The Five Hindrances are negative mental states that impede our practice and lead us toward unwholesome action. All of us have no doubt experienced how sensual desire, anger, sloth, restlessness, and doubt can overtake our minds—not to mention our meditation practice. These negative mind states have enormous potency, and it is difficult to pry ourselves loose from their grasp. In fact, sometimes we take perverse pleasure in indulging them, which of course makes them doubly difficult to overcome. We nurture desire for an inappropriate person; we brood over an argument with a friend; we content ourselves with an outmoded routine or relationship; we obsessively second-guess even the smallest of decisions; we allow ourselves to be consumed with doubts rather than resolving them.

One of the goals of meditation practice is to realize how we support the hindrances and, through this insight, to dismantle them. In this special practice section, five teachers answer questions about some of the most common ways the Five Hindrances manifest in our everyday lives. Through honest examination, skillful action, and compassion we can transform these hindrances into newfound equanimity.

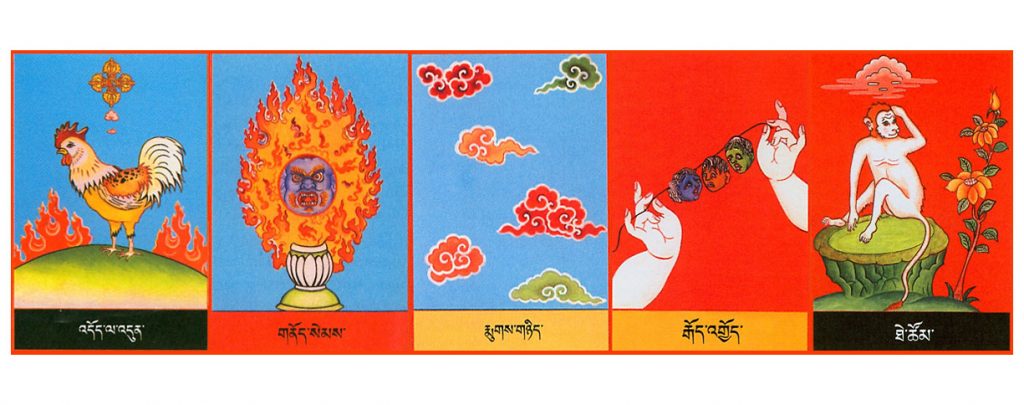

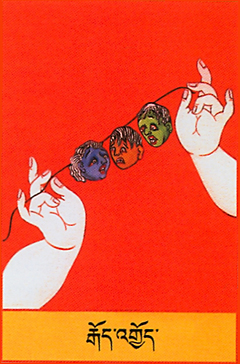

The First Hindrance: Sensual Desire: Q & A with Geri Larkin

I always desire what I don’t have: friends, food, lovers, material possessions. It seems like I never have what I want at any moment, that I’m always thinking, “What if…?” How can I learn to satisfy this desire with what I do have?

My experience has always been that it’s an enormous relief just to admit to myself that I’m obsessed by a desire for something. First, I can stop trying so hard to pretend that I don’t want something that, in fact, I do want. Second, most of the time something I think of as an overriding desire is often more a moment of “wishful thinking.” Often seeing our desire simply as what it is – a desire – allows it to drop away, or at least loosens our hold on it.

The few times when that hasn’t worked, though, gratitude or metta practice has made me sane again. Instead of getting caught up in the desire, I literally start to list all of the things I’m grateful for, starting with the fact that every time I breathe out, my body breathes back in. I suddenly notice all the different colors in my teacup, the sound of the chickens outside. I call a friend, pull out an old journal to remember a former boyfriend. Then I sometimes try a lovingkindness meditation, or chanting, for everyone else caught in the bittersweet cycles of desire.

I am in a committed romantic relationship, but I still feel desire for other people. How should I handle these feelings?

Four kinds of misfortune come

to those who commit adultery:

bad karma,

disturbed sleep, and

a bad reputation

are already known.

There is also the risk

of being reborn in hell.—The Still Point Dhammapada

Desire happens; it doesn’t make you a bad person. People are attractive. They flirt. We fantasize. There is no doubt more than one soul mate for each of us. On the other hand, a solid relationship where two people can take refuge in each other as great spiritual friends, helpmates, and lovers is well worth defending. But how, in the face of desire for someone else?

A powerful antidote is focusing our attention on devotion to our mate. During the Buddha’s lifetime, one of his best friends was King Pasenadi, whose wife, Mallika, was completely devoted to him. When Pasenadi was thrown into jail, Mallika covered her body with honey to provide him with sustenance. Cherishing our mate is a warrior’s weapon against falling into a relationship with the wrong person (yes, that is anyone who is not our mate). It reminds us how much we love this person who shares our bed and how important she or he is to us. Our devotion might take the form of cooking fresh vegetables for dinner instead of microwave stir-fry. Or putting fresh sheets on our bed. Or going for an evening walk together. Taken singly, these actions are little things; writ large, they are a love poem.

If that doesn’t work, Buddha reminded the nuns and monks studying with him that everyone gets sick, ages, and dies. In one case, Buddha made this point by conjuring up a vision of a beautiful woman and making the vision visibly age right in front of a group of her admirers. They got his point: Everything is impermanent, even beauty. Even desire.

Geri Larkin is the founder and guiding teacher of Still Point, the first Zen Buddhist temple in Detroit. She is the author of Love Dharma: Relationship Wisdom From Enlightened Buddhist Women.

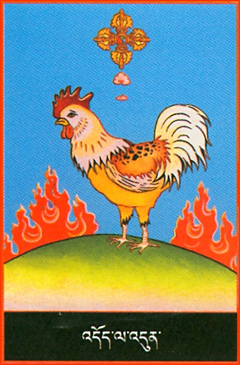

The Second Hindrance: Anger: Q&A with Lama Palden

I often find myself torn between lashing out at someone and trying to remain equanimous. I know it’s ideal not to explode in anger, but sometimes it still seems like the right thing to do—or like it would be “good” for me to express how I feel, directly. Is it ever right to let anger show?

When we are angry it may be important for us to communicate what we feel. But how we do this is critical. Simply blasting other people with our anger is not skillful or kind. We may think, “Well, they’re so thick-headed, I need to yell in order to get through to them.” But it’s difficult for people to take in what another is saying if they are being yelled at, because their defenses are instantly mobilized. They’re just as distracted by the reactionary thoughts going through their heads as we are by the force of our anger.

If we allow ourselves to calm down before addressing the situation, we can let go of our own defensiveness and anger. As we all have experienced, it is not possible to think objectively when we are in the throes of strong emotion. We need space to think clearly, to see what is really bothering us, and then to decide what it is that we actually want—and need—to communicate. We should take the opportunity to think through what is going on within ourselves, and imagine what the other person might be feeling as well. After we’ve given ourselves this critical distance from the situation, it’s possible to articulate what we want to say much more accurately and effectively. It is also more likely that we will be heard if we can deliver our message without triggering the other person’s defenses—or our own.

It’s understandable to feel better immediately after an initial catharsis: we’ve dumped our painful feelings onto another. But it’s not long before we feel worse, as our minds and bodies fill with the poison of anger, resentment, and, possibly, guilt or regret. We may try to cope with this miasma of feelings by going over the whole story in our minds again and again, talking about it with our friends, justifying our position and securing their support, planning our next attack, but these defensive strategies ultimately bind us further to suffering. When we feel that someone “deserves” our angry attack, we are indulging in hurting them in order to eradicate our own hurt—and hurting to get rid of hurt never works.

We suffer because we do not understand the openness of our true nature. This is the ignorance that the Buddha taught is the root of all suffering. The radiance of true nature is generated by compassion. The fortresses we construct around ourselves to ratify our position not only separate us from the person we’re angry with —but they also separate us from ourselves. The more we are cut off from our true nature, the more we suffer, and the less likely it is that others will listen to us. If we take the time to shift to a place where we can actually rest in openness and lovingkindness, our suffering diminishes. Anything that we feel needs to be communicated will naturally be articulated more effectively from this place.

Lama Palden is a licensed psychotherapist and a founder of the Sukhasiddhi Foundation, based in Marin County, California.

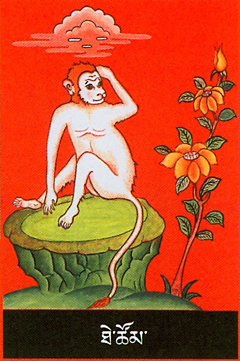

The Third Hindrance: Sloth, Torpor, and Boredom: Q & A with Ajahn Amaro

When I find myself with a free evening before me, I frantically try to fill it with activity rather than spending it alone. How can I learn to face an evening with nothing to “do”—and enjoy it?

Our sense of self is continually formulated by the things that we do and our interactions with others. When we find ourselves with nothing to do or no one to be with, our ego has nothing familiar by which to define itself.

However, we can transform our fear of this emptiness. Boredom and loneliness depend on investing in the sense of self. And, ironically, the harder we try to solidify our image of me through activity, the more we create the conditions for boredom to arise. If the sense of self is clearly understood as empty, solitude becomes a cherished companion. Try quieting the mind and then dropping the question “Who am I?” into it. A gap opens up after the question and before the thinking/self-creating habit can produce a verbal answer. Explore that gap and how it changes your experience of selfhood.

Sometimes I keep participating in something just because it’s comfortable, even though I’m not getting anything out of it: my relationship, job, even meditation practice. Is there a way to transform these feelings of sloth and apathy into newfound interest, or are they signs that I really am ready for a change?

We easily take refuge in the familiar because we enjoy the sense of belonging it brings; however, it is unwise to make a change reflexively every time these feelings arise. If we just sugarcoat our apathy with a new situation, we will never come to any real sense of fulfillment.

The Buddha recommended that in order to benefit from our engagements we need to ask ourselves, “Does this thing still have any genuine benefit for myself and others, here and now, or do I just keep at it out of habit?” Just that simple knowledge of the true effects of our actions is usually enough to guide us as to whether or not to proceed. If a change is needed, we shift our situation, guided by mindfulness and wisdom; if patient endurance is needed instead, that, too, will arise.

When I’m going through a difficult period, I often find myself doing everything I can to avoid the source of the trouble. I tend to become apathetic and even drowsy. Where can I get the courage to confront my problems?

From suffering, of course! If we can simply recognize that we’re distracted and that it’s because we’re avoiding something, that’s half the task.

Compulsive activity, blaming others, taking refuge in drugs or alcohol, and submitting to feelings of dullness in meditation are some of the ways that we evade our internal problems. These latter two are often caused by a desire to avoid feeling, because the litany of self-criticism is so painful.

The courage to confront the source of our problems usually arises from desperation. If we truly wish to be free of our difficulties, our heart has no other recourse than to acknowledge the core issue (even if we have studiously avoided it for decades!) and accept its connection to the suffering we are experiencing.

The other main source of assistance, when the heart is enmeshed in delusion, is the helpful perspective of our friends. Delusion has the unique ability to mask itself from its originator, thus it is often only from the “outside” that it can be recognized, and this recognition arouses the bravery needed for us to look squarely at the truth.

Ajahn Amaro is co-abbott of Abhayagiri Monastery in Redwood Valley, California.

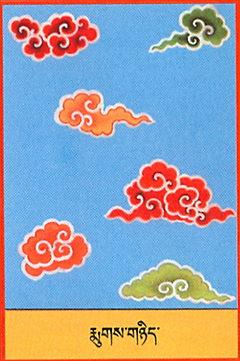

The Fourth Hindrance: Restlessness and Worry: Q & A with Michael Liebenson Grady

As soon as I’m in one place, or with one person, I want to be somewhere else, or with someone else. How can I learn to be satisfied with my current situation?

We are conditioned to seek happiness outside of ourselves. If only we could be in a different place, or with a different person, then we would be happy—or so we think. This conditioning generates a lot of restless minds interacting with one another, which in turn creates enormous disconnection. We need to be mindful of the state of mind that is driving our restlessness.

As soon we begin to feel even a little bit bored, many of us react by distracting ourselves with activity—any activity, however mindless: we turn on the television, call a friend, do the dishes. We may also feel we’re missing out on something better than whatever it is we’re doing. Both of these reactions ultimately stem from either aversion or greed. We need to learn to recognize our insatiable craving for new experiences. Being ashamed of our cravings doesn’t help, but justifying or denying them doesn’t help, either. Instead, we should learn to be with our situation as it is rather than moving away from it.

Acknowledging the feeling of boredom and then paying attention to our discomfort help bring the mind back to what is happening now. No doubt it can be difficult to be content with the present moment. But when we learn to open to the feelings that underlie restlessness, then meaningful connection with ourselves and others becomes possible.

Even though the circumstances of my outer life appear stable, inside I’m always second-guessing my decisions, worrying about what I’ve done in the past and what I should do in the future. Sitting practice brings me temporarily into the present moment, but as soon as I’m off the cushion, the worries flood back in. What can I do to prevent this?

To begin with, we should cultivate a friendlier relationship toward our worrying mind, rather than making an enemy of it. The nonjudgmental quality of mindfulness practice allows us to open to painful mind states such as anxiety without rejecting these energies or rushing in to try and fix them. With this attitude, we can then ask ourselves, “How can I work with this worry energy in a skillful way that will allow me to understand its nature?”

Our awareness that the mind is getting caught up in worrying indicates that we are on the right track. But it’s important not to stop at this level of awareness. Do we feel aversion to worry? Do we react by getting caught up in the other hindrances of discouragement, impatience, or self-doubt? With practice—both on and off the cushion—we can begin to taste the inner freedom that comes when we let go of our habitual reactions of clinging to pleasure and avoiding pain.

Sometimes, though, we are so caught up in our reactions to worry that we can’t seem to find the mental space to observe it. At these times, we can use skillful means to bring attention to the first foundation of mindfulness: the body. During sitting practice, focus your awareness on the sensations that arise from contact with the seat or floor. This will help bring the mind back into the present, and produce calm and inner balance. This practice sounds so simple—and it is! And yet, bringing awareness to the body at the times when we’re experiencing difficult emotions is often the last thing that we would think to do. With practice, working with the touch points becomes a very accessible and reliable resource for allowing us to be more present wherever we are and under any conditions.

Michael Liebman Grady has been practicing Vipassana mediatation since 1973. He is a guiding teacher at the Cambridge Insight Meditation Center.

The Fifth Hindrance: Doubt: Q & A with Sharon Salzberg

I make a point to keep sitting every day, but lately I’ve been asking myself what good it’s doing me, apart from the value of sticking to my commitment and the supposed benefits of spending time in silence and alone. How can I reinvigorate my faith in the practice?

Doubt and faith in our meditation practice often arise and pass away depending on what we are using as criteria for success. The first step is to try to move away from incessantly evaluating what’s going on in our practice. We need to be willing to go through ups and downs without getting disheartened. When doubt arises, try to recognize it as doubt, and realize that it is a constantly changing state.

If that doesn’t help, you might need to seek clarification about the meditation method you’re using, and perhaps make a change in your practice. You shouldn’t hesitate to ask a teacher or fellow practitioner about that. But in most cases, the doubt is simply a reflexive sign of our impatience.

This example is sometimes used to describe practice: It’s as though you’re hitting a piece of wood with an ax to split it. You hit it ninety-nine times, yet nothing happens. Then you hit it the hundredth time, and it breaks open. But when we’re hitting the wood for the thirty-sixth time, it doesn’t exactly feel glorious.

It’s not just the mechanical act of hitting the wood and weakening its fiber that makes for that magical hundredth moment, just like it’s not the physical act of sitting on the cushion that leads to realization—though both are certainly necessary. It’s also our openness to possibility, our patience, our effort, our humor, our self-knowledge. These are what we are actually practicing, no matter what happens or doesn’t happen to our problems, our moods, our sense of “being in the moment.”

Every so often I meet someone who seems perfectly congenial on the surface, but something in me just doesn’t trust them. This doubt ends up evidencing itself in my behavior, and sometimes causes hurt. When is it worth noting these feelings of doubt, and when is it best just to let them go?

It’s important to note a feeling of doubt that arises in a relationship. If we immediately attempt to let it go, we are automatically discounting our intuition. If you allow yourself to acknowledge the doubt and investigate its constituent feelings without judgment, a lot will be revealed.

You may notice that at its root are sadness, envy, competitiveness, or perhaps even echoes of a time in the past when you didn’t trust your intuition—with unfortunate consequences. In looking quietly at the doubt, you may decide it is largely a result of your projections onto the other person, or feelings of your own inadequacy, or jealousy.

As a result of this inquiry, you may resolve to behave differently. Or you may decide that there really is a disquieting element to the other person’s behavior that you don’t want to ignore. If it is the kind of relationship where you can communicate your feelings, it is worth trying to skillfully convey your discomfort to this person, and to listen to their response. If the relationship doesn’t allow for that, it is good at least to be aware of how your doubt might be clouding the ways you interact with that person, so that you don’t cause unnecessary hurt.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.