Free as a Fish

A student asked Philip Kapleau Roshi if Kuan Yin, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, actually existed. “To meet [her] face to face,” answered Kapleau, “all you have to do is perform a selfless deed.”

A workshop participant at Rochester Zen Center arrived early. He assumed the older man he saw about the place was the janitor—only to discover when the workshop began that he was the roshi. When Kapleau heard this, he said it was the highest compliment he could receive.

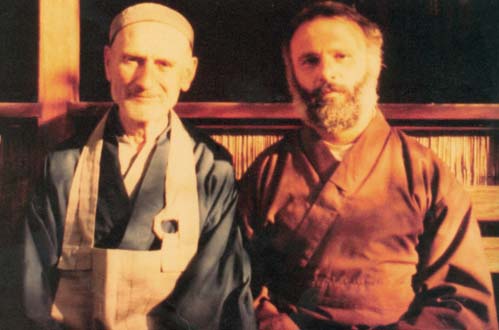

If anyone stands to be remembered as one of the primary Western-born ancestors of American Zen Buddhism, it is Philip Kapleau Roshi, who died on May 6 at age ninety-one, surrounded by students, friends, and family, in the garden of his Rochester Zen Center.

One of a handful of Westerners who traveled to Japan in the years following World War II to experience the rigors of traditional Zen training, Kapleau returned to the States in 1966 to found Rochester Zen Center in upstate New York, the first major Zen center established by an American, and to compile the first text on Zen practice by an American-born Zen teacher. The Three Pillars of Zen, with its mix of fiery lectures by Kapleau’s teacher Hakuun Yasutani, and accounts of contemporary enlightenment experiences and Kapleau’s own training, kindled in American seekers a conviction uniquely suited to their Western upbringing: One did not have to settle for reading about Eastern paths to enlightenment—one could experience it for oneself.

Born in 1912 to a working-class family, Kapleau served as court reporter for the war crimes trials in Germany and Japan, and was deeply troubled by the “appalling suffering” he witnessed in the wake of World War II. Having developed an interest in Buddhism, he visited D. T. Suzuki in Kamakura, Japan, but although he found the scholar’s presence remarkable, his intellectual discourses did not satisfy Kapleau’s growing spiritual hunger.

Kapleau returned to the U.S. in “a mood of black depression.” He became a successful businessman, but felt he had reached a dead end. “My vacuous life no longer had meaning,” wrote Kapleau, “yet there was no other to take its place.” Suffering from ulcers and unable to sleep, he resolved to return to the East for monastic training. He attests in Three Pillars that in 1953, “I gave up my work, disposed of my belongings, and set sail for Japan, determined not to return until I became enlightened.”

Over the next years, Kapleau struggled with pain, fatigue, language barriers, and the intricacies of his own mind—although his depression and ill health cleared up entirely. Finally, in 1958, after intensive study with Yasutani Roshi, he experienced a glimpse into his true nature. The experience, he wrote, left him feeling “free as a fish swimming in an ocean of cool, clear water, after being stuck in a tank of glue.”

Kapleau returned once more to the U.S. in 1966, having received authority to teach from Yasutani Roshi. Kapleau chose the industrial city of Rochester, New York, as the ideal location for a Zen center, saying he hoped the famously inclement weather would push his students inward. Known as the “boot camp” of American Zen, Rochester Zen Center became famous for its intense, disciplined atmosphere and its emphasis on kensho, or enlightenment experience.

My own meeting with Kapleau Roshi took place in Rochester, during research for my chronicle of Western Zen, One Bird, One Stone. Kapleau, then in his late eighties, had retired from teaching. Although he suffered from Parkinson’s disease, he was nevertheless eager to talk. We spent an hour together, his voice a low rasp. By his own admission, Kapleau’s memory and physical energies were not strong, but it was clear that this first American roshi still wanted to share a word of Zen, as long as he had breath to speak it.

Perfect Roses

The late Indian Buddhist teacher Anagarika Munindra used to say that a perfect rose can come from an imperfect giver. Munindra-ji’s words come to mind as I reflect on the life and teaching of my old Zen master, Philip Kapleau. “PK,” as we sometimes called him, could be petty, ill-tempered, and a monumental pain in the ass. He could also be charming, insightful, and an engaging storyteller, guide, and companion on the path. Since his death I’ve received a number of emails from old dharma friends who were at one time or another students of his, and all of them say pretty much the same thing: “My feelings about him may be conflicted, but I owe him a tremendous amount of gratitude.”

I always imagined that I would be present for Kapleau’s death, either by his side, or at least close enough to travel to wherever his body lay, so that I could pay my respects and express my thanks. But as Kapleau often said, “Man proposes, karma disposes,” and as it turned out, on the day of his death I was in the middle of the Atlantic, teaching a course in meditation on a Royal Caribbean cruise liner. It’s unlikely that I would have found myself in this position, however, had I not encountered, many years before, The Three Pillars of Zen, Kapleau’s groundbreaking book on Zen practice. I devoured it twice in succession, and knew without doubt that it outlined the path I needed to follow if my life was to have any meaning. As it was for so many others, Three Pillars was my call to awakening, and the first of the perfect roses Roshi Kapleau bestowed on me.

Here’s another. One time, during a dharma talk, Kapleau said, “Once you truly embark upon the path of Zen, you will lead a consecrated life.” I’ve been working out the implications of this statement ever since. What does it mean to lead a consecrated life? It means that your aspiration to awaken becomes the central organizing principle of your life. It informs your every choice, from the people you associate with, to the work you do to support yourself. It determines what and how much you eat and drink. It dictates your manner of speech, how you walk, how you do the dishes, what you will allow yourself to watch, read, listen to. It even calls into question which pronoun you use to refer to yourself (“I”? “We”? “One”?) Kapleau was a stickler on this point, suggesting that we find ways to avoid self-referencing in speech.

Seven weeks after my brother died, in 1984, I attended the spring sesshin (intensive Zen retreat) at Rochester Zen Center. I was working on the koan “What do you do when a ghost suddenly appears before you?” Roshi explained that in Japan, “ghost” means a despised person—not scary as much as ugly, negative, and difficult. The image that kept coming up for me was that of my mother, whose reaction to my brother’s death was not grief but an uncontrollable rage that led her to lash out at everyone and everything that crossed her path. Dear old Mom became the hungry ghost that inhabited my koan.

I went into the dokusan (private Zen interview) room and instead of demonstrating the answer to the koan, launched into a diatribe about what a bitch my mother had become. Roshi stopped me in mid-rant. “Why don’t you just go home and put your arms around her?” he said. “What else can you do at a time like this?” I had been so caught up in my own reaction to her that it never once occurred to me that this rage was really misplaced grief, and that what she needed was my strength and understanding, and maybe a simple, uncomplicated hug. The next time I saw her, that’s exactly what I gave her, and it was in that moment that my relationship with her began to change. This is what I mean about the perfect roses Kapleau was handing out in those days.

One summer Kapleau came to stay at the Denver Zen Center. This was in the early days of my practice, and I was struggling. Toward the end of a sitting one evening, Roshi told us, “When you ask people what kind of experience they are having with the practice, you usually get two very different kinds of answers. The first group says, ‘Fantastic. The practice is transforming my life.’ The second group says, ‘Oh, I don’t know. I’ve been sitting for a year now and I don’t notice much change. Of course, my wife says I don’t fly off the handle as much as I used to. But I really don’t see it.’ You have to take what the first group says with a grain of salt,” Roshi said. “It’s the second group for whom the changes have really gone deep, so deep that they may not even be aware of them. That’s the real Zen.” It was this sort of off-the-cuff observation that began to shape my understanding of what meditation is, or is supposed to be. “You can let go,” he seemed to be saying. “You can surrender to the practice and trust that it will take you exactly where you need to go.”

An imperfect giver? Maybe so. But Philip Kapleau gave the world a bouquet of perfect roses, and the time has come to thank him for it.

Parting Words

I spoke to Roshi an hour before he died;

friends held the phone to his ear.

He couldn’t reply.

It didn’t matter.

Can a life be apprehended

in a phrase or a verse?

Of course not.

Zen invites us to do it anyway.

“Where there are no buddhas, make buddhas.”

That would suit a transmitter of Dharma,

but it sounds puffed up.

Where are there no buddhas?

The Three Pillars of Zen

made an ancient tradition

suddenly accessible—

“The three-legged frog swallows the giant turtle.”

It is not too late to call to him, wherever he may be:

“Leap right over the barrier of life and death!

Gallop straight through the forest of thorns.'”

Zen sayings gain dignity in classical Japanese.

Choten ya-ya kiyoki koto kagami no gotoshi

banri kumo naku kogetsu madoka nari

Every night the vast sky is as clear as a mirror—

not a cloud for ten thousand miles,

the lone moon round.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.