In 1934, an unpublished middle-aged writer named Henry Miller, living in poverty in Paris, had what he termed “an awakening.” He had read occult literature all his life, had just been reading Madame Blavatsky’sIsis Unveiled, but was not given to mystical experience. As he recalled years later,

One day after I had looked at a photograph of [Madame Blavatsky’s] face—she had the face of a pig, almost, but fascinating—I was hypnotized by her eyes and I had a complete vision of her as if she were in the room.

Now I don’t know if that had anything to do with what happened next, but I had a flash, I came to the realization that I was responsible for my whole life, whatever had happened. I used to blame my family, society, my wife . . . and that day I saw so clearly that I had nobody to blame but myself. I put everything on my own shoulders and I felt so relieved: Now I’m free, no one else is responsible. And that was a kind of awakening, in a way.

One suspects that Madame Blavatsky herself, the founder of Theosophy, would have delighted in this story; it has the same mysterious, inexplicable, slightly hokey quality of many of the stories from her own life. What credibility she has in the world today seems largely to rest with the people who were impressed and influenced by her: William James, Abner Doubleday, George Russell (the Irish poet Æ), and W. B. Yeats. Thomas Edison belonged to the Theosophical Society. Albert Einstein reportedly had a copy of the Secret Doctrine on his desk. Christmas Humphreys, founder of the Buddhist Lodge in London, was a devoted follower of Theosophy and an admirer of its founder. And his friend D. T. Suzuki, who was so influential in bringing Buddhism to the West, was once heard to say as he stood in front of Madame Blavatsky’s portrait, “She was one who attained.”

There seems to be little middle ground about Blavatsky. Of the two most recent books that concern her, HPBby Sylvia Cranston (Tarcher/Putnam, 1993) and Madame Blavatsky’s Baboon by Peter Washington (Schocken, 1995), one mentions spiritualist “phenomena”—spoons passing through walls, flowers falling out of the air—as if they were commonplace occurrences, while the other portrays Madame Blavatsky as a laughable charlatan, on a par with P. T. Barnum. Yet, regardless of what doubts may linger about her, it is impossible to deny Blavatsky’s influence on Buddhism, both in Asia and the West.

At a time when traditional Christianity was locked in a debate with Darwin over evolution, when people had to choose between blind faith and the laws of science, Madame Blavatsky proclaimed a spirituality that transcended both, and pointed toward the East. In the East itself, where science and Western colonialism were quickly diminishing the influence of traditional religious philosophies, Madame Blavatsky was at least partly responsible for reviving both Hinduism and Buddhism. In all her writing, with its wild speculations and elaborate mythologies, there is a core of truth that few others were proclaiming at the time. Even the basic tenets of the Theosophical Society, which seem commonplace now, were startling when she formulated them, in the 1870s.

People who regard her as a kind of snake-oil salesman need to confront the fact that Madame Blavatsky never grew rich through her work or particularly tried to, and that her dedication was extraordinary. As a near-invalid at the end of her life, under accusations of fraud from various quarters and having resigned from her officership in the society she had founded, she produced the 1,400-page book that is probably her most famous. There are countless contradictions in her life, but, among the many fervent believers in her work, first among them was Madame Blavatsky herself.

Born Helen Petrovna von Hahn in 1831 in the Russian district of Ukraine, Blavatsky came from an aristocratic family. Her mother was a renowned novelist, her grandmother an artist and scientist. She lost her mother when she was eleven and, as her father was a military officer, her youth was marked by a great deal of dislocation and change. Her formal education was limited, but she was a great reader from an early age and had devoured her grandmother’s extensive library of occult literature by the time she was fifteen.

She was also precocious in other ways. “For Helen, all nature seemed animated with a mysterious life of its own,” recalled her sister. “She heard the voice of every object and form . . . and claimed consciousness and being . . . even for visible but inanimate things such as pebbles, molds, and pieces of decaying phosphorescent timber.” As a child she was friends with a centenarian named Barnig Bouyrak, known as a holy man, healer, and magician. “This little lady is quite different from all of you,” he told her sister. “There are great events lying in wait for her in the future.”

It is not clear why at the age of seventeen this unusual and strong-spirited young woman decided to marry Nikifor Blavatsky, a man she apparently never intended to have much to do with. Sylvia Cranston speculates that she was trying to flee the close supervision accorded young unmarried women in her day. She had planned to flee Russia via the Iranian border following her wedding, but her husband got wind of her plans and intervened. As it was, she lived with Blavatsky for just three months, reportedly denying him his conjugal rights. He finally sent his difficult bride back to her father, but on the way she boarded a small English sailing vessel bound for Constantinople. Her family would not hear from her for eight years.

We don’t know a great deal for certain about Madame Blavatsky until she shows up in New York in 1873. Her detractors claim that she spent her twenties leading an immoral life in the capitals of Europe. (Washington cites rumors of her affairs with a German baron, a Polish prince, and a Hungarian opera singer.) The more official version has it that she traveled in the Middle East, Europe, the United States, and Central and South America.

According to this version, Blavatsky was at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, when for the first time she saw her teacher, who was there with the Indian delegation. She had previously seen him in dreams, but never in the flesh. This was apparently Master Morya, one of two teachers that she would have in her life. (The other was the improbably named Koot Hoomi, and it should be noted that Blavatsky’s critics have doubted that either of these men really existed.) He spoke to her only briefly, saying that he was undertaking some work that he wanted her help with. First, however, she would have to travel to Tibet.

Master Morya and Koot Hoomi were said by Madame Blavatsky to be “Adepts,” guardians of the Secret Doctrine itself. “There is beyond the Himalayas,” she said, “a nucleus of Adepts, of various nationalities. . . . My Master and KH and several others I know personally are there, coming and going, and they are all in communication with Adepts in Egypt and Syria, and even Europe.” It is to these teachers—with whom she communicated telepathically—that Madame Blavatsky ascribed the special knowledge that she acquired throughout her life.

Early in her twenties—still according to the official version—she had tried to enter Tibet from India but was prevented from doing so by the British authorities. Later, she returned to live with her family in Russia, where her psychic powers were much in evidence. “Raps and whisperings, sounds, mysterious and unexplained, were now being constantly heard wherever the newly arrived inmate went,” her sister tells us.

On another occasion, “All the lights in the room were suddenly extinguished, both lamp and wax candles, as though a mighty rush of wind had swept through the whole apartment; and when a match was instantly struck, there was all the heavy furniture, sofas, arm chairs, tables standing upside down, as though turned over noiselessly by some invisible hands.”

She left Russia again. It was during this period of her travels that she reportedly fought on the side of Garibaldi in Italy. “In proof of her story,” Colonel Olcott—her partner in the Theosophical Society—later said, “she showed me where her left arm had been broken in two places by a sabre stroke, and made me feel in her right shoulder a musket bullet, still embedded in the muscle, and another in her leg.”

It is also during this period that she claimed to have done her apprenticeship in Tibet. This was long before Alexandra David-Néel became the first Western woman to enter the Tibetan capital, Lhasa. Blavatsky’s detractors insist that no white woman could have lived in Tibet, but Sylvia Cranston suggests that with her “Mongolian face and olive-yellow skin,” she could have passed. Blavatsky claimed to have studied with a lama, and no lesser authority than D. T. Suzuki has remarked, “Undoubtedly Madame Blavatsky had in some way been initiated into the deeper side of Mahayana teaching.”

In any case, various sources agree that by 1873 Madame Blavatsky was living in New York, perhaps in a large cooperative house, perhaps supporting herself by making artificial flowers. This was during one of the periodic nineteenth-century revivals of spiritualism—communing with the dead and causing spirits to materialize. Among those deeply interested was Henry Steel Olcott, who had risen to the post of colonel in the army during the Civil War and subsequently become a successful New York attorney.

Olcott resolved to investigate these phenomena, particularly at the Eddy farm in Vermont, where many of them were taking place. It was there that he encountered Blavatsky. “My eye was first attracted by a scarlet Garibaldian shirt . . . [She had] a massive Calmuck face, contrasting in its suggestion of power, culture, and imperiousness, as strangely with the commonplace visages about the room as her red garment did . . . Pausing on the door-sill, I whispered . . . ‘Good gracious! look at that specimen, will you?’”

She apparently struck many people the same way. As Rick Fields characterizes her in How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America,

She did not put on spiritual airs. She smoked (tobacco continuously and hashish on occasion) and had a bawdy Rabelaisian wit. She was at once one of the boys (Olcott called her ‘Jack’) and an aristocrat who knew so little about cooking that she once tried to boil an egg by placing it on the bare coals. She was a complex, moody woman given to sudden alternations between flirtatious charm and violent outbursts.

Olcott was to be Madame Blavatsky’s most important partner in her work. They even occupied the same apartment for a time, and wrote at the same table, though no one has linked them romantically. Olcott’s original interest was in spiritualism, but Madame Blavatsky let him know that the occult philosophy behind it was much more important. At a lecture one evening in 1875, Olcott passed her a note: “Would it not be a good thing to form a society for this kind of study?” Madam Blavatsky nodded. Thus was born the Theosophical Society, which formulated (not very grammatically) three goals:

1. To form a nucleus of a universal brotherhood of humanity, without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste, or color.

2. The study of ancient and modern religions, philosophies and sciences, and the demonstration of the importance of such study; and

3. the investigation of the unexplained laws of nature and the psychical powers latent in man.

It was in New York that Madame Blavatsky wrote her first book, 1,200 pages of small print entitled Isis Unveiled, “the most extraordinary book any woman could have written,” according to Henry Miller. She insisted that not only did her teachers virtually write this book for her, they also did the research. “She herself told me that she wrote [the quotations] down as they appeared in her eyes on another plane of objective existence,” Hyram P. Corson, a Cornell University professor, was later to say, that “she clearly saw the page of the book, and the quotation she needed, and simply translated what she saw in English.” Olcott witnessed times when she truly seemed to be taking dictation, when even her handwriting would change. In this manner she composed at the pace of twenty-five pages per day.

The book was a success, but the Theosophical Society—at least in the United States—was not. People seemed interested only in spiritualist phenomena, not in the philosophy behind them, and Madame Blavatsky refused to demonstrate her powers in public, though she showed them rather freely in private. Then, for the first time, one of the Masters appeared to Olcott, telling him “that a great work was to be done for humanity, and I had a right to share in it if I wished,” and leaving behind his turban as proof of his existence. That experience was the chief factor in his deciding to leave with Madame Blavatsky for India.

The Society had a great impact there, where it actually inspired a revival of the ancient traditions. Both Gandhi and Nehru said that the Society helped lead them back to Hinduism. It was also instrumental in reviving Buddhism. “At that period,” the Buddhist scholar Edward Conze tells us, “European civilization, a blend of science and commerce, of Christianity and militarism, seemed immensely strong. . . . A growing number of educated men in India and Sri Lanka felt, as the Japanese did about the same time, that they had no alternative but to adopt the Western system with all that it entails.”

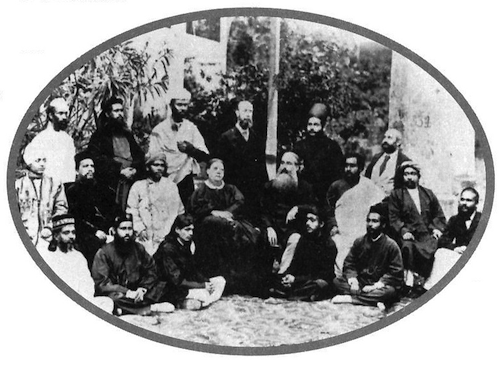

In 1880, in Sri Lanka, Blavatsky and Olcott performed the ceremony of “taking Pansil,” the five lay Buddhist precepts, also taking refuge in Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. “It was the first time the Sinhalese had seen one of the ruling white race treat Buddhism with anything approaching respect,” Rick Fields says, “and it was (as far as we have been able to discover) the first time that Americans had become Buddhists in the formal sense.” Anagarika Dharmapala, the great advocate of the Sri Lankan Buddhist revival, got his start in the Theosophical Society in Ceylon. He became a protégé of Madame Blavatsky’s and remained her loyal supporter for the rest of her life. The occultist Arthur Sinnett, supposedly under the influence of Koot Hoomi, wrote the important text Esoteric Buddhism.

Olcott and Madame Blavatsky founded the journal The Theosophist in 1879, and it became a major outlet for her writing. But in 1884, Blavatsky’s position in the Theosophical Society began to unravel. A housekeeper in Madras, Emma Coulomb, claimed to have staged fraudulent phenomena with Madame Blavatsky—she had “dropped ‘precipitated’ letters onto Theosophical heads from holes in the ceiling,” according to Peter Washington, “while her husband had made sliding panels and hidden entrances into the shrine room to facilitate Blavatsky’s coming and goings and make possible the substitution of all the brooches, dishes, and other objects that were used in her demonstrations.” At first Coulomb attempted to blackmail the leaders of the Society with this information, then went public.

Around the same time, the Theosophical Society was being investigated by the Society for Psychical Research—perhaps not an unbiased source—and Richard Hodgson, the Society’s investigator, subsequently issued a two hundred-page report detailing Madame Blavatsky’s alleged frauds. Hodgson saw Olcott as “a wind-bag full of vanity” and described Madame Blavatsky as “one of the most accomplished, ingenious, and interesting impostors of history.”

Madame Blavatsky wanted to sue for libel, but was dissuaded by Olcott on the grounds that she had vowed never to perform occult phenomena or produce the Masters in public, and therefore couldn’t contradict these charges in a courtroom. Madame Blavatsky resigned as secretary of the Society and returned to Europe. Her relationship with Olcott was effectively over.

Her health had been failing for some time. “This time I have it well and good,” she wrote to a friend, “Bright’s disease of the kidneys.” Peter Washington reports that her obesity was such that she had to be hauled onto the ship leaving India in a chair attached to a rope and pulley. Sylvia Cranston claims that her teachers gave her the choice of whether she wanted to die or go on to write The Secret Doctrine, and she chose to compose what would become her most famous book. The unedited manuscript was reputedly three feet high. The book is founded on three propositions:

1.There is one absolute Reality which antecedes all manifested, conditioned being.

2.The absolute universality of the law of periodicity, of flux and reflux, ebb and flow.

3.The fundamental identity of all Souls with the Universal Over-Soul.

It was this astonishing work—which concerns the “birth and structure of the universes” and “the pilgrimage of man through a series of races”—that was responsible for the conversion of the feminist and Fabian socialist Annie Besant, who would carry the work of the Theosophical Society into the twentieth century. Henry Miller listed it as one of the ten greatest books ever written. Madame Blavatsky published two more books—The Key to Theosophy and The Voice of the Silence—before her death in 1891, which came in bed, in London, after a long period of illness. “In life HPB had a habit of moving one foot when she was thinking intently,” an observer reported, “and she continued that movement almost to the moment she ceased to breathe.”

It is certainly easy to make fun of Madame Blavatsky, and anyone who takes her seriously faces some knotty questions, most of which seem unanswerable more than a century after her death. Nevertheless, one can’t escape the feeling that, however vague she was around the edges, Madame Blavatsky was a remarkable person who saw a deep truth, though she saw it in a complicated way. Alan Watts, who had a talent for putting things in perspective, regarded her as “a masterly creator of metaphysical and occult science fiction. . . . Perhaps she was a charlatan,” he admits, “but she did a beautiful job of it.” Watts’ own mentor, Christmas Humphreys, was rather more enthusiastic:

What a woman! . . . misunderstood, vilified, and abused, and yet with a brilliant, cultured, and deeply learned mind; the very soul of generosity; a woman of direct speech and action, refusing to talk the pious platitudes and nonsense that we chatter under the guise of socially good manners, but offering the truth for anyone who wanted it. . . . In 1920, when I came into the movement, I knew a number of people who had known her well, and on this they were agreed, that after meeting her nothing was quite the same again.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.