single patient, my mother was lucky to have even that. But for her, the cubicle—with its sheet separating her bed from that of a groaning stranger from Bangladesh—felt like an indignity and became the stage set for high drama.

The “villain,” my mom’s cubicle-mate on the other side of the curtain, was an intense little man sporting a dyed carrot-colored Mohawk. With a stream of Bengali invectives, he screamed for morphine as he passed kidney stones. Each time he thrashed in pain, he flung out an arm or leg, bashing into the curtain that served as a makeshift wall separating his half of the cubicle from my mother’s. And with each seeming invasion of her half, she shouted, “Get that crazy man away from my bed!”

The racket in the ER increased as the night went on. All along the corridor, patients, packed end to end on gurneys, pleaded to be housed in cubicles, and those like my mother, assigned to cubicles, begged to be sent upstairs to rooms in the hospital. In the corridor right outside my mother’s cubicle, three hefty NYPD officers closed in on a screaming woman as she jumped off her gurney. Heading toward the street, she pulled on the rubber tube feeding her oxygen and hollered, “Lemme outta here!”

Despite ongoing pleas from me, no nurse or aide took time to replace my mother’s tee with a hospital gown, to wheel her to the bathroom, or at the very least to change her diaper. “I’m utterly wet,” my mom told me. After six hours of asking politely for some help, I wrote a nasty note to the nurse, but then crumpled it up and stomped down the corridor to track down an adult diaper.

I remembered my first clumsy efforts to fasten Caitlin’s diapers. To be struggling with my mother’s 25 years later felt topsy-turvy.

“Mum, I’m doing it,” I tried to reassure her. Gingerly, I pulled back the covers and saw her distended belly, long slim legs. I forced myself to look at her frail pelvis swaddled in the drenched diaper. This is my mother. My tears welled up. Biting my lip, I pulled the covers over her again.

My elegant mum. I imagined her in her cozy living room, surrounded by her vibrant oils painted over many years. She is presiding at one of her dinner parties. With impeccable posture, she tilts her head back in a laugh and crosses one leg over the other to show off a shapely calf. “I can’t stand conversations about ordinary minutiae,” she’d often told me. “At my dinners, I only invite people with something original to say. And I rarely invite people who know each other,” she’d drive home her point, “so there are no boring stories about children and grandchildren.” Like me, I supposed, or my daughter, Caitlin.

Returning to my mother here and now, I pulled back the covers once more. As I tried to roll her on her side, my fingers trembled and slipped. Bumbling, I strained to pull off the sopping diaper, balled it up, and hurled it onto the floor. I strove to turn her, to heave her up without hurting her. But her body resisted my pushes and pulls, and she began to whimper. Stumbling in the cramped space, I finally lifted her buttocks and slid the fresh diaper underneath. I stretched the sticky fasteners all crooked, but somehow they held the diaper on. I remembered my first clumsy efforts to fasten Caitlin’s diapers. To be struggling with my mother’s 25 years later felt topsy-turvy.

As the evening went on, it became increasingly clear that a bed would not free up in the hospital until the next day, if then. “You’re not at the top of the list,” a nurse let us know. “There’s another woman even older than you who’s been waiting 30 hours here in the ER. She has pneumonia too, and she’s a hundred and four.”

I dimmed the lights and, scrunched between two open folding chairs, settled in for the night. Now I followed my breath in and out—not an approach I would suggest to my mother. A third-generation German Jew, my mother was adamantly secular. She worried that Buddhism, which I had practiced for 40 years, might be dangerous, maybe even a cult.

Her IV antibiotics on drip, oxygen clipped to her nostrils, my mother clutched her thin blanket, trying to cover her bare arms. I laid her winter coat over the blanket for added warmth, and she slept. I slept too, on and off, on my two chairs with my own coat as my blanket. It felt a bit like camping out, and I appreciated that—making do as best I could with whatever was available. It’s how I like to live. My mom, absolutely not a camper.

After midnight, the lights suddenly blazed and a handsome young resident strode into our cubicle. Green scrubs, designer haircut, silver cuff on the helix of one ear. He looked like he’d been sent from Central Casting. “How are you doing?” A disarming smile.

“I wouldn’t say I was comfortable,” said my mother, with a raised brow.

The resident dragged a stool right up close to the head of her bed.

Thrilled at the entrance of this new player, my mother struggled to sit up. In her Nancy at Ninety T-shirt, she lengthened her neck and tilted her head back in a characteristic pose, graciously welcoming. “Do make yourself comfortable,” she gestured, with the IV tube swinging. She leaned confidentially toward the young resident. “What is it you would like to discuss?”

Then she turned to me. “Could you roll up my bed so I’m more upright?”

Struggling past the blue IV tubes, the clear line for oxygen, I managed to crank up the bed a few inches.

“My pillow,” said my mother, and the doc reached to adjust that. He stood up, his clipboard in hand, and in a courteous tone rivaling hers began, “There are a few questions I need to ask you.” He cleared his throat. “It’s not that we’re expecting that you won’t be coming out of this hospital soon, but just in case . . . we do need to make sure that you have an advance care directive—”

“Of course,” she broke in, “I’ve set everything up, a health care proxy, all of it. . . . I’ve been fully ready for a long time; it’s really what I’ve wanted. To die, that is. Just think of all the expense and trouble I’m causing everyone.”

“Oh Mum, stop!”

The young doctor continued, “So we’re just going to ask you these questions because it’s part of the required admission process. In fact, we can’t admit you to the hospital proper until . . .”

It’s well past midnight, I thought, paltry chance we’ll be seeing that admission to the realms upstairs any time soon.

“So in the unlikely case that you had a stroke or a heart attack with no hope of recovery . . .” The resident looked down at his checklist. “. . . leaving you unconscious and unable to breathe without the assistance of a machine—”

“Oh, I’ve figured out all that,” my mum cut him off again. Then she directed me: “Dear, do get out my advance care statement from my wallet,” gesturing in the direction of her handbag. Several times over the past few years, my mother had shown me this miniature statement, beautifully calligraphed, then copied and reduced to create a tiny version of itself. “A friend wrote it out,” she told the doctor. That list had been penned by Genie, my college roommate, who had befriended my mother in our sophomore year, when I’d let my mother’s many letters to me stack up unread.

My mother continued, “My young friend copied it in her exquisite hand, beautiful and perfect,” and aside to me, “just the way Genie does everything” (rekindling my old fear that Genie was a much better daughter to my mother than I).

She sure knew how to needle me. “Okay, Mum,” I snapped. I reached for her handbag, rummaged inside, yanked out the wallet, and foraged for the damned statement.

Unflappable, the young resident went on with his protocol. “Well, it’s just that we need to know if something happens, if you have a stroke or heart attack and your condition will not improve, would you allow CPR or an artificial respirator or—”

My mother waved her hand with the IV attached to her wrist. “Oh, I made that absolutely clear. If I would never again be able to enjoy friends, appreciate art, music, or conversation, how could I possibly want to be resuscitated?”

My mum. I had to hand it to her. What spunk she had, what commanding presence.

“Darling, please read the statement to the doctor.”

I adjusted myself so I could get more light from the corridor and read aloud the opening: “If I become terminally ill; if I am in a coma or have little understanding—”

“Barbara dear,” my mother interjected, “tell the doctor about the marvelous film Frontline featured about Genie and Jeff.” She explained to the doctor, “The film’s about Genie’s husband, Jeff, who had some incurable blood cancer. It’s about his death. . . .” As was her way, my mum veered into a new story. “And of course, when Jeff was at Yale Law School, during the weekends when we were in the country, they would stay together at our apartment in New York. That’s where Jeff asked Genie to marry him.” She’d begun with tragedy and moved on to romance.

“Mum!” This time, I was the one to interrupt. “Not now!” Her dramas within dramas drove me mad. I heard my voice trembling. I handed the miniature directive to the doctor.

As he skimmed it, he kept nodding his head. “Yes, well, you do cover the essentials.” An alarm beeped shrilly from somewhere close. “Terrific that you carry it with you, and—”

Abruptly my mum silenced him again. “Tell me,” she interrupted, “Do you have a girlfriend?”

Taken aback at this breach in his doctorly script, the young resident stuttered, “Well . . . well, yes. I do.” He ran a hand through his blond hair. “A nurse on this floor, in fact.” Then he cut himself off, as if he had perhaps said too much.

“Wonderful!” she pronounced. “When all this nonsense is over…” She waved her arm, including in one sweep the corridor of sick and injured, the officers from the NYPD, her nemesis on the other side of the curtain. “You must bring her over to my apartment for a festive party and join me for dinner!”

I’ve heard it said in many dharma talks that every being, in one birth or another, has been one’s mother. Yet I am reflecting about my particular, unique, and challenging mother. On my recent visit, five years after that night in the ER, she is frail, mostly dozing as she enters her one-hundredth year. I happen on a copy of the miniature advance care statement. I sweep back to the dashing doctor, to years of tangles, conflicts, sweetness, fun. Unaccountably, my mind opens—to the fragility of life, the nearness of death. I find myself warmed by memories of my mother’s bold spirit, and the blessing of graciousness, her particular brand.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.