After finishing her morning cup of coffee, Amy Chavez laces up a pair of lime green and gray running shoes to begin her morning jog. She pushes open the back door of her seaside home and steps onto the Shiraishi Buddhist pilgrimage route, a 400-year-old sacred trail that wraps around Shiraishi Island in western Japan’s Seto Inland Sea.

On this warm September day, she has agreed to guide me around parts of the trail to show me life outside of Japan’s dense cities. While Chavez knows the 5-mile trail like her own backyard, it has been slowly going to seed—a relic of a time long passed.

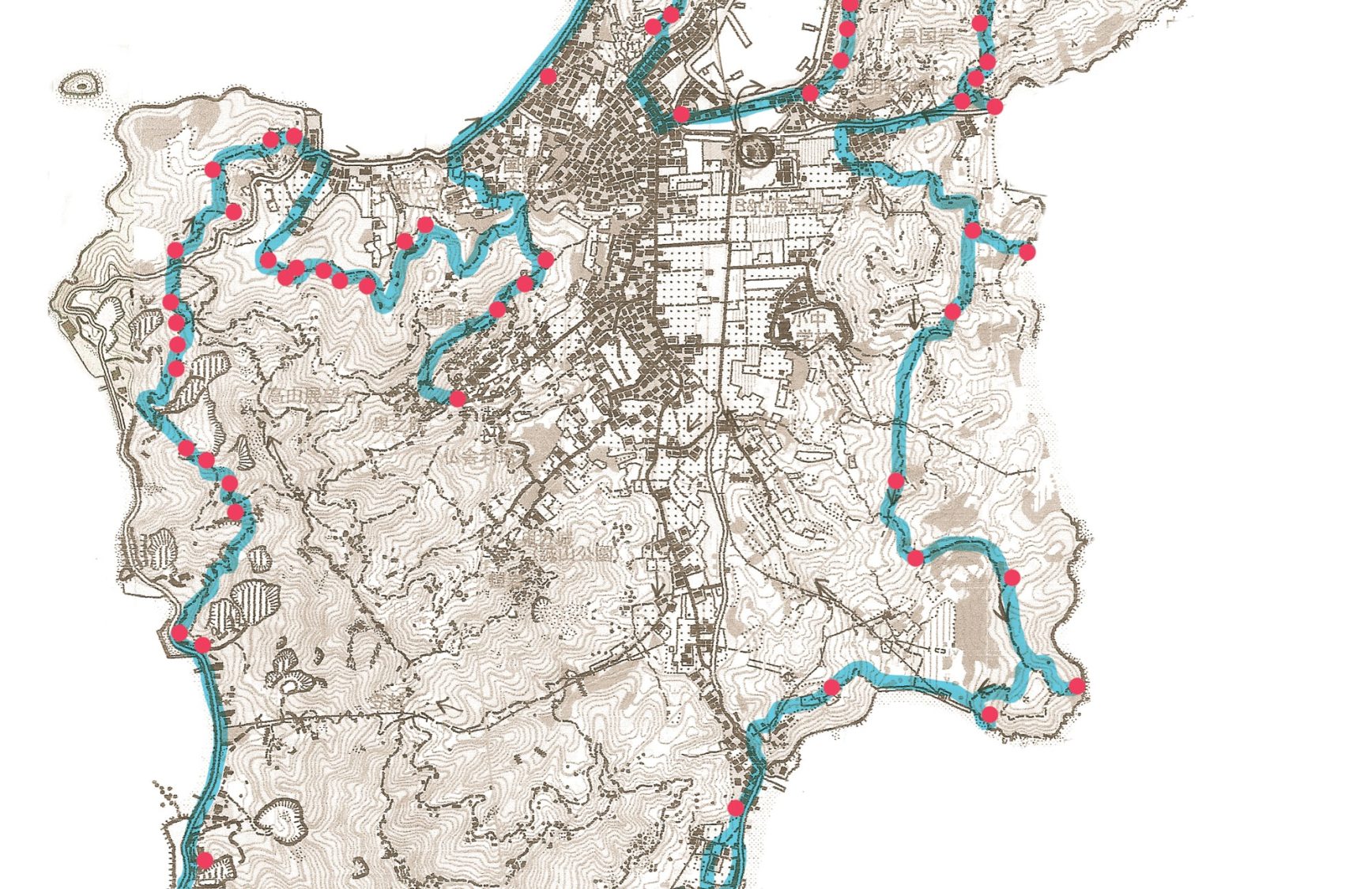

Shiraishi Island’s pilgrimage route is a miniature replica of the Shikoku 88, one of Japan’s most revered pilgrimages. The route stretches 1,200 kilometers (746 miles), connecting 88 temples, shrines, and other sacred sites on Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s four main islands. Both the Shiraishi and Shikoku routes trace the footsteps of Kukai (Kobo-Daishi, 774–835), founder of the Shingon school of Buddhism, whose statue has been placed in several spots along the route to guide pilgrims. In the past, Japanese followers usually walked the Shikoku 88 upon retirement or when they were able to take time off. Walking the pilgrimage can take six weeks or more, but in recent years, bus tours that cover the route in only a few days are a far more common way to complete it. The much smaller Shiraishi pilgrimage, on the other hand, allows visitors to finish the 88-temple circuit on foot in one or two days.

While the Shikoku pilgrimage has gained some popularity among tourists thanks to books and a few recent television reports, the Shiraishi pilgrimage has not enjoyed the same luck. Parts of the trail remain walkable, but large stretches are in dire need of repair.

Many towns throughout Japan have been impacted by depopulation in the countryside and the gradual decline of jobs like fishing and farming. Japan’s island communities are often hit the hardest. The population of Shiraishi declines every year: currently it numbers a little over 500, compared to about 700 residents 10 years ago and 900 residents 20 years ago.

“From the standpoint of the island community, this is sad,” Chavez says, “but even more poignant is the loss of Japanese culture that will go along with it.”

During our run, Chavez points to fallen trees, weeds, branches, vines, and natural potholes that block several sections of the pilgrimage. Signage indicating the way to some of the shrines or temples is nonexistent or severely lacking—without Chavez, I would be lost. One part of the path requires visitors to use a rope to get to one of the route’s shrines, and many of the natural pathways, once clearly defined, have become dangerous to walk on. Chavez tells me that several island residents who used to tend the path gradually stopped participating in cleanups as they got older. And so each year the path that was once a vibrant and essential part of Shiraishi’s identity fades further from physical view—and from memory.

Yet Chavez is determined not to see the pilgrimage disappear before her eyes, even if she is one of only two foreign residents living on Shiraishi (the other is her husband, Paul, an Australian). In May 2015, she organized the Run with Kobo Daishi Trail Race, the first running event to take place on the island; it raised $2,500 to help maintain the trail and increase awareness of Shiraishi’s pilgrimage.

Though programming difficulties prevented holding a race in 2016, Chavez hopes to make the run an annual event beginning next year. Her eventual goal is to raise about $10,000 a year to keep the path and signage well maintained so that tourists and native Japanese can more easily discover and follow the trail. She also coordinates school visits to the site to encourage students to pitch in. A petite blonde with a thin frame, Chavez is resolute in her words and mission. She speaks slowly and clearly, with only a hint of a Midwestern accent to echo the formative years she spent in Ohio.

“My goal here is to preserve some of Japan’s ancient traditions,” she explains. “These days UNESCO is literally saving places, keeping them on the map with their designations of world heritage sites. Japan itself has also designated national treasures. There are other precious traditions and relics in places like Shiraishi Island that are just as important, but that will never get the attention they deserve. The Shiraishi pilgrimage is one.”

Chavez’s fondness for pilgrimages goes back decades. She became interested in Japan’s ancient pilgrimages when she was unexpectedly laid off from her position teaching English in Okayama city in the late 1990s. By that time, she was already living comfortably on Shiraishi Island, where she could commute to the city for work but reside closer to nature. Yet without a job just as she entered her midthirties, she questioned her future. Should she stay in her adopted country, which she had loved so dearly but now felt distant from, or return to America?

Chavez, a devoted runner, decided to go on a long run to think through her problems. It turned out to be the longest run of her life. Budgeting $1,000 (about $30 per day) and taking along only essentials in a small backpack, she set out to run the entire 746 miles of the Shikoku 88 temple pilgrimage in March 1998. By the end of her 31-day journey, she was covering 20 to 30 miles a day.

Throughout the trip, as Chavez repeatedly encountered the generous hospitality the Japanese are known for—local residents often offered her free food or shelter when they learned what she was doing—the pilgrimage reminded her of why she had originally fallen in love with Japanese culture. And although she didn’t begin the pilgrimage with particular expectations of what it would do for her, Chavez says she “gained incredible insight into life and my own person as well as into the lives of others I met along the way.”

“A six-week pilgrimage is an incredible opportunity to quiet the heart and soul and to open up to change,” she continued, “even if you’re not looking for or thinking you need change.”

Since finishing the Shikoku 88, Chavez, now in her fifties, has completed several other smaller pilgrimages throughout Japan. She often writes about these journeys as a columnist for the Japan Times and is the author of several books on Japanese culture. Besides promoting the Shiraishi pilgrimage, she encourages tourists to explore the island, where she and her husband now operate a guesthouse and seasonal bar. The pilgrimage remains a central part of her life in Japan, and she continues to run the route regularly.

As Chavez and I continue our own run on the Shiraishi pilgrimage route, we travel through a thick green bamboo forest and climb a 400-year-old stone staircase that leads to Kokubunji, the 80th temple along the route. Every so often, Chavez pauses to clear away branches, leaves, and overgrown weeds, revealing paths that lead to more Buddhist statues. After about 40 minutes of running, we push farther uphill until we reach a peak overlooking the sea. The reflection of the sun shimmers on the translucent blue water, and we pause for a moment to take in the view before heading home.

“People have been doing this pilgrimage for over 300 years, rejuvenating themselves, praying to their ancestors, confronting the deaths of loved ones, and considering their own mortality,” Chavez says. “We need places in nature like this that encourage us to think in such a framework, to think more deeply about our lives and our society.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.