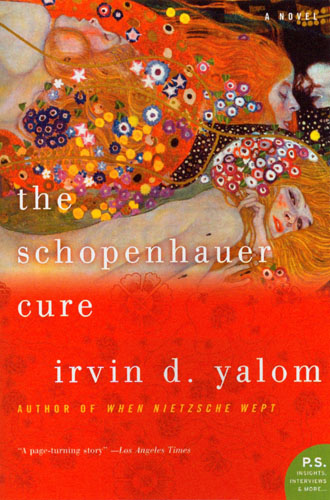

The Schopenhauer Cure

Irvin D. Yalom

New York: Harper Perennial, January 2006

384 pp.; $13.95 (paper)

“Nice things are nicer than nasty ones.” his perfectly constructed sentence, from the 1954 Kingsley Amis novel Lucky Jim, wittily expresses one of the more important sentiments in twentieth-century English literature. But it is perhaps a sentence in both senses of the word; and The Schopenhauer Cure, Irvin Yalom’s latest novel, is an extended meditation on the problems it presents, providing both a challenge to our dharmic slumbers and an excellent introduction to the work of Arthur Schopenhauer, a German philosopher who embraced Hindu and Buddhist ideas long before Nietzsche and Heidegger hinted at a similar rapprochement.

Why is Schopenhauer important? I can put it no more succinctly than does Stephen Batchelor, in his book The Awakening of the West: “Schopenhauer believed that by completing the revolutionary work of Kant, his system was the culmination of the Western philosophical tradition that began with Descartes. He was convinced that critical thinking had led him to the same conclusions that centuries before, Indian and Buddhist teachers had intuited through allegory and mystical insight.” Schopenhauer believed that Western philosophy could prove to us that our senses give us access only to a dreamlike world of illusion and that the filters that we use to interpret this dream (time, space, causality) are not “out there” in the world but in our minds. No one will pretend that his work is easy to understand, for he assumes that we have not only read and digested Kant, but that we are also willing to grapple with crucial differences between the first and second editions of the Critique of Pure Reason. And Schopenhauer is reader-hostile in other ways, too: his superiority complex was legendary, and he delighted in referring to his fellow human beings as “bipeds.”

Irvin Yalom is an existential psychotherapist (author of Love’s Executioner, a marvelous collection of true stories from the therapist’s office) who has turned to fiction in recent years, most notably with When Nietzsche Wept. Not as explicitly Buddhist as Mark Epstein, nor as implicitly so as Adam Phillips, Yalom is centered on the notion that most of our neuroses are excuses for ducking the great matter of death. His stories (fictional and otherwise) are nearly always about psychotherapists, and The Schopenhauer Cure is no exception. It concerns Julius Hertzfeld, a therapist who learns that he has terminal cancer. This becomes the opportunity for him to feel “a flood of compassion . . . for all his fellow humans who are victims of that freakish twist of evolution that grants self-awareness but not the requisite psychological equipment to deal with the pain of transient existence.” Seeking consolation in his work, Hertzfeld decides to contact Philip Slate, an ex-patient who, it turns out, has become a “philosophical counselor” following his own recovery from sex addiction via his reading of Schopenhauer.

It is a fabulous but convincing premise, and Yalom laces the tale with chapters that recount the life of Schopenhauer and the development of his thought, from his stark upbringing with its dark lack of maternal love to the happy coda, wherein for a few years he enjoyed a bout of fame followed by a sudden and apparently painless death. Some of the best writing in the book comes in these sections, and the intermingling of the factual and the fictional is neatly done.

The remainder of the action occurs mostly in an encounter group, none of whose members seemed at all real to this reviewer. One is Pam, a college lecturer who attends meditation retreats, including a trip to India to sit with SN Goenka, described in scenes so thinly written that they leave one wondering why people have been doing this kind of thing for thousands of years. Even less appealing is the characterization of Tony, the one blue-collar member of the group, whose redemption via the plot cannot make up for the fact that he is mostly noticed for his apparent inability to understand any word that is not monosyllabic. I don’t know what Tony is doing in this book, but Pam is clearly present to give Julius/Yalom a chance to critique the dharma, and the end result is unsatisfying, because the narration never really engages that world with the kind of commitment that is reserved for Schopenhauer and Freud.

Yalom has Julius musing on detachment (“the Buddha’s truth”) thus: “Too much of life’s show is missed if we never take off our coats and join in on the fun. Why rush to the exit door before closing time?” He wants Julius to show us that nice things are, in the end, nicer than nasty ones. But Philip has other ideas, for he has found salvation in Schopenhauer and has discovered there the very same path that is found in Buddhist practice—the effort to negate or at least expose egoism and thus suspend the will. This is the component of Schopenhauer that provides an original piece to the Kantian story, because it was his insight that Kant’s world of things-in-themselves beyond the mind could be found via the senses, if we looked at the relationship between our bodies and our will. Schopenhauer is marked by his time, and his comments on women can be read only if one holds one’s nose, with the page at some distance, but his philosophical thoughts were prescient.

Schopenhauer introduced the now-fashionable emphasis on the human body into Western thinking, in a new and startling manner, via the Kantian distinction between the world as perceived by human beings and things-in-themselves. Most people have little or no interest in philosophy precisely because this kind of thinking seems to create very difficult ways of understanding the world that appear to be of no use to us; hence the philosophy shelves of our bookstores are increasingly overrun by self-help books, or books about Buddhism and “spirituality,” whose grasp of reality may be tenuous or hopelessly out of date but whose volumes at least give us something to do. Yet Kant’s point is terribly important, for he has shown us that our everyday sense perceptions are, just as the dharma insists, an accidental matter of biology, not a God-given tool kit for decoding this mysterious place we call the world. This deeply nontheistic take on Kant was developed by Schopenhauer, who argued that appearance and reality are linked, since our bodies exist in the world (and are things-in-themselves) but are accessed directly through our consciousness, via the will.

The bad news (and with Schopenhauer the tidings are rarely sunny) is that this body insists on reproducing itself at all costs, so that we are enslaved to corporeal urges that cannot make us happy. Sound familiar? We should, in the end, have sympathy for Schopenhauer. He was unable to see, as Wittgenstein (and for that matter, T. S. Eliot) did after climbing onto his shoulders, that while the truths of religion are the truths of fellow sufferers, humanly constructed most surely, that does not mean that they are necessarily the dreams of deluded bipeds. What Yalom seems to want to do, like Kingsley Amis before him, is present us with the Four Ignoble Half-Truths as a way out of the human dilemma: (1) Life is joyful, (2) The cause of joy is appetite, (3) The way to fulfill appetite is to feed it, (4) An eightfold trough is available for this feeding frenzy, enabling us to satisfy our lust for sex, food, love, intoxication, companionship, amusement, power . . . and of course not forgetting—spiritual attainment.

In the end, however, these half-truths produce their own narrative karma, which comes in the shape of three holes in the story. First, The Schopenhauer Cure lacks a credible account of what it is like to meditate, to sit, to be with one’s being in a nondualistic manner. Second, the pain of Julius Hertzfeld’s illness serves here only as a plot premise and not, oddly enough, as an opportunity to explore physical and mental suffering. And third, we find a surprising gap at the story’s conclusion, where Julius’s ending happens offstage—a curious way to tackle mortality in a book about philosophy and meditation. Irvin Yalom is now in his seventies, and we can surely understand why he would want to present us with a vibrant manifesto for those of us who are still above ground, a therapist’s treatise on the importance of living fully in the sensual world. This he does with some success. But a bigger book, one that took Schopenhauer and the dharma more seriously, would also encompass the other side of life’s narrative, where the stillness and the sickness and the dying are also a big part of the story.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.