Life is a performing art. So is Buddhism.

Zen practitioners, intent on taking care of the Buddha all around them, honor everything as worthy of keen attention. They express this through precise and formal ways of bowing, eating, washing, entering the meditation hall, sitting on cushions, rising, and moving through the day. Much of this is accompanied by rhythmic sounds and wafting incense. Iconic music or percussion, patterned movement, and chanted speech are among the ritual elements commonly found in traditional Buddhist communities.

While modern Westerners in the last 50 years have grown increasingly curious about Buddhist practice, for many curiosity and practice often halt at the shores of ritual performance. For such people, ritual performance seems in tension with modern modes of self-expression and identity. As a modern person who is quite immersed in Buddhist tradition, I wonder how we might draw on our modernity while also coming to appreciate ritual engagement.

Rituals are not unique to antiquity, of course. They govern modern secular behaviors, too—from Super Bowl halftime events to TGIF exuberances to pride parades to how we eat meals with friends and family. When we feel in tune with ritual expression, its social cohesion and choreographed activity affirm our sense of belonging and being. In Buddhist and other spiritual communities, ritual expression provides support for very personal inner work.

Yet for contemporary people, traditional rituals might not feel so nourishing. We moderns are more likely than traditional peoples to experience orchestrated behaviors as compromising our right as individuals to act and believe as it seems right to us. What’s more, we tend to believe that our own unique perspective should override inherited ones. Through this lens, ritual can seem superstitious and in tension with our cultural deference toward reasoned logic. Ritual seems to ask us to believe things that we just don’t believe and to do things we don’t ordinarily do. Why bow if you don’t believe in what you’re bowing to? Or if you just don’t feel like bowing?

Even for modern Buddhists who are quite devoted to ritual practices, such objections have a way of showing up. They do for me. For more than four decades I’ve practiced Tibetan Buddhism, yet I still find that questions about the bona fides of its ritual forms will on occasion—and especially while I’m on retreat—roar out of me. Part of me isn’t down with the program. Part of me protests, observing wryly that I am, after all, an educated person, aware that it’s foolish to feel you can just appropriate other cultural forms. I’m keenly aware of how absurd this activity would appear to many people I know, like, and respect. But I also recognize that these protests don’t begin to reckon with the new vistas this practice is actually offering me. This is because, even as these protestations continue to resurge, the enrichments of ritual practice keep coming.

I have begun to think that in some profoundly contemporary way my protests and enrichments are actually in fruitful dialogue with each other. The result? So far I’ve always emerged profoundly grateful to have stayed the course and to have, despite bouts of inner backlash, followed a calling that includes ritual practices; for they open doors nothing else in my experience has opened. This doesn’t mean I encounter such practices as a traditional Tibetan would. The simple fact of my resistance, grounded in cultural assumptions that traditional Tibetans never encountered, puts me, along with fellow practitioners with similar background and experience, in another ballpark entirely. We can’t not be modern.

Since the time of the Buddha, practice and teaching have involved dialogue. The outer dialogue between students and teachers mirrors and provokes practitioners’ inner dialogue. For contemporary practitioners like me, this dialogue is especially beneficial when it provokes resistance while also recognizing rewards. Not getting stuck in either is a modern middle way. It is as profound and subtle in its way as ritual practice itself. So I’m interested in reflecting on the sources and styles of modern resistance. I’m especially interested in the counterintuitive possibility that such inquiry is a path to fruitions that are at once born of tradition and unique to our modern situation.

Ritual practice engages the whole person. This idea of wholeness is already in tension with the mind-body divide that is a marker of modern cultural inheritances. The encompassing richness of ritual involves all our senses. Its riverlike eddying gently reshapes and throws into relief the boulders, so to speak, that mark the territory of our current cultural landscape. Going the other way, the practice-river itself is reshaped by such boulders, even as it stays true to its nature as water. Meeting this resistance seems to yield its own rewards. It makes our contact with the water of our being more precise and palpable. Our individuality and modern sensibilities remain, while at the same time the disconnection we feel between modernity and tradition palpably softens.

From our modern vantage point, ritual gives us a chance to hone skills of wonder-filled inquiry. In wondering, we come alive, released from judgment, keen to know just what happens in our body, mind, and imagination as we bow, chant, or imagine sending out sound and light. Tibetan ritual practices are meant to challenge our ordinary perspective, whatever it is, and to challenge it profoundly. For modern Buddhists, however, they are also challenging in a different way. They are challenging not simply because they are profound or foreign but also because they require or presume skills that our modern education does not develop.

Ritual’s operative premise is that physical and imaginative gesture, including the movement of energy in and beyond the body, will reshape our lived experience. This happens because body and consciousness are both impacted by such performance. They are both impacted because they are waves in the same ocean of experience. The body is not just the material container for mind, and mind is not just a witness to the body. Such wholeness is not altogether foreign to our experience, however modern we may be. Whoever we are, we discover moments when the divide between self and world, mind and body, as well as between ancient and modern voices within us, can soften.

What’s worth noting is that living too much in our heads, as most moderns do, is impoverishing. Addressing this tendency is as necessary for ritual practice as it is for healing certain lacunae in modern life. In both cases it means going against the objectifying grain of modern culture to acknowledge waves of enrichment that start to flow as we deepen our capacity to be more present to lived experience, to recognize our own subjectivity and our multiple styles of knowing—sensory, intuitive, and so forth—as resources for exploring inner and outer worlds. After all, consciousness is the one phenomenon that embraces the whole of our experience. Any all-embracing ritual is poised to make us aware of this lived wholeness, but only if we can sense what our experience is.

Our mind wanders incessantly, but our body and senses are always in the present. To investigate our embodied experience is to investigate the living present. Practitioners orient toward precise observation of how a specific ritual in a specific session challenges, changes, or otherwise impacts us. This, in my view, is one of the most important—and modern—learning curves for bringing meaning to ritual practice. If we are lucky, this process surfaces patterns that until now were invisible. Patterns brought to awareness run the full range of common habits of procrastination, lack of self-worth, anger, and rigidity. Seeing these is essential for getting to the next layer of ritual efficacy, where our cognitive and somatic inquiry is specifically informed by Buddhist perspectives.

Those Buddhist perspectives see all patterns, as well as the nuanced sensations associated with them, as expressing our extremely subtle holding-on to the kind of reified “me-ness” that is, for Buddhists, at the crux of the great illusion that practice is meant to dissolve. Those feelings of me-ness vary widely from culture to culture. Yet Buddhist ritual practices aren’t aimed just at challenging the particular expressions of I, me, and mine; they challenge as well the core constellations of me-ness that animate those expressions in whatever guise they arise. Even to understand what me-ness feels like takes patience, time, and attention. So ritual practice is challenging because of the subtlety of its reach even more than because of how it disrupts cultural norms. Everyone needs to thread their own, very personal way through this intimate labyrinth. The form is the same, but the journey is not.

It takes time for ritual practice to become intimate. It requires sustained attention and patience, both of which go against the grain of contemporary life’s breakneck pace and culture of wholesale distraction. What’s more, the repetition ritual entails may feel anathema to modern ideas of individual expression and creativity. But repetition is key to ritual’s transformative power.

Repetition is what allows something brand new to occur. Repetition, like the lapping of ripples against a rock, gently shifts the ground on which we tread, and so alters our relationship to the things we experience. It changes our relationship to experience itself. As Kierkegaard observes in Either/Or, “One may have known a thing many times and acknowledge it . . . yet it is only by the deep inward movements . . . that for the first time you are convinced that what you have known belongs to you.”

Repetition is what allows something brand new to occur. It gently shifts the ground on which we tread, and so alters our relationship to the things we experience. It changes our relationship to experience itself.

In this way, formal ritual elements become great sources of support. Ritual repetition is roughly analogous to scientific controls. We sense shifts in our experience more clearly against the backdrop of sameness that is formal repetition. We notice, for example, how very differently we experience practice at different times, even as the form of what we do remains the same. In this way we touch, as if for the first time, the emergent power of something already inside us.

Like life, ritual is both repetitive and unique. The spiritual challenge in life, as in ritual, is to stay current and awaken to our own rote habits of perception and reactivity in thought and action. Ritual helps to dissolve these habits—not overnight, but over time—and also helps us to evolve such positive qualities as serenity and genuine responsiveness. Both the dissolving and the evolving leave us with more space in our lives, in our hearts, and in our minds.

Tibetan ritual practices are fundamentally processes of dissolving and evolving. In this they correspond to the basic meaning of “enlightenment,” which is rendered by two syllables in Tibetan. The first is byang, meaning to cleanse, eliminate, remove; hence, dissolve. The second is chub, meaning to grow, blossom, further, develop; hence, evolve. Practice aims to do away with what impedes and bring forth what furthers. There are ritual gestures for dissolving impediments such as distraction and there are those for evolving qualities such as relaxed attention. Often the same gesture is used for both. “Enlightenment” is a name given to the simultaneous culmination of both arcs of practice.

The flow of ritual carries us toward a horizon that is both vast and intimate. This combination is crucial to the transformative power of practice. At this horizon we find a perfect complementarity of dissolving and evolving. Wrongheaded senses of me-ness finally begin to ebb, and as they loosen their grip on our lives, other qualities—of trust, joy, real connection, and love—emerge.

Ritual practice is more about what we do than what we think. We don’t have to intellectually determine that Tara is an actual being who, as the story goes, practiced for aeons in order to display female Buddhahood. We don’t have to reject her either. We don’t have to decide anything. In the liminal space of the human imagination we can simply hear the story and let it resonate for us, open a door to some capacity for spacious tenderness that we didn’t know we had. And I believe this is close to the way traditional peoples regard such tales. That is, while perfectly aware of the difference between real-world functioning and fantasy, traditional practitioners are not perpetually on the lookout for a place to draw the line between facts and other felt realities, or between an objective, external world and a subjective, internal one. To consciously abide in that spacious undecided realm is to allow ourselves to be touched by our own practice in very deep ways. We can enjoy Tara’s presence, for example, and grow to more fully inhabit her/our qualities in a way that is palpable in mind and body. At the same time, in bowing to Tara we are bowing to the enlightened tenderness already within us. We are not surrendering to a fiction; we are present at the dawning of something new in our own experience.

Ritual thrives on the rapt attention that some call faith, and inspires it as well, yet faith can seem a bridge too far for many moderns. We are heirs to a mind-set that radically distinguishes between rational and emotional experience. We have established firewalls meant to preserve a kind of personal space and freedom. But while some of this is for the good, it also supports unduly rigid ideas of what “faith” means. The Tibetan word that gets translated as “faith” (dad pa) does not mainly mean belief; more significantly it suggests receptivity, openheartedness, and the capacity for taking delight in what inspires you. This kind of faith makes possible a rich relationship with the nuanced layers of ritual practice. It opens you to the outer and inner dialogues of renewal. There’s something like a call-and-response momentum: you gesture, or chant a sound, or bring forth an image, and doing this calls forth a response in you that you then bring into the ritual, and you grow more inspired as a result. This iterative process teaches you something about the wheel of your own reaction patterns and the sense of me-ness around which they revolve.

Within Buddhist traditions as I’ve known them through living and studying with Tibetans in India, Nepal, and the United States, and to a lesser degree in Theravada contexts, there is no absolute requirement to argue things out and come to an institutionally approved conclusion. Meaningful commitments of all kinds, including intellectual reckoning, must come at an organic pace. Moreover, ritual is done with a different kind of intelligence, not strictly rational, yet still holding a coherent logos. We don’t have to sort out the extent to which we “believe” in Tara and her narrative in order to feel that when we bow to her we are honoring something profoundly inspiring. The naturalness of the qualities evoked contrasts with and can soften the attitude, shared by many moderns, that such ritual gestures are foreign or imposed rigidly.

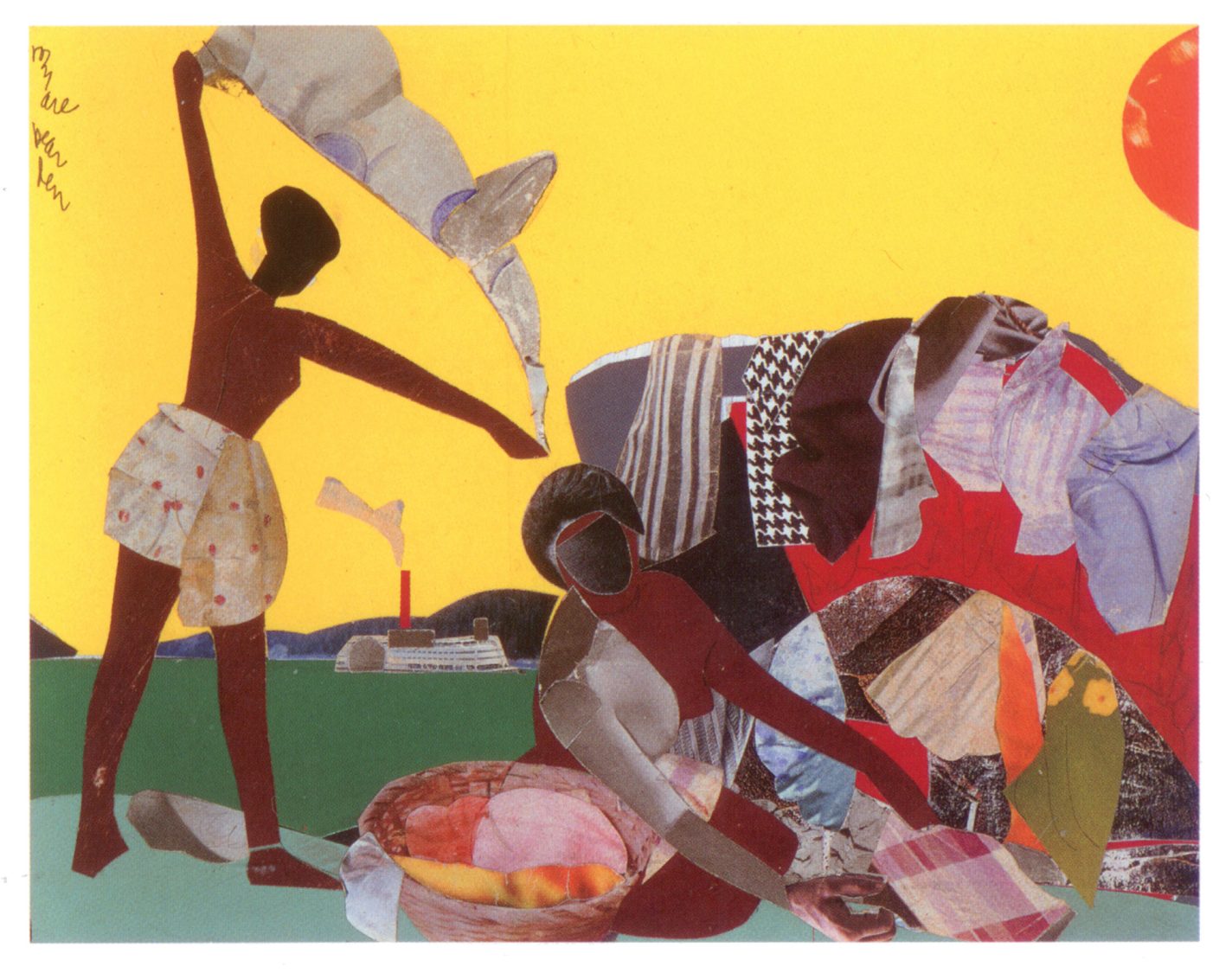

Our relationship to art opens in similar ways. We respond to what we see, not what we decide. For example, Michelangelo’s Pietà in the Vatican is Christian religious art, yet it also expresses something of universal human appeal. Whether or not we believe in Mary’s virginal motherhood as a literal fact, we can be touched by the tenderly human love in her face. And in that moment, we recognize what love feels like. We have touched something that is both human and spiritual, and that lies at the heart of the main strands of our world’s religious traditions.

The cohesiveness that embraces the full spectrum of ritual—as seen through traditional Tibetan eyes, at least—is not a small thing. It is not a small thing particularly in view of the contemporary rhetoric that divides “the spiritual” from “the religious,” another demonstration of the distinctly modern suspicion of ritual. Institutional power versus personal freedom is pivotal to this dichotomy, in which religion is associated with institutions while spirituality is something belonging to the individual. The issue of personal freedom takes center stage. Ritual certainly, in some contexts more than others, expresses institutional power and authority. But to call it “religious” rather than “spiritual” just extends the purely modern assumptions and attitudes on which this divide rests. Buddhist institutional power in the modern era, especially in the West, is nothing like the power that Christianity, for example, had and still has in many parts of the world. In the West, such power is marginal at most, and it is individualism that, more than any Buddhist institution, dominates nearly everyone’s experience. Contemporary Western Buddhists usually practice and teach in situations with comparatively loose ties to institutional tradition, even when personal connections with teachers and lineage transmissions are very strong.

The split between religion and spirituality seems of little help in navigating our current landscape as it relates to traditional or contemporary Buddhist practice. Indeed, it skews our perceptions in a way that is directly related to our feelings about ritual. This distraction itself is a bulwark against the kind of oceanic wholeness that gives ritual its logos and fruition. Distraction is often simply the wave’s protest against submersion into that ocean. And it’s not a bad strategy. Distraction definitely protects us from experiencing the extent to which our own individual and culturally derived self-structures are challenged or furthered by Buddhist practices. This challenge, and the dissolving associated with it, is at the very heart of our concern as evolving practitioners.

But as moderns we also have a different set of concerns, especially concerns about personal freedom. Will Buddhism help me creatively figure out my unique individual way of living? Or will it bind me, as religion can and often does bind us, to stale ways of thinking and acting that thwart and diminish me? These are real concerns, but answering them by dividing spirituality and religion does not do justice to the situation. The Latin root of religion has been interpreted as meaning “to re-read”—and ritual is indeed a profound rereading of self and world. It has also been interpreted as meaning “to choose again,”—that is, to seek more deeply into spiritual matters. And the same root has also been translated as “to bind,” as in being bound to the sacred or to the Church or to God. So the binary of spiritual-religious is actually contained in the different interpretations of the word religion itself. Traditional cultures (Buddhist and otherwise) that don’t really have a word equivalent to the term religion make no distinction between being spiritual and being religious. Everyone is both. Spirituality is an aspect of religious life, and religion is an integral part of who one is.

Across Asian Buddhist traditions, perhaps most notably in Zen and Tibetan communities, bowing is a vital practice. To moderns unfamiliar with this practice, it can seem an unduly extravagant gesture bordering on the embarrassing, and reeking with quaint notions of hierarchy, formality, and obedience. In context, however, it is not an expression of either submission or flattery. To bow is to make oneself at home in a relatedness that is, for Buddhists, the most generous experience of what it means to be human. Bows express an openhearted orientation to the ever-expanding horizon of our own possibility. Bows express deep love. Experiencing or interpreting them this way, however, engages belief patterns that are neither scientifically nor logically verifiable. The logic of bowing is more poetic than rational, but it is a logic nonetheless. Beyond this, the surrender expressed in bowing seems antithetical to the character of a real individual. Yet at a deeper level, our very individuality calls forth a longing for it.

Related: Shunryu Suzuki Roshi on Bowing

Indeed, beyond anything else that ritual accomplishes, it provides a sense of belonging. A group bonds via a sense of shared identity that itself is experienced as a profound support for the work of living, the work of the path. The most fundamental rituals of Buddhist practice, refuge and compassion, also invite the sense of a great participatory milieu of beings seen and unseen. This cohort, once meaningfully incorporated into one’s identity as a practitioner, can seem at once nourishing and threatening. Our individuality may sometimes feel supported and at other times feel thwarted through such engagement. This itself is not a trivial issue of the Buddhist path. When a wave blends back into the ocean or when the misconstrued small self dissolves into reality, are these diminished or expanded? In other words, what is the nature of surrender in Buddhist practice and ritual?

The Canadian psychoanalyst Emmanuel Ghent described human yearning for surrender as a “longing for the birth, or perhaps rebirth, of true self.” His description is uncannily apt for practicing Buddhists. We bow to the Buddha, dharma, and sangha, each of which models and teaches utter surrender of false styles of me-ness. We bow past our narrowness and obstructions and to the vast sky of our being.

Rituals are framed by a beginning, middle, and end. This frame provides the very sense of completeness and coherence that life so often lacks. In every ritual phase, we are meant to embrace elements that are part of this larger whole through repeating moves of dissolving, like the melting of hatred, and moves of evolving, like the emergence of love. Through repeating these gestures, we gain greater facility until we finally get them right. Or righter. As we keep getting second, third, and umpteen chances, we begin to sense that even when we get it wrong, there is a fundamental and naturally stainless arena in which everything—the right and the wrong—takes place. Even our worst mistakes do not obstruct its presence, or our returning to awareness of it.

As the great Tibetan teacher Longchen Rabjam (1308–64) says in his discussion of Madhyamaka in Precious Treasury of Philosophical Tenets, primordial wisdom is the nature of all things. This wisdom is no different than the enlightened state itself. It suffuses everything. Most especially, he notes later in the same text, this wisdom is present in every aspect of the rituals of Secret Mantra. Wisdom is oceanic, meaning that dissolving into something well beyond the personal individual is a central goal of ritual practice. Thus, many rituals in his lineage are explicitly oriented toward bringing practitioners into a lived experience of this embracing quality of wisdom. In entering such a ritual, we do not ask ourselves whether we believe in Buddha or Tara. We ask whether the rituals that express our connection to beings who embody exactly the qualities we seek are in fact helping such qualities to awaken. We ask whether, over time, our obstructive responses dissolve and make space for desired qualities to evolve. In Buddhism, love is the ultimate solvent of what obstructs and also the culminating fruition of what evolves. In a real sense, every gesture of ritual has the potential to express and give rise to it.

The power of ritual does not lie with facticity. It thrives on keen phenomenological awareness, on a relaxation of the structures of ordinary sensibility. A vital key to ritual power is to remain present to our embodied experience. Neither mind nor body can navigate this journey alone. The wholeness in which they mutually participate is assumed, not discussed, in Buddhist practice. Moderns, however, must discuss it in order to taste it. Tasting is essential. Dialogue across all our personal and cultural divides is as important and potentially healing as addressing the divide most emphasized traditionally in Buddhist thought and practice: the apparent abyss that separates you and me, seer and seen.

Finally, after many repetitions, ritual becomes a performance of our deepest knowing of self and world. Like rehearsing artists, we hone our expressive skills until our practice of compassion, wisdom, and wholeness becomes the real thing. We revisit the gestures of ritual again and again until we gain the force of habit to carry our seeing and being with full-hearted and loving generosity into the hurly-burly of everyday life. Modern life. For our release, like our rituals, happens nowhere other than right in this time and in this precise place.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.