I don’t know why I took that phrase “wild fox slobber” from Hakuin Zenji, who got it himself from Zhongfeng Mingpen. Maybe it’s because I suspect the old Rinzai master Hakuin, quite a fox himself, was referring to poetry. Backhand acclaim is the way of Zen, a tradition that may have originated in India with the practice of ninda stuti, praise in the form of abusive reproach. The other day I started to read David Schneider’s good biography of the Beat poet and Zen roshi Philip Whalen, Crowded by Beauty. Much of the early part of the book covers territory written about many times, the adventures of the San Francisco poets of the 1950s. Hearing it told again would have made Whalen impatient and grouchy. He might have called it fox slobber.

Schneider recognizes this. He has to inventively retell how the poets Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac, Michael McClure, and Whalen met. How in 1955 they took part in an iconic event, the Six Gallery reading in San Francisco, which was a kind of shot heard round the world for the Beat Generation. The account of the Six Gallery, though I’ve read it told a dozen different ways including Kerouac’s version in The Dharma Bums, does make me miss the cagey Zen poet Whalen, who was regularly self-deprecating, indifferent to fame, but a secret hero of American letters. Kerouac portrayed him as a bodhisattva figure. In 1987, toward the final decade of his life, Whalen received the title Roshi, then served briefly as abbot of the Hartford Street Zen Center.

I remember that shortly after the Six Gallery reading and the national press’s coverage of the San Francisco “scene,” the East Coast poets headed back to New York. Gary Snyder went to Japan for a decade; when he returned to North America he settled in the Sierra Nevada foothills. Of that generation of poets—those who helped make the teachings and mythologies of Buddhist Asia feel hip, naturalized, like they belong here—it was Philip Whalen who stayed on. He lived in the city with only a few hiatuses, part of the San Francisco milieu his entire life. Along with Kenneth Rexroth, McClure, and Diane di Prima, he helped turn the city into a geographic center for Buddhism and poetry. Yet few educated readers know his name, and most academics who look at it think his poetry—as Whalen called it in his poem “Small Tantric Sermon”— “Impossible gibberish no one / Can understand.” Schneider quotes from this poem near the outset of the biography. I had to look it up. Here’s how it ends:

Impossible gibberish no one

Can understand, let alone believe;

Still, I try, insist I can

Say it and persuade you

That the knowledge is there that the

revelation

Is yours.

You could pick similar thoughts, spoken in quite different tones, from a dozen books of Zen or Taoist wisdom. Except Whalen says it with no trace of piety, in that effortless colloquial tone that made his poet friends think him the best of them all. In his iconic poem “Sourdough Mountain Lookout,” he riffs on the Heart Sutra mantra, getting a little closer to its spirit than any straightforward translation:

Gone

Gone

REALLY gone

Into the cool

O MAMA!

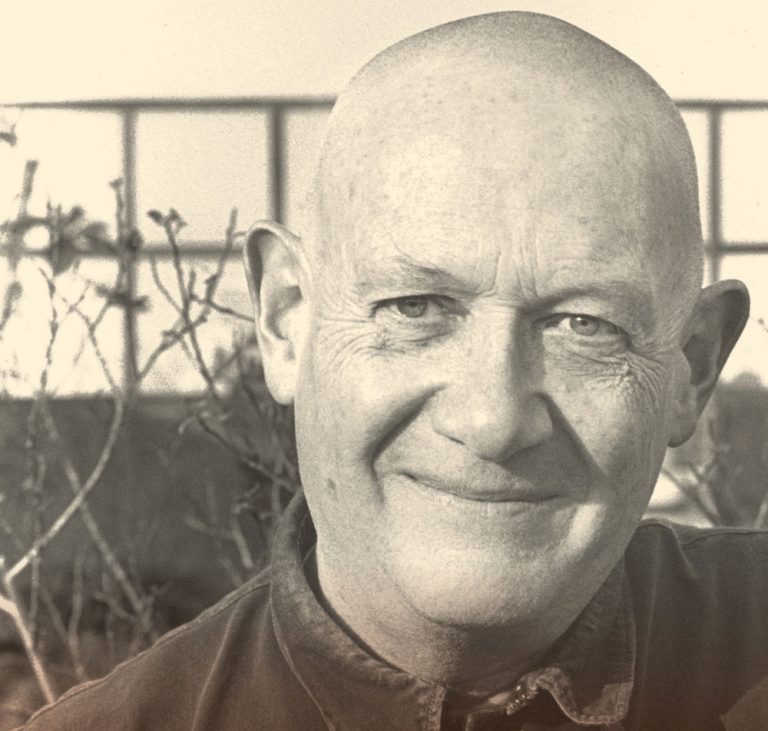

The more I look at Whalen’s poetry the more I see how it echoes the classics, both East and West, from Flaubert to Huineng. It pays tribute, burns a stick of incense at what he’s learned, then with mischief tips the old-timers over. His erudition was notable, from childhood forward. “I dress and talk like a college professor,” he once told Schneider. “They don’t like it.” This is not factually true, especially after 1973, when he went through ordination, had his head shaved, and began to wear robes. A 1968 photo that appears in Crowded by Beauty shows him resting against a rock near the summit of Mount Tamalpais; he wears a large mala around his neck and carries a Shinto ring-topped staff. A conch shell sits next to him and a Sierra cup hangs from his waist. He does not look exactly like a Tibetan siddha or a Zen hermit; but a college professor he ain’t.

Whalen’s vast reading, along with musical instruments and the religious gadgets he acquired during two study sessions in Japan, neither impressed nor chagrined him. They were what he required for sustenance. He also required long stretches of solitude to study, write, play the piano, and sit zazen. He lived for years on the couches or in the spare bedrooms of friends—The Kindness of Strangers he titled one poetry volume—and never held down a job for long. Whalen was enormously reliant on friendship, yet he never lived with a domestic partner. Instead, out of solitude, he could echo—and with the same gesture, parody—the grand masters: poets, philosophers, bodhisattvas, friends, teachers.

You inhabit public buildings?

A taste for marble in a wooden age

A weakness for the epic that betrays

A twiddly mind.

In the high, almost priestly seriousness of the San Francisco poetry renaissance, only Whalen could have used the word twiddly. His goofiness drove some of the poets nuts.

The stanzas I’ve cited so far are taken neither from one of Whalen’s books nor from Schneider’s biography but from a historic 1957 issue of Evergreen Review, “San Francisco Scene.” The issue contains Ginsberg’s “Howl,” Kerouac’s “October in the Railroad Earth,” Henry Miller, Gary Snyder, and Kenneth Rexroth. Whalen’s bio-note for the magazine self-effacingly says, “After war service in the Army Air Force, he attended Reed College and worked for the U.S. Forest Service.”

Philip Glenn Whalen was born in Portland, Oregon, in 1923. His parents raised him in a town called The Dalles, where the Columbia River narrows through a tight rocky chute. He devoured books, spent time outdoors, avoided sports. Norman Rockwell could have painted his boyhood. Even when Whalen joined the Army, he spent all the time he could reading, imagining he would write a huge novel like Thomas Wolfe. He stepped into the annals of North American poetry and Buddhist lore when in 1946 he arrived at Reed College on the G.I. Bill. Two notable students entered at the same time: Lew Welch and Gary Snyder. Snyder recalls that Whalen was the first practicing poet he’d met.

The three young men met William Carlos Williams when the older poet visited Reed. They investigated the Modernist works of Pound and Gertrude Stein, devoured Chinese poetry in translation, found the Upanishads, and then, like discovering a lode of hidden ore, happened on books by D. T. Suzuki. Each of the three in his own way became a resolute adherent of Zen. They each developed a Western calligraphy style, one of the formal trainings available at Reed. Whalen became lifelong friends with Lloyd Reynolds, the professor who taught classical Western pen techniques (as well as William Blake’s poetry).

If all this sounds mythic, it is. Schneider cautions at the outset that one of the models for his book is namthar, the Tibetan form of spiritual biography. “It is not uncommon,” he says of those books, “to read the same story told on three levels: outer, inner, and secret. These levels move from observable facts of daily life to progressively more sublime visions, realizations, and teachings, many invisible.” He does his best to lift a few of these visions and realizations up for the reader.

But as Schneider points out, many of the events in Whalen’s life cannot be seen as observable fact. Compared to friends like the restless, constantly traveling Kerouac, or the disciplined adventurer Snyder, details about Whalen look meager. Few love affairs; not much travel; no crowds vaulting fences to hear his poetry. I do remember a Grateful Dead record with a photo of a crowd on Haight Street: a lonely marquee overhead holds the name Philip Whalen. It could be announcing a little-known Irish welterweight.

Whalen wrote a poem entitled “Ghosts” at Tassajara—San Francisco Zen Center’s retreat, back of Big Sur, in a dusty little gully of the remote Los Padres National Forest. He dated it 14:vii:79 (Whalen dated all his poems). It comes out of a vision. Most people experience such things. Few regard them as visions. Fewer still make them poems.

Of people dead fifty years and not only

people—

Theaters and streetcars and large

hotels follow me

Into this dusty little gully. None of

them ever liked California

Why don’t they stay in Portland where

they belong

I’m tired of themA new ghost in this morning’s dream,

Beautiful and young and still alive

How far will that one follow me? I’m

not chasing any,

Any more.

I wrote an East Coast friend, a longtime reader of Whalen, about Schneider’s biography. I said that it gave little insight into the poetry, but that I had learned many things about Zen. My comrade wrote back to say that was OK. The poems do not ask to be explained, analyzed, critiqued, or read biographically. Zen, on the other hand, has a great many facets worth writing about. And Whalen did live through some of its largest North American moments, from the arrival of Suzuki Roshi in San Francisco to the great rupture at the Zen center he had founded. (I’ll say a word about that below.) Whalen also experienced the range of Zen emotions: interest, skepticism, devotion, boredom, exhilaration, confidence, doubt, despair. He filled his journal with candid accounts, and wrote splendid letters to friends full of elegant calligraphy.

It is almost impossible now to remember how much letters meant during Whalen’s era—one of the great epistolary periods—when a card from a friend seemed like a visitation, and the most articulate, intimate thoughts got committed to paper and sent through the mail. Schneider had access to Whalen’s papers, most of them held by the University of California, in Berkeley or Davis libraries. He quotes from these continually, which gives the book at times the feel of an autobiography or confession—so much so that that by page 100 you can’t help but think of this stormy-tempered, oddly erudite poet as Philip, to sympathize with his tantrums, his insecurities, his fits of temper, and his funny, insightful poems. This tribute to old Chinese master calligraphers is possibly his best known:

HYMNUS AD PATREM SINENSIS

I praise those ancient Chinamen

Who left me a few words,

Usually a pointless joke or a silly

question

A line of poetry drunkenly scrawled

on the margin of a quick

splashed picture—bug, leaf,

caricature of Teacher

on paper held together now by little

more than ink

& their own strength brushed

momentarily over itTheir world and several others since

Gone to hell in a handbasket, they

knew it—

Cheered as it whizzed by—

& conked out among the busted

spring rain cherryblossom

winejars

Happy to have saved us all.

Schneider has organized his book inventively. The first half chronicles Whalen’s friendships. Five friendships each get their own chapter. All the friends are notable poets: Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Gary Snyder, Joanne Kyger, and Michael McClure. Schneider was able to interview the last three, along with numerous poets and Zen practitioners of a younger generation. Poignant, often comical stories and insights pepper the book.

The second half of the volume is a more standard chronological account of Whalen’s life. It too revolves around friendships and tantrums: with Lloyd Reynolds, with Don Allen (his publisher), with scholars, poets, and people in the Zen orders. Most important, it portrays Whalen’s relationship with his Buddhist teacher Richard Baker Roshi.

Schneider’s knowledge of Zen Center doings—his own long involvement with the San Francisco Center in general and Baker Roshi in particular—makes his book carefully informed. At times you feel him moving with quiet delicacy. Talking about the schism at Zen Center, which took place in the eighties, must still not be easy for many of those who felt involved. Baker Roshi had developed the Center faster than many would have liked, with a farm, restaurant, bakery, and poetry readings. He was also regularly absent, raising money or hanging out with counterculture sorts. When it came to light that he had had at least one liaison with a student, the Center’s board voted to remove him as abbot. The fact that all residents were in intensive relationships with Baker—he was the resident teacher—made the board’s action feel to some like a betrayal, to others an overdue intervention. Most felt intolerably conflicted.

Schneider provides the necessary skeletal background without taking on the still-raw wounds—except as events affected Whalen, who ended up leaving for Santa Fe, part of a tiny contingent that remained thoroughly loyal to Baker. In Santa Fe this little group settled into a house, with Baker again absent much of the time. Whalen’s unease with how his training was proceeding made the Santa Fe years painful. Was this part of Baker’s teaching method?

Then in 1987, at the Santa Fe zendo—though the proceedings kept getting delayed—Whalen finally received transmission from Baker. With transmission came the title Roshi. “When the title ‘Roshi’ is given,” Baker wrote, “it means this realization has matured and flowered in practice.” The event, Schneider says, is “an ultimately inexplicable meeting of minds.”

It’s that inexplicable meeting of minds that lends to Zen those thousands of phrases that get under your skin. Is it all wild fox slobber? How can Dogen insist that mountains walk? Why does Hakuin title a book Poison Blossoms from a Thicket of Thorn? What about Whalen, at a Buddhism and poetry gathering at Green Gulch in 1987, saying, “I’m quite willing to talk to people and explain things to people if they have a question or a problem. Or sit doltishly looking out a window. So you’re going to have to, if you want something from me, try to get it. Because I’m not about to offer anything. I don’t have anything to offer. I’m sorry. That’s the emptiness part.”

Much of Whalen’s life looks odd or inexplicable. As he wrote, “The really secret books are dictated to me by my own ears and I write down what they say.” That is why we are so lucky to have his poetry, the writing of his own ears. And to have this biography, which points to the secret books. A poem entitled “Something Nice about Myself” could be Whalen’s own autobiography:

Lots of people who no longer love each

other

Keep on loving me

& II make myself rarely available.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.