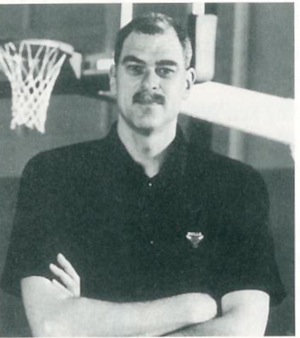

Sacred Hoops: Spiritual Lessons of a Hardwood Warrior

Phil Jackson and Hugh Delehanty Hyperion: New York, 1995.

256 pp., $22.95 (cloth)

On Phil Jackson’s first trip to New York as a professional basketball player, he was driven into the city by Knicks coach Red Holzman. On the way, someone threw a rock at the car and smashed the windshield. After determining that nobody was hurt, Holzman turned to the gangly rookie and said, “Well, that’s New York City, Phil. If you can take that, you’ll do just fine.” Jackson learned a valuable lesson from his new coach: “Don’t let anger—or heavy objects thrown from overpasses—cloud the mind.” For more than a quarter century, Jackson has continued to struggle toward awareness. While many coaches openly credit Christianity for their victories, the highly successful coach of the Chicago Bulls may be the only American coach to openly acknowledge Eastern influences.

“The point of Zen practice is to make you aware of the thoughts that run your life as they arise and diminish their power over you,” he writes in Sacred Hoops. “The more skilled I became at watching my thoughts in zazen practice, the more focused I became as a player. . . . I also developed an intimate knowledge of my mental processes on the basketball court.”

As a player, Jackson was a curiosity, a gawky long-armed defensive specialist who was not afraid to do the dirty work on a talented team. Even then, the press and the fans knew he dabbled in the “counterculture.” Jackson was trying to find an alternative to the benign Christianity practiced by his father and the more rigid Pentecostal Christianity of his mother.

Jackson’s upbringing in North Dakota and Montana gave him a deep respect for Native American spirituality. An older brother later introduced him to Zen during the off-seasons, and when Jackson’s first marriage broke up, he moved into a loft in Manhattan and became friendly with a “lapsed Catholic turned fundamentalist Muslim named Hakim.” On road trips, Jackson was reading books on spirituality and sitting with Zen groups.

After his playing career ended, Jackson feared he might have been labeled too much of a “Maverick”—the title of his first book—to be given a coaching job in the National Basketball Association. He was surprised to have the job as head coach of the Chicago Bulls land in his lap in 1989. Jackson began applying his vision to his players right away. He led the Lord’s Prayer before games and practices. He placed Lakota Sioux artifacts in the team’s meeting room. He quoted Scripture or the Tao Te Ching. He also passed out books with spiritual messages: Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mindto the open B. J. Armstrong; Way of the Peaceful Warrior to Craig Hodges, a convert to Islam; and Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance to the bemused John Paxson. One day he even had the entire team meditate together. The skeptical Michael Jordan—probably the greatest player in basketball history—glanced around, stunned to find some of his teammates were actually taking it seriously. “It’s easy for players to get so caught up in the fantasy world of the N.B.A. that they lose touch with reality,” Jackson writes. “My job, as I see it, is to wake them out of that dreamlike state and get them grounded in the real world.”

Jackson quotes the Tibetan Buddhist teacher Chogyam Trungpa: “The challenge of warriorship is to step out of the cocoon, to step out into space, by being brave and at the same time gentle,” and adds of his own “hardwood warriors” that “their first instinct was to use force to solve every problem. What I tried to do was get them to walk away from confrontations and not to let themselves be distracted.” The result was impressive: the Bulls won three straight championships. But Jackson admits he has failures. Many of the players move on, seeking more money, more playing time, more status. Last year Jordan came back from a year-and-a-half “retirement,” and Jackson could not reintegrate his exceptional talents with the rest of the team in time to win another championship.

There is probably more basketball than Zen in this book, but Jackson never pretends to be an expert. The voice sometimes sounds less like Jackson than the neutral as-told-to style of co-writer Hugh Delehanty, and the transitions are not always smooth, but Jackson’s tales of Jordan and company will draw readers into this pilgrim’s story. At very least, the next time readers see Phil Jackson glowering and waving his long arms in front of the Bulls’ bench, they will know there is a complicated and curious wanderer behind those gestures.

George Vecsey is a sports columnist for the New York Times who previously covered religion.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.