When we read the account of the Buddha’s last night, it’s easy to sense the importance of his final teaching before entering total nibbana: “Now, then, monks, I exhort you: All fabrications are subject to decay. Bring about completion by being heedful.” These words call attention to themselves because they were the last he ever said.

That may be why it’s so easy to overlook the importance of what the Buddha did right before saying them. In a gesture extremely gracious—given that he had been walking all day, had fallen severely ill along the way, and now was about to die—he offered one last opportunity for his followers to question him.

Then the Blessed One addressed the monks, “If even a single monk has any doubt or indecision concerning the Buddha, Dhamma, or Sangha, the path or the practice, ask. Don’t later regret that ‘The Teacher was face-to-face with us, but we didn’t bring ourselves to cross-question him in his presence.’”

When the monks remained silent, he repeated his offer two more times, and then proposed:

“Now, if it’s out of respect for the Teacher that you don’t ask, let a friend inform a friend.”

When they still remained silent, he explained their silence to Ananda:

“Of these 500 monks, the most backward is a stream-winner, not destined for the planes of deprivation, headed to self-awakening for sure.” (Digha Nikaya 16)

It’s possible to read this passage simply as a rhetorical flourish, indicating how special the assembly was that had gathered to witness the Buddha’s passing: only those who had had at least their first taste of the deathless were privileged enough to be present. But the passage goes deeper than that, showing how the Buddha had brought them to that taste. Instead of enforcing an unquestioning acceptance of his teachings, he had resolved his students’ doubts by being open to their questions. The fact that this incident is placed right before the last teaching is a measure of how central this method was to his teaching and how important it was to his followers who assembled the canon.

The reason for its importance may be connected to the fact that the Buddha’s teaching starts not with a first principle but with a self-evident problem: how to put an end to suffering. And instead of trying to argue from this problem back to first principles, he stays focused on the immediate question of how to solve it. As he noted, suffering gives rise to two responses—bewilderment and a searching question: “Who knows a way or two to stop this pain?” To help put an end to that bewilderment, the Buddha presented his teachings as responses to the many questions deriving from that primal, searching question. Thus questions formed the primary mode for organizing what he taught.

It is important to note that the Buddha didn’t answer every question that came his way. He’d answer only those questions that were relevant to the problem of suffering. In fact, the way he handled irrelevant questions was an object lesson in how to frame useful questions. Furthermore, because these questions were aimed at solving a problem, the questions the Buddha was open to answering—and that he suggested his listeners should ask themselves— operated on three levels.

The first level aimed at giving shape to their ignorance: to clarify their felt need to put an end to suffering, and why the Buddha’s proposed solution made sense. Questions of this sort are like the shape of a missing piece in a puzzle: only a piece that matches the shape of the puzzle will fit. The second and third levels were aimed at determining whether the Buddha’s answers actually solved the problem, with the second level establishing tests for checking whether his answers actually worked when put into practice, and the third level setting standards for measuring whether an answer actually passed the tests—in other words, determining what it means to “work.”

The reason we need questions to give shape to our ignorance is that the shape helps to narrow down the range of potential answers we’ll need to test to see if they fulfill the function we want. It’s a way of saving energy and time so that our second and third levels of questions can be applied immediately to the most promising candidates. If none of the possibilities suggested by the shape of the first-level questions pass the second or third levels, we can turn around and question the puzzle with which we started: maybe the shape it suggested was mistaken, and we have to find a new puzzle or a new way of putting the pieces together. Then we experiment with a new shape and apply the second- and third-level questions again. This way, through trial and error, we have a chance of finding the answer we want. When our questions on all three levels are well formulated, they help us recognize the solution to our problem even though we originally had only a vague notion of what it might be.

But if the questions are wrongly formulated, they can easily lead us astray. The original narrowing- down might narrow down on the wrong spot, focusing our attention away from the actual answer. The tests we set for our answers, and our standards for judging the results of those tests, might be misguided or aim too low.

So when you try to find an answer to a question of this sort, you have to do more than simply provide a piece that fits into the puzzle you’ve posed. You have to question the question, remembering that your answer will have an impact, in terms either of what the questioner—you or your listener— will do with it or of what it will do to the questioner.

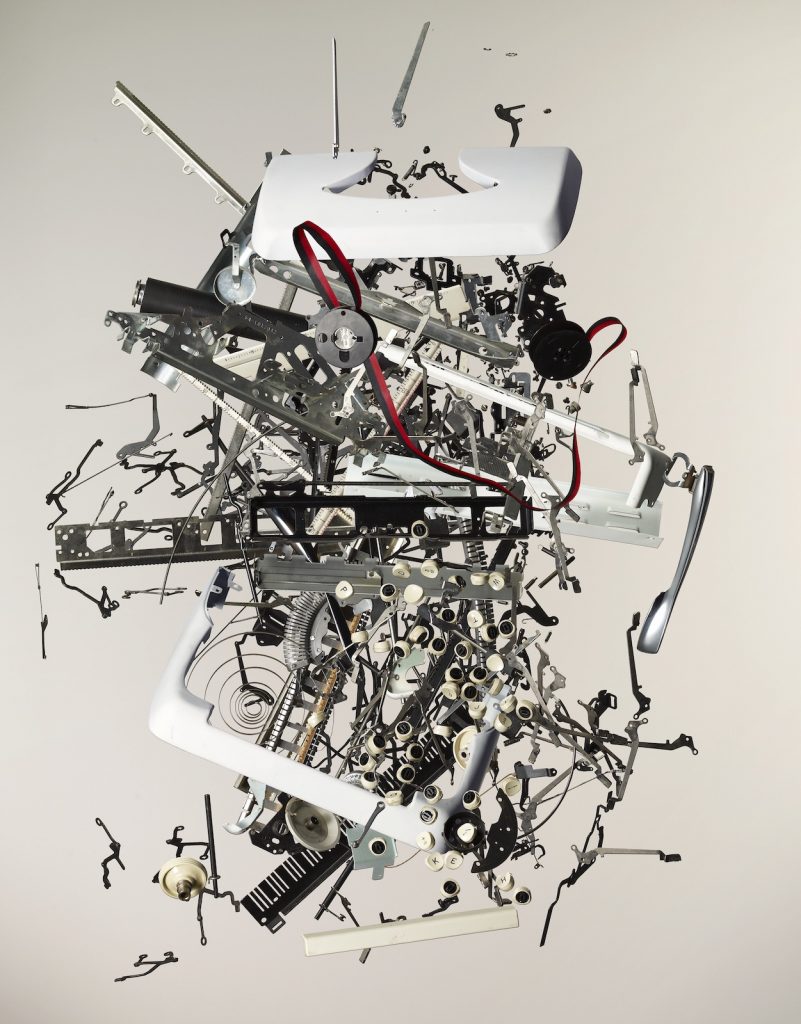

This means that the puzzle analogy, which is essentially static, has to be replaced with a more dynamic one. The questioner is assembling a complex tool or instrument, such as a piano or a machine, and—seeing that you have practical experience with what he wants to assemble—has asked you for a missing part and advice on how to use the completed instrument. In this case, the first-level questions would cover the structure of the instrument; the second-level questions would address the way it should be played or used; and the third-level questions would concern standards for determining whether it’s being played or used well. If you want to give responsible answers in a situation like this, you can’t simply supply the missing part. You first have to ascertain the desire behind the request: Does the questioner really want the part, or is he trying to make you look like a fool? Or does he want to use the part to assemble something more sinister? Even if his desire for the part is sincere, you want to make sure he’s planning to use the instrument for a beneficial purpose, that the instrument is the correct one for the purpose he has in mind, and that he knows how to use the instrument in a way that doesn’t cause inadvertent harm.

In other words, when you take into consideration the impact of the knowledge you’re providing, simply being truthful is not enough. You also have to ensure that your answer will be beneficial. If it’s challenging to your listener, you have to take care in presenting it with words that are timely, that is, appropriate to the situation and the listener’s level of skill and understanding.

This was the Buddha’s approach to the responsibilities he took on when answering questions. He had learned from experience that the act of framing skillful questions played an essential role in directing his own search for release, so his first step in helping his listeners overcome their ignorance was to show them how to give it the proper shape: how to frame the questions they addressed to him so that they would recognize the truth and utility of his solutions when they heard them. If a question was poorly worded, he would either reframe it before answering it, or put it aside, explaining why its underlying frame would block the path to the end of suffering.

However, he had also learned from personal experience the importance of self cross-examination in testing the original frames he had formulated and the answers he had come up within the course of his quest. Thus he also wanted to teach his listeners how to pose the questions they addressed to themselves, so that they could become independent in the dhamma and learn to overcome their ignorance on their own.

So if we want to understand the Buddha’s teachings and use them effectively for their intended purpose, we have to view them in terms of the questions they were and were not meant to answer. By watching the Buddha in action as he responds to the wide range of questions that people in his time brought to their practice, we can learn how to be more skillful and discerning—more effective—in the questions we bring to our own practice.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.