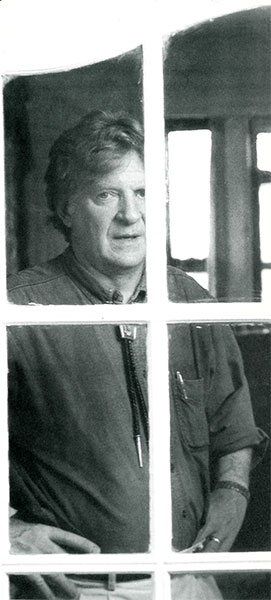

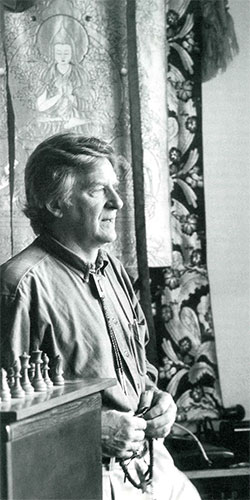

Robert A. F. Thurman is the Jey Tsong Khapa Professor of Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Studies at Columbia University. A former Tibetan Buddhist monk—the first Westerner ever to be so ordained—he is the cofounder and current director of Tibet House in New York City. For decades he has been a close friend of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and a prominent champion of Tibetan Buddhism and the Tibetan cause. He has translated classic texts from Tibetan to English and is the author of numerous books, most recentlyCircling the Sacred Mountain (Bantam, 1999) and Inner Revolution (Penguin, 1999). This interview was conducted at his office at Columbia University.

This past summer the Dalai Lama appeared in Central Park in New York City. Fifty thousand people were there. It was a watershed event for Buddhism in America. But when the Pope came toNew York he drew a crowd of one million. So how isBuddhism really doing in America?

I think Buddhism is doing pretty well here, although my theory is that Buddhism does best in America when it doesn’t bother to be Buddhism. I don’t agree that Buddhism is going to become a huge religious movement here. I follow the Dalai Lama, who, even though he had fifty thousand people, tells them, “I don’t want you to be Buddhist, necessarily. It’s better if you learn from Buddhism and then keep connected to the religions of your family, of your community, and develop the positive qualities that Buddhism would like you to develop within those settings.” He says that constantly, even when he is among Buddhists. It goes right along with his appeal to other religious leaders, to please stop converting members of other faiths, because we cannot afford a new era of inter-religious competition for market share.

What role will Buddhism play in America in the next century, if conversion is not the aim?

Where I see Buddhism contributing is in helping the Euro-American tradition, which is too outer-materiality oriented. We’ve had a strong focus on materialism since the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, which has resulted in our having tremendous power over physical nature, which gives us a great opportunity to destroy ourselves. We now need to balance that with knowledge of our mind and how it works. Here at the university, a religion major will take ten or twelve courses, but there’s no course that requires them to do a lab unit of meditating with, say, Jon Kabat-Zinn [author of Wherever You, Go, There You Are] to learn how to withdraw from impulsive violent emotions. Of course that could never be offered as Buddhism because then the Jews and the Christians and the Muslims and the Hindus would be upset—even other kinds of Buddhists would be upset. It could be given only as a kind of physical and mental self-discipline.

What you‘re talking about sounds like a distillation of Buddhism that can be swallowed by Americans.But is it a distillation or is it a denaturing? You‘re a proponent of an ancient and ornate way of life,Tibetan Buddhism. The Dalai Lama comes from that tradition, yet he presents a very simple message to Americans—basically, don’t worry, be happy, be kind. What about all the rest of Tibetan Buddhism? Is it not useful?

I’m delighted if someone is a Buddhist but I’m against saying, as a solution to anything, “Be a Buddhist.” It’s not that we’re denaturing in the sense that we’re pretending there is no Buddhism. We’re saying, “Take as much as you can. It is not the denominational change that is key, it’s the using of the discipline.”

This is fundamentally a Christian nation. How do you approach a Christian who says to you, ‘Jesus is theonly true way to salvation“?

I follow the Dalai Lama in saying, “You have every right to say that but if you really want to honor Jesus’ way, you should be able to say, ‘Jesus is the way for me,’ and you should be able to restrain yourself from saying that Jesus is the way for you or you or you.”

If you think the best way for Buddhism to help America is not explicitly as Buddhism, then what is thepoint of being Buddhist?

There is no point in being Buddhist! One does it for the sheer joy of swimming in the infinite!

Behind what you’re saying lie the basic Buddhist beliefs of interdependency and relative truth. I don’t think that’s going to wash very well with Christians, who have a very different belief—in God the Absolute. It’s always seemed to me that the conceptual divide between emptiness and God the Absolute is the final gulf between Buddhism and Christianity.

I don’t quite agree with that. I don’t think there is a final gulf. I would point to the Meister Eckhart approach to God, or the approach of St. John of the Cross, of those who see the desert at the heart of God, who sense the inconceivability of God, and who see at the heart of that a voidness, an openness, rather than some sort of dogma they can cling to and therefore feel they have hold of an absolute.

I wonder if the concept of emptiness, finally, is something that most people will shy away from because it’s too difficult. It’s so much easier to believe in a Father God, or in the Dalai Lama, or in the Pure Land—in these objects, these things.

Nagarjuna wrote that the Buddha was a little leery of teaching emptiness to anybody because they so easily misunderstood emptiness—that it was like a poison snake mis-grasped, that is could rip around and bite you. In those more traditional societies people had a more naïve, easier understanding. They just believe in Buddha, and in virtue, and it was fine. Going into shunyata[emptiness], you skirt the abyss of nihilism. But I argue that today we have already been bitten by the snake of nihilism, even if we call ourselves Christian. How many Christians do you know who, except during the last few weeks in a terminal ward, really live for the future life? And most Buddhists in Japan, for example, reject the idea of future life as some primitive myth. So we’re all bitten by the snake of nihilism, from that point of view.

Which presents an opportunity.

It presents a necessity that emptiness not be made that difficult. Some of our operative psychologies are based on an insight into emptiness. Much of trans-personal work is based on it, in seeing that the strong ego is not the rigid one but the flexible one that is permeable in its boundaries. That, in a way, is an understanding of emptiness. We don’t have to make emptiness some lofty thing that’s far away; it isn’t, actually. Take the deconstructing of sexism. To overcome the idea that I’m a male or female—that there’s a real maleness about me or a real femaleness about me—and to realize that actually I could be male or female, and that I have male and female elements in me, and that therefore there’s no reason to despise the other as male or female or as different from me—that involves some understanding of emptiness. But this is not taught as psychology. Daniel Goleman’s concept of emotional intelligence is actually the dharma. If he had said, “This is a Buddhist theory I’m giving you,” it wouldn’t have gotten on Oprah. Dan’s book [Emotional Intelligence] is Buddhism offering a tremendous service to the American people by not insisting on presenting itself as Buddhism.

That‘s an excellent example of Buddhism influencing American life. Flip over the coin. How is America affecting Buddhism?

In America, people are on deep existential quests. Life is deranged by technology and industry and broken families and the whole dislocation and chaos of modernity. Therefore, people are approaching Buddhism as if it was primary reality investigation, the way it was originally approached. People worry, “Gee, will American Buddhism denature everything and dilute it?” And some people even want to come on with a big fancy Zen robe or they want to have a title, or to wear a big Tibetan hat and act like a lama. But in fact the potential greatness of American Buddhism is that people need to understand themselves and their world, and that’s what they want from these methods. And when they get that understanding they will use it to help others, without demanding that it all become Buddhist.

What do you think the role of monasticism is and will be in America? Is there a point to being a monk inAmerican Buddhism if America is better served by Buddhism manifesting in a more secular way?

America must stay religiously pluralistic and Buddhism is rightfully part of that patchwork quilt. Though I’m no longer a monk, I revere those who manage to thrive as nuns and monks, and I try to contribute to their support. I think they’re the Special Forces of Buddhist practice. I think also they could be good nuns and monks yet serve effectively in secular ways, as doctors, therapists, teachers, nurses, writers, artists, social workers.

We’ve been talking about how Buddhism might manifest within the plurality of American culture. What about the plurality within Buddhism itself? Different strains of Buddhism are coming to this country, and while there is cooperation, there is also head-butting. One of the most interesting head–butts was betweenyou and Stephen Batchelor [author of Buddhism Without Beliefs], regarding the need for traditional beliefs such as in reincarnation.

I think one of the strengths of this renaissance of American Buddhism is the various traditions working together and not operating in the cultural isolation in which they operated in Asia, where they became localized and nationalized. We can get back to the original pluralism of Indian Buddhism. Once Dick Baker [Richard Baker, former abbot of San Francisco Zen Center] and I worked together on a Buddhist university that would be a truly American Buddhist university in that it wouldn’t belong to any particular Asian Buddhist order. That, to me, is really necessary, and that’s where I think the Buddhist educational effort can be magnified enormously.

Well, what is the point of holding onto a belief in, say, reincarnation? Do you believe it because it‘s trueor because it’s efficacious?

Both. Because when you say “true,” what kind of truth? Technically, in Buddhism, reincarnation is not absolutely true, but neither is non-reincarnation. But within the teachings on the relative, the teaching about cause and effect—karma—is the most sacred cow there is. Because if you think that what you do has no consequence, if you carry an image of radical discontinuity at physical death, then that is totally inefficacious for your spiritual growth. Efficacy is, in fact, one of the major guarantors of relative truth—and being relatively true is being true enough.

I think what bothers some people is when they’re offered what seem to be simplistic interpretations ofreincarnation. People recently named Richard Gere the sexiest man alive. Did he have an upstandingseries of previous lives, that he turned out so sexy in this incarnation?

How else did it happen? That he was rewarded by God? Or he was rewarded by his parents? What else are you going to say?

Luck of the draw.

The problem with luck of the draw is that it’s debilitating, because then you have no stake in working for the future. Your generosity has no output, your self-restraint has no fruition. When the pressure is on, are you going to be a good guy or are you going to indulge your greed or your hatred? Milarepa used to say, “Thank goodness I was awakened about my having killed those thirty-five people, and I truly became afraid of hell, because otherwise I never would have made what I’ve made.”

How does reincarnation bear upon someone being born poor and into a despised class—say, as poor black or Native American—in white America?

Reincarnation means that everyone has at some time or another been born in every conceivable species, race, gender, or class. So rigid barriers such as overt caste systems or racist, sexist, or classist ideologies and social practices tend to be eroded through the wide acceptance of karmic biology. And by believing in reincarnation, individuals who suffer from being stigmatized can feel they have some power over their fate, confident that no effort will be wasted. Of course, the danger of karmic biological common sense is that those dominant in a culture can use the karmic explanation to blame those less dominant. But this danger also exists in doctrines of materialistic genetic determinism, will-of-God fatalism, and so on. And karmically inclined Buddhists can control their own selfishness through compassion, altruism, and wisdom of interconnectedness.

What does this mean regarding America‘s Horatio Alger, pull-yourself–up-by–your-bootstraps mentality?

Horation Alger would have had an immensely long bootstrap to pull on if he’d lived in a universe where positive development toward Buddhahood could continue indefinitely for life after life. Buddhahood in an over-the-top ideal for good old American know-how and do-how, and perhaps for new American be-how!

Do you really believe that people come to goodness through the weilding of a stick?

Who can deny that caution—fear of unpleasant consequences—often compels us to restrain negative actions?

Of course they do, but doesn’t goodness become its own reward? Not beccause you’re concerned about far-future karmic consequences but because something in you grows and you sense the rightness of it?

Certainly. Caution leads to restraint of the negative, but then, once we’ve turned around, we go on to greater good out of sheer joy. Take this piece of chocolate cake, my favorite. I often gorge on it. But I’ve learned it makes me tired later. I gain useless ounces. I’ll ruin my health. Once I’m eating better, I learn to cok delicious organic dishes, enjoying every healthy bite and sharing it with guests. Mindfulness in ethics translates as prudence, boring as it may seem. We go on to compassion and transcendent deeds.

I have some questions about the Dalai Lama. The first is a Barbara Walters type of question: Most of us know His Holiness only through his public appearances. Yet you know him as a friend. What is the private Dalai Lama really like?

He’s a nice guy, he’s got a good sense of humor. Nowadays, frankly, he’s a little stressed out. After the eighties there was a little bit of a relaxation, there was some hope that Deng Xiaoping would come to his senses in his old age. Tiananmen Square was the definitive signal that he was just as insane as Mao was, and then he picked successors who are even more nasty than him. So in the nineties, after all the effort and the Nobel Peace Prize and world consciousness being raised, there are more repressive policies than ever in Tibet. It’s heart-wrenching. His Holiness remains in good humor and he doesn’t get bitter, but it’s the darkest moment before the dawn, and my heart goes out to him.

Your own relationship with His Holiness…

I love the guy, and I learn a lot from him. When we were both in our twenties, we were more friends and fellow students, though on the ethical level he ordained me as a full monk. His senior tutor was my main guru, after Geshe Wangyal. Since 1980 I received invitations from him and began to envision him as my main guru. In the context of our work for the cause of Tibet, I have to think for myself, take responsibility for contributing as an American professor, on my own.

For a lot of Americans “guru” is a loaded term. I should think especially for someone in academia it’s troubling, because some might say, “Bob Thurman isn’t completely free to have his own thoughts because he has a guru.”

This is one area where I think Tibet needs to be reformed, and the Dalai Lama, I would say, agrees, although it’s not been much on his agenda. In on of the Western teachers’ meetings, somebody was telling him about the misbehavior of some Tibetans. And somebody mentioned the infallibility of the lama. The Dalai Lama shook his head and said, “You know, that doctrine, it’s poison.” People were shocked. But while it can be poison, the guru relationship is a central element of Tibetan Buddhism, the lama transference in initiatory contexts. What’s poison is that it so easily becomes corrupted, spoiling other elements of the relationship. This has not been well addressed. When His Holiness gives an initiation, you have to visualize him as Buddha, with no flaws. But when you’re driving him in a car, he does not want you to think of him as Buddha, he wants you to think of him as a fragile human being who could be hurt if you make the wrong turn.

We spoke earlier of deconstructing sexism, so I want to ask you about the Dalai Lama and his teaching that some orifices are proper channels for sex and some are not. A lot of people love the Dalai Lama, but they look at Tibetan Buddhism and think it’shomophobic—and also sexist, in that most of the teachers are male.

I think they’re right. The Dalai Lama himself doesn’t really know about sexual problems. He doesn’t really know about the married life. His original position on homosexuality, given in the Outmagazine interview, was total tolerance, as long as it is consensual, and no one is hurt. He gets more worried about monastics, about keeping monasticism alive. The Tibetan weakness on female monasticism, however, is not as great as in the Theravadin countries where they no longer have any nuns at all. Tibetan Buddhism is not as chauvinist as other forms in Asia, but it’s still bad in this area, and the Dalai Lama is implementing reforms to better the status of nuns. As for the “wrong orifices” quote, His Holiness read that traditional text in the context of teaching would-be monks not to break their vows. Even auto-eroticism is forbidden for monastics. Later, after there was a lot of confusion about his position on gay and lesbian sexuality, I tried to joke about it: “But more homosexuality among laypeople is good for population control, don’t you think?” It fell flat.

You exhibit such confidence when you talk about all this. What isthe source of your confidence and your faith?

The source of my faith that reason will prevail about Tibet is intellectual, I have to admit. Emotionally, maybe I speak confidently because I’m trying to persuade myself. Emotionally, I’m a chicken. It’s all going to go wrong, somebody’s going to arrest me. But His Holiness, I feel, remains optimistic in spite of the very, very darkness of the current moment, because it is our duty to be optimistic. If the world blows up, as the blinding nuclear flash is searing us into skeletons we will be in a state of disbelief. But we will not feel the regret that we in any way lent to this event by thinking, “Oh, it will all go wrong so I won’t try that hard.” I think that we at the turn of the twenty-first century have a duty to visualize a positive outcome, not because in some New Age way visualizing it will make it happen, but because visualizing it will make us work for it to happen.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.