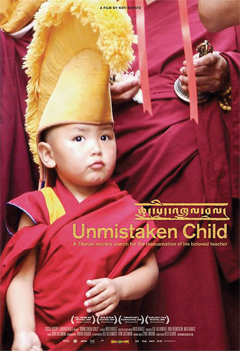

Unmistaken Child

Written and directed by Nati Baratz

Opened June 2009; see oscilloscope.net for theaters

DVD, Oscilloscope Laboratories

102 minutes; $29.99; available October 2009

Toward the end of the new film Unmistaken Child—a chronicle of the search for the reincarnation of the revered Tibetan Buddhist teacher Geshe Lama Konchog, who died in 2001—an SUV slowly makes its way up the winding road to Kopan Monastery in Nepal on the day of enthronement for the new incarnation, a boy not yet four years old. As we watch from inside the vehicle, the boy and the monk who identified him gaze out the window at hundreds of young monks lined up along the road, bowing low and holding out katas—offering scarves—as the car passes. It is a long, affecting scene recording the final step of an arduous quest that stretched over years, and the array of monks seems endless. When the car finally goes through the monastery gates, the line of monks gives way to a crowd of laypeople—mostly Chinese and Caucasian—holding up cameras and jostling for a look at the new master.

It is a striking sight after the first 90 minutes of the film—much of it shot in the sparsely populated Himalayan province of Tsum—and a telling comment on the financial reality of Tibetan Buddhist institutions today, which rely heavily on funding from abroad. Directly and indirectly, the film raises questions about the fate, in the contemporary world, of traditions like this one. Having barely evaded extinction after the Chinese invasion of Tibet, will they find the devotion necessary to sustain them in the now globalized tradition of Tibetan Buddhism?

Tenzin Zopa, the young Nepali monk charged with finding his teacher’s reincarnation, is the psychological focus of Unmistaken Child, and his journey from trepidation to responsibility is rendered in compelling detail. Some of the most sensational elements of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition here become moments of remarkable intimacy. We see Zopa delicately sorting though his teacher’s ashes, collecting the pearl-like relics that are taken as proof of the deceased’s spiritual accomplishment and, with more senior monks, reading signs that point to where Geshe Lama Konchog will be reborn. We see his stunned reaction to being given the assignment of finding the “unmistaken child”—the unquestioned incarnation—for which he feels unqualified. Only buddhas can recognize buddhas, he protests. We follow the earnest young monk as he wanders the countryside, stopping to evaluate every child he meets, gently questioning them and looking for any whiff of proof that this one might be his newly embodied teacher. Most movingly, we watch Zopa as he comes to love Tenzin Ngodrup, the boy he finds, with the same intense devotion he had felt toward Geshe Lama Konchog. Zopa becomes the boy’s principal guardian and tutor, traveling with him to be evaluated by the highest spiritual authorities, playing with him during down times, and comforting him when he is finally taken from his family to live at the monastery in his new role as a tulku—a reincarnate master. While it is Tenzin Ngodrup’s identity shift that is the point of all this effort, it is Tenzin Zopa’s transformation, nurtured by the depth of his devotion, that is at the heart of this film.

Unmistaken Child is director-writer Nati Baratz’s first feature-length documentary, a labor of love that took more than five years to complete [see interview, page 106]. In Zopa, he has found a documentarian’s dream protagonist. Zopa is expressive and vulnerable, by turns joyous and bereft, poetic and humble. That he is engaged in a mystical dharmic quest across majestic Himalayan vistas that culminates in the discovery of an adorably stern and pudgy little boy from a farm straight out of another century makes this an almost irresistible film, whatever your skepticism about reincarnation and the tulku system. Baratz leaves much of the process to the viewer to decipher, employing only a few titles and the occasional reflection from Tenzin Zopa to set the stage and chart his progress. The film has little or no dialogue, and it is not missed: Zopa’s countenance and the landscapes he travels communicate more than enough.

The emotional charge of the film only increases once Zopa achieves his goal and finds the boy. The ritual testing of a tulku candidate will be familiar to viewers who have seen Martin Scorsese’s Kundun, which depicts the 14th Dalai Lama as a boy undergoing the same evaluations. But without the buffer of time, dramatization, and knowledge of the outcome—i.e., the accomplishments of the Dalai Lama—many viewers are likely to find the toddler’s separation from his family unsettling—at best bittersweet, at worst heartbreaking. “Now I have no friends,” the boy wails as his parents leave him at Kopan. They are clearly upset about surrendering their child, but their devotion to Geshe Lama Konchog is undeniable, and there is never much doubt that they will ultimately consent. “If he works for the benefit of sentient beings, then I can give my child up,” the father finally says. “Who could give up their child for nothing?”

Even as we look for something divine in the child, he is still very much a little boy. As he is whisked off to the monastery to live among hundreds of monks without exposure to the outside world, it is difficult not to wonder if this process isn’t ultimately exploitative. At his enthronement, where thousands file by to leave donations and receive his blessing, the child dutifully touches foreheads and doles out katas, but his face only springs to life when one of the worshippers gives him a shiny toy helicopter. Afterward, we see him in his room, surrounded by toys like a child at Christmas, but we can’t help asking if he will still be allowed such simple indulgences as a young master. As artful as Baratz’s spare approach is, by giving his audience so little context for understanding how tulkus are trained, he limits our capacity to make ethical room for what we are witnessing.

The same week Unmistaken Child was released, a British newspaper ran a sensational piece on the 24-year-old Spanish film student identified in infancy as the reincarnation of a popular 20th-century Gelugpa teacher, Lama Yeshe. The article implied that the young man, Osel Hita Torres, had turned his back on his tulku designation, and quoted him as saying, “They took me away from my family and stuck me in a medieval situation in which I suffered a great deal.” Though Torres later denied that he had severed connections with his sangha, the fact that the article ran at all suggests how quick we are to debunk what falls outside Western cultural norms. But is the tulku system indeed an inhumane tradition, ill suited to 21st-century life, or is it justifiable, given the good we know tulkus can do in the world?

The Dalai Lama, exhibit A in any case to be made for the tulku system, appears briefly inUnmistaken Child, ordaining the boy, giving him his new name—Tenzin Phuntsok Rinpoche— and directing him to become a “perfect holder of the teachings.” As we see the two together, we are left to wonder: Can Tibetan Buddhism continue to develop teachers of the caliber of Geshe Lama Konchog and the Dalai Lama without the tulku system? Can the devotion that fuels and transforms people like Tenzin Zopa survive without them? While Unmistaken Child makes no judgments about the tulku system, it is an inspiring and unequivocal argument for the enduring power of such devotion.

Read the interview with the filmmaker, “Making a Mahayana Movie.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.