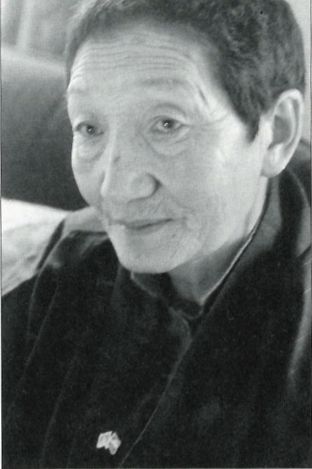

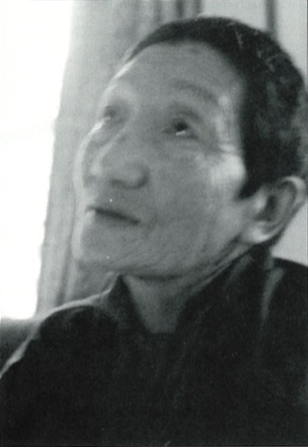

Ani Pachen was born in 1933, the daughter of a powerful local chieftain in the great, wild expanses of eastern Tibet. Soon after her twenty-first birthday, as the Chinese invasion thundered through her countryside, Pachen’s father died, leaving her in charge of her family and the freedom fighters he commanded. Overnight, she became one of the few female leaders of the resistance movement until she, her family, and hundreds of her kinsmen and neighbors were finally captured and imprisoned. For more than twenty years she endured relentless torture, enforced labor, and near starvation in Chinese work camps. But Pachen’s legacy of grit and defiance, as well as her single-minded devotion to the Buddha’s teachings, helped her survive, and, ultimately, to escape to India, where she ordained as a nun and met His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Sorrow Mountain: The Journey of a Tibetan Warrior Nun, written with Adelaide Donnelley, is the simply told story of Ani Pachen’s extraordinary life, and shows, using the ordinary details of life, how the Chinese government has tried and failed to destroy the heart of Tibet. She speaks with Tricycle:

In Sorrow Mountain, you talk about how stubborn and defiant you were as a young woman and how you battled those aspects of ego. Did those same characteristics help you survive all those years of torture in Chinese prisons?

I was too headstrong and independent when I was young. I had everything I wanted, so I had no understanding of suffering, only a religious understanding—that when we’re born, we’re born into suffering. I don’t think that was a good quality, or that it helped me. It was my karma. Being tortured, during the struggle sessions [brutal interrogations], I came to understand suffering personally.

You describe how envisioning the Dalai Lama, and the hope of meeting him, kept you afloat. Now he’s someone you know rather well. What is that like?

I think I did something really good in a previous life to be this fortunate. Thousands of Tibetans who had him in their hearts and minds every day died in prison without ever getting to see him. I get to see him every month, whether it’s in a close audience, or from far away. It’s unbelievable.

After your release from prison, you did chod practice in a charnel ground. [Chod is a practice where one offers one’s body to demons as a way to destroy the ego.] You said that that practice changed your experience of fear forever.

I still felt a lot of fear, especially when I was escaping from Tibet to India. I am afraid of things like being robbed or attacked. But when I was young, I had so much fear of spirits and wild animals. Amdo Jetsun [an elderly woman sage who was Ani Pachen’s teacher after prison] showed me how your mind creates that. Now, I don’t have that kind of fear of the unknown.

What about anger?

When I was in prison, I had such strong anger and hatred against the Chinese. I saw what they did—how they tried to destroy our culture and totally eliminate our race. That was their plan. After I was released, I got active in politics, in the demonstrations in Lhasa, and my anger kept going. Then I got to Dharamsala. The pace was slower, I got the teachings from His Holiness, and was able to remember the teachings from my own lama, Gyalsay Rinpoche. I became a nun. I calmed down. Now I don’t feel anger against individual Chinese. And I see that it’s not just us—the Chinese, the Mongolians, they are suffering, too.

For Westerners, your descriptions of growing up as a tribal princess, always on horseback, sound so wonderful and exotic. What are your favorite memories of those days?

The very best times were when my whole family would go together in the summer to the nomad camps. We’d camp by the river. The grasses and flowers were as tall as I was. We’d weave flower hats for our heads and eat as much cheese as we wanted. My other favorite times were during Losar [Tibetan New Year]. Usually, my father would take his meals in his own room, with his ministers. But on the holiday, he and the whole family would eat together. That was my favorite part of the year. Sometimes I miss it so much. But whenever I hear a teaching on impermanence, it helps me. Nothing is permanent—not wealth, not people, not even your body. That understanding really calms me down.

What do you make of your visit to the United States?

I think Americans are very fortunate. They have good karma. There’s equality here, freedom, good food—you can eat whatever you want if you have money. And there’s good consciousness about the environment. But I feel sorry for the old people here because there’s no dharma. That’s very sad, to come to the end of your life without the dharma.

—Mary Talbot

In 1959, Ani Pachen, her family and kinsmen are fleeing the Chinese forces about to descend on their village in Kham, eastern Tibet. They hope to reach Lhasa, hundreds of miles to the west, and find protection under the aegis of the Dalai Lama. They don’t know that the Chinese have already taken the capital and that His Holiness has escaped to India.

I rose early. The first rays of sun had just touched the peaks of the surrounding mountains. Farther up the valley, I could see the tents of the Derge division, and to the side of them, those from Lingkha Shipa.

In our part of the encampment, most of the people were still asleep, but smoke rising from a nearby tent was a sign that afew were up and beginning to make tea. Partly asleep, I slipped out of our tent, careful not to wake Mama, Granny, Kunsang, or Ani Rigzin. I crept toward the neighboring fire with a cup in my hand.

The sound of a cannon shattered the silence. A group of Chinese soldiers ran toward us, shouting and shooting their machine guns. Columns of dirt rose in the air, bullets falling like hail. Everywhere people started shouting. “Get up!” “Control the horses!” Everywhere there was confusion, frantic screams, whinnying horses, bleating yaks.

A young boy ran by me crying for his mother, his eyes wild. A moment later he fell to the ground, his shoulder ripped open. A horse broke loose just in front of me. It reared up and was shot in the neck. Cries came from every direction, everywhere people struggled to flee. Some leaped on horses without saddles, some ran by without boots.

Mama! Granny! I ran toward the tent. “Kunsang!” I screamed. “Help Granny . . . Mama . . . Ani Rigzin.” I ran toward the horses. The belt from my chupa came untied and dragged on the ground. I tripped as I ran.

The horses were reeling, rearing up, tearing the ropes trying to break loose. I grabbed for my horse’s halter. Crack! My hat flew off my head and landed on the ground. Om Mani Peme Hum, blessed Dorjee Phurba protect us. I snatched the hat and with horses in hand, raced back to our tent.

Kunsang pulled Granny up from her bedding and stood at her side, holding her arm. The old woman was having trouble standing, her eyes wide with fright.

With no time to saddle Shindruk, I picked up Granny and lifted her onto his bare back. I jumped on behind, laid my body over hers, and motioned the others to follow.

I pushed Shindruk in the direction of the hills. Others fled in the same direction; in the confusion one collided with us. I focused my eyes on the hill ahead and urged Shindruk forward. He shied several times, almost knocking us off. We rode past a dead horse and a man whose face was half off. Another, whose foot was gone. And others . . . too many. . . .

Sorrow Mountain, by Ani Pachen & Adelaide Donnelley, was published by Kodansha International in March 2000.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.