I told a friend I would be writing an essay about fear. He cautioned me, counseled me: “Don’t say that our fears are groundless.” He had heard me express the widespread opinion that in allowing ourselves to be governed by fear, we may be forfeiting our freedom.

Of course our fears are not groundless. Who would deny the threat of nuclear and biological war on our shores? And there are militant factions within three major religions that seem intent on fulfilling some prophecy of a final war between good and evil, certain that they and not their enemies are the children of light. What greater danger can be imagined?

But just for that reason it seems to me necessary to live without fear—to the extent that we are able, of course. This does not mean we should not protect ourselves from real dangers. It means we must be vigilant against the counsels of fear.

What impressed me most forcefully in the pictures from Abu Ghraib was how fear was employed as an instrument of torture. Humiliation too—but those photographs were meant to terrify, because they could be used to shame the victims in their communities.

Why has the discussion of these outrages very nearly vanished from public discourse? Does our silence bespeak a tacit consent to their possible continuation? If so, what would be our motive? I believe it is fear—fear of an elusive, treacherous enemy, but also fear of seeing the depths to which we may go for the sake of an equally elusive security.

I spent my formative years behind the Iron Curtain. It is commonplace to say the people there were deprived of their freedom. This is true, but it is a truth that was not evident to many of those people. If you live in a stooped position long enough you can come to mistake it for an upright stance.

I remember crossing the East German border after I had lived in the West for a while. There was an obvious external difference—more color on one side, more traffic, more flowers.

But the inner difference was less easy to identify. I called it freedom, as most people did. But remembering it now, I think that fear and the lack of it describe it better. There is no freedom without freedom from fear.

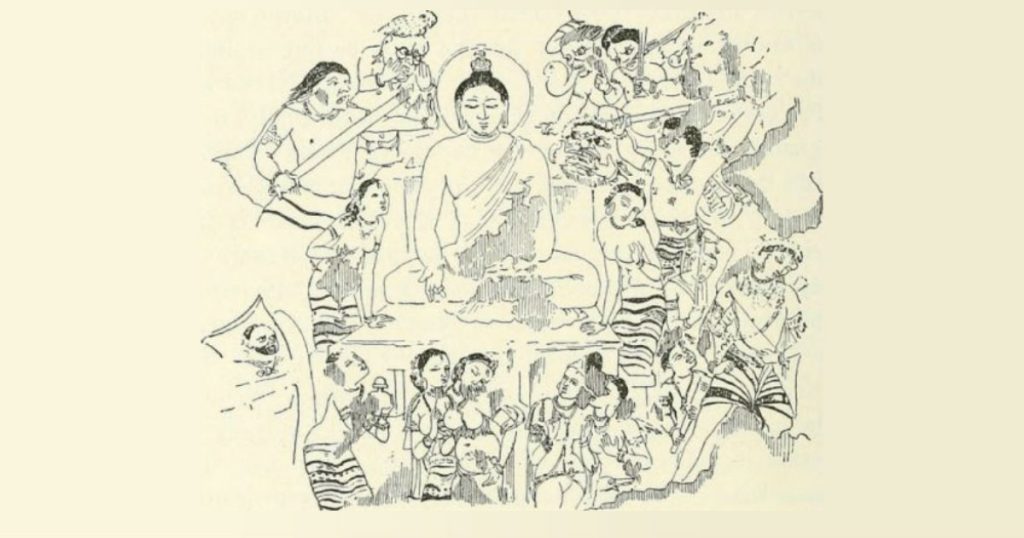

Of all the stories in the world’s religions, the one that inspires me most is the story of Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, sitting under the Bodhi tree, at the end of a path of austerity and fruitless searching.

A shepherd girl brings him a bowl of rice milk to restore his emaciated body, and he resolves not to rise until he attains Enlightenment. Mara, the Lord of Illusion, unleashes his armies—every conceivable terror, every death, every torment the mind can imagine. “O Mara, you cannot imprison me again,” Siddhartha says. “The rafters are broken, the ridgepole is sundered. I have seen the builder of the house.”

To us who live daily with some measure of fear, this example may seem too grand and too noble for practical emulation. But Siddhartha was a man, not a god, and what he did can be accomplished by ordinary people.

I have had much acquaintance with fear, and some with danger as well. There is a difference. This difference may be too obvious to mention, but it is frequently overlooked.

Fear is a product of the mind. And danger can be met without fear. Surely soldiers in battle know about this. There is no greater enemy than fear.

♦

Abridged from an essay that originally appeared in the Los Angeles Times on December 13, 2004. Joel Agee’s most recent book is In the House of My Fear, a spiritual autobiography.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.