Jiddu Krishnamurti mistrusted all religions and denounced the Eastern convention of deifying living spiritual masters. But by the time he died in Ojai, California, in 1986 at the age of 91, he had helped—perhaps more than anyone in this century—to introduce Eastern teachings on the nature of mind to the West.

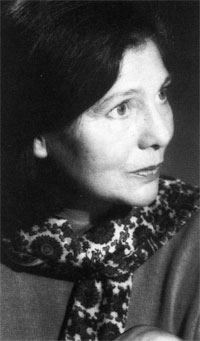

In Lives in the Shadow with J. Krishnamurti (London: Bloomsbury Press, 1991), the prime subjects diminished by this mythic figure are the author’s parents, the American-born Rosalind and Rajagopal, Krishnamurti’s compatriot and dedicated associate; but the most compelling character is the shadow side of Krishnamurti himself. While Radha Rajagopal Sloss raises disquieting questions, her book remains a refreshing alternative to the many hagiographic portraits proffered by Krishnamurti’s devotees.

With delicacy, detail, and at times a painstaking attention to fair play, Radha Sloss addresses the confusion that arises when spiritual insight is presented and/or perceived in contradiction with daily life. Radha Sloss’s mother was Krishnamurti’s clandestine lover for some twenty-five years, and the slow dissolution of that romance was followed by a series of bitter legal battles over money and property initiated by the Krishnamurti Foundation and directed against Radha Sloss’s father, Rajagopal.

After administering to Krishnamurti’s needs for over forty years as well as overseeing the editing and publication of his work, Rajagopal was shunned by the inner circle and accused by Krishnamurti of mismanaging money. Krishnamurti’s rejection of Rajagopal was taken at face value by his close supporters, but the author convincingly portrays her father as the victim of a personal vendetta fueled by passions of the heart.

While retaining much of her childhood affection for Krishnamurti, who was a more active parent than her biological father, the most poignant anguish in Lives in the Shadow with Krishnamurti pervades the author’s defense of her father. Yet the major drama of Krishnamurti’s life was played out long before Radha Rajagopal Sloss was born.

At age eight, Krishnamurti, a frail and dreamy child, lice-ridden and open-mouthed, was discovered on a beach in South India and proclaimed by leaders of the Theosophical Society to be the next World Teacher. With exacting expectations, the Theosophists initiated the “coming messiah” into the spirit worlds with which they claimed to have direct contact. In addition, they introduced him to the mannered informalities of international society. But at the age of twenty-nine, Krishnamurti rebelled.

Refusing the role of the chosen one, he claimed that truth could not be approached by way of a teacher and that enlightenment rendered all belief systems equally and inherently useless. Helping others find their way in a pathless land became Krishnamurti’s avowed mission for the next seven decades.

During that time, he communicated his message in riveting language and provoked inquiries into human nature and the mind that were so fresh and compelling that his enlightenment and authenticity were affirmed for hundreds of thousands of people around the world. His books are printed in over forty languages, and of the fifty titles available in English, over thirty-five have sold more than 100,000 copies each. Yet, in a scenario that has become all too familiar to American Buddhist communities, Radha Rajagopal Sloss leaves us struggling to come to terms with the lives of our spiritual guides, and struggling as well with our personal investment in both the creation and destruction of their mythic dimensions.

The Interview

This interview was conducted for Tricycle by Helen Tworkov.

Tricycle: Some people have said that your portrait of a twenty-five-year love affair between your mother and Krishnamurti—including three aborted pregnancies—cannot be substantiated, that you have no proof and that no one can corroborate your story.

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: I was an eyewitness. When I started this book, I had planned to publish letters from Krishna to my mother, which I have and which corroborate what I say. But as you may know, the copyright laws have been changed. Published letters now need the consent of the sender or of that person’s literary estate. I was not able to obtain permission to publish the letters; even if I donate them to a library, they will be available for research but not for publication.

Tricycle: I first heard about your manuscript from an editor at Knopf who found the story implausible, convinced that Krishnamurti’s celibacy was beyond doubt. I then mentioned the manuscript to a very rational philosophy professor, who said, “I have met Krishnamurti. I can assure you that this story cannot be true.” Is this typical of the kind of response you have received?

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: Thus far I have only heard from people who wanted to thank me for affirming things about Krishnamurti that they had suspected all along. I have heard second- and third-hand about people who don’t believe me or were offended that I shattered the myth, but the people that I know to be critical will not read the book. They don’t want to.

Tricycle: They don’t want the myth destroyed?

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: It is too important to them.

Tricycle: What is happening with the American publication of your book?

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: Bloomsbury, the English press, was in negotiation with a press in the United States that had considered publishing it there, but apparently someone told them that the book was heavily biased and they decided not to publish it after all. I am sure there is more to it, but I don’t know what.

Tricycle: Your book raises issues parallel to those of American Buddhists, such as the need to question authority. Of course, this comes after a few decades in which we actively helped build the very pedestals that we are now trying to bring down.

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: That’s part of the story. When Krishna was at his best, in my opinion, he did not want followers. He warned people, “Do not follow an authority. Do not follow me.”

Tricycle: One of the many ironies about Krishnamurti is that this very rejection defined him as authentic and utterly trustworthy.

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: Well, that was when he was very young. You know he grew up in India, where there were wonderful sages who lived very simple lives and did not need fancy clothes, first-class airfares, cars, and all that. At some point, Krishna did want that. He was not willing to give that up. Therefore, he couldn’t turn away followers. Or supporters. He had to have people with lots of money to support him, his travels, his entourage, his schools. And those people needed to believe deeply in his image.

Tricycle: Did your father believe in this image?

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: My father felt that the words that Krishna spoke were very important, not his image. He made this distinction.

Tricycle: It seemed that your father was caught in the same dilemma as many others. Having invested so much of his own life in Krishnamurti, he felt that by protecting Krishnamurti he was protecting himself as well.

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: I can’t totally explain my father; I think I see Krishna more clearly. My father told me that even before I was born he began to see that, indeed, there was no World Teacher here, but that by some strange miracle Krishna said things that were very good. And then my father felt that no matter what his personal feelings were, he had made a commitment to look after Krishnamurti. He still retained certain aspects of his Hindu background. His commitment was to a purpose greater than either himself or Krishna. He looked after him in a very personal way, that is, in terms of his physical health, shelter, food, money.

I don’t know what he thought about all the implications. He never discussed his private thoughts in those days. He just kept on doing his job, and then everything fell apart. The lawsuits started, and people turned on him. He realized that Krishna was behind all that, but by then, it was too late for him to walk away.

Tricycle: What was the intention behind the myth of celibacy?

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: I can only speculate, because this was never discussed. I may be mistaken, but a lot of his followers were wealthy men and women, but mostly women, with very strong emotional attachments to him. And they could tolerate the fact that he would never return their attachment as long as it was understood that he was not returning anyone’s. Krishnamurti was certainly capable of being aware of that situation. Whether or not he was, I don’t know. He was ambivalent about many things.

For years he had talked about real love being nonpossessive and nonattached to any individual, that the ultimate way to be was not to need a particular human being or a family, that one loved at large—so to speak. So at some point, it would have been a contradiction to admit that he had in fact been in love with one person for many years.

Tricycle: How could a love affair that lasted twenty-five years be kept a secret?

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: Look at the response from the editor and the philosopher. Look at the denial. But it wasn’t the affair that was so upsetting; it was all the lying.

Tricycle: That sounds familiar. Within the Buddhist communities that have lived through the exposure of clandestine sexual behavior on the part of a teacher, the feelings of betrayal tend to center on the duplicity and hypocrisy.

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: Baker Roshi telephoned the other day. He thought my book would contribute to the investigations of the teacher-student relationship in this country.

Tricycle: Well, he would know.

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: But see, the difference is that while Richard Baker was the roshi and abbot, head teacher and high priest of the Zen center in San Francisco, Krishnamurti would not even acknowledge that he was a teacher.

Tricycle: So that neither the assumed nor avowed ethics of a teacher pertained to him?

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: He didn’t like labels, so he refused to apply them to himself.

Tricycle: Your descriptions suggest that he was quite self-conscious about cultivating an image that assured a following.

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: This was the dichotomy in him. I once heard a Tibetan rinpoche talk about how careful a teacher has to be in taking on students. Once you took on a student you were totally responsible and committed for life to that student. Even if the student walks away from the teacher, the teacher is still committed.

To my knowledge, Krishna never established that sort of relationship with anyone. He was more like a stock advisor. “These are good stocks. They may go down, but I think they are good. Buy at your own risk.” He never wanted responsibility. He took responsibility for no one and for nothing. That sets him apart from other teachers, but it does not absolve him from the problem of lying and hypocrisy.

Tricycle: Does his lying and hypocrisy detract from his teachings?

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: I don’t feel that it invalidates a great deal of what he had to say. Because a person lies about certain things, it doesn’t mean that he doesn’t have truths to tell. It’s up to us to discern what to make of it for ourselves. In some ways, knowing this side of Krishnamurti—his relationship with my mother—gives a validity to certain things that wasn’t there before.

Tricycle: I wonder if the disciples of Krishnamurti would agree with you. After all, he didn’t just talk. He presented himself as a man who transcended, as he put it, “the repetition of memory.” He was, in theory, no longer enslaved by the habits of desire. He was living proof that this most difficult task was attainable. Did he ever promote celibacy?

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: I have been told recently by some individuals who had extensive interviews with him during the Forties that he strongly advocated celibacy for them, saying that sexuality could be hazardous to the very delicate process of enlightenment (perhaps he didn’t use that word). These people are now very upset to discover what was going on simultaneously in his personal life. They feel they were asked to build on a false premise. Later, he appears to have modified his position.

Tricycle: With regard to Krishnamurti’s sexual activities, you seem determined to be fair, prudent in your own judgements. But when it comes to Krishnamurti’s so-called enlightenment experiences, you sound quite cynical, determined to disbelieve. All the Krishnamurti biographies (Mary Lutyen’s, Pupul Jayakar’s, etc.) include well-documented descriptions of the “process”—physical seizures or fits accompanied by fevers and chills and headaches.

These episodes have been accepted by many people as authentic enlightenment experiences. And yet you suggest that these experiences might have been manipulations on Krishnamurti’s part to induce women to take care of him and that they are the result of unresolved infantile needs for his mother. You insist on reducing these episodes to solely psychological phenomena.

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: I don’t insist. It is just my way of seeing it. Everyone must choose his or her own explanation. From my experience and what I witnessed, this makes the most sense to me, that’s all. I may be a very skeptical person, but Krishna himself brought me up that way. Believing in other people’s “enlightenment” experiences was considered by him irrelevant. Therefore, even if his was genuine, by his own reasoning it should not be used to elevate his spiritual status.

Tricycle: It does seem that in deflating the myths about Krishnamurti you needed to invalidate the most tangible expressions of his enlightenment.

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: I don’t tend to think of some people as being superior to others. I think we all have different paths. And I try not to put a value on whether it is better to be a teacher of literature or a teacher of math or a spiritual teacher or an advisor in the stock market. These are just different courses one can take. I feel a little skeptical about so-called spiritually advanced or enlightened persons in general, or perhaps just cautious.

Tricycle: But Krishnamurti’s episodes are comparable to other well-documented experiences, for example, Irina Tweedie’s and Madame Blavatsky’s.

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: That’s very true. Madame Blavatsky’s descriptions were well documented, and Krishnamurti was brought up on these accounts. A lot of things can be simulated. I didn’t say that he did this consciously—well, I guess I am a bit of a skeptic.

Tricycle: And your mother?

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: My mother really has a different view of Krishnamurti. She sees a more complete split and believes one part did not know what the other was doing. Although she was only nineteen when she cared for him during the first episodes, she did have some questions. That one little scene where he is fondling her breasts in the middle of one of his seizures suggested to her that something was not quite cricket. And the timing, the way the seizures always occurred with women around—why didn’t they ever occur under different circumstances?

Tricycle: How much of writing this book was a personal exorcism for you?

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: Not as much as it might appear. You see, I never went through the shock process the way others did, because the things that I wrote about were a part of my life ever since I was an infant. It was the gradual unfolding of character that became more and more clear.

Tricycle: But you also wanted to defend your father.

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: If Krishnamurti turns out to be an important figure, a balanced record should exist. And yes, it is true, I do think that for my own sake, and for my father’s, I wanted things better explained than they have been in other chronicles. Then, too, the truth about a figure like this might create a better perspective for people who are seriously interested in his ideas.

Tricycle: You depict a charmed circle around Krishnamurti composed of international intellectuals and aristocrats who formed a kind of spiritual jet set. Could these people have learned anything from someone who looked, acted, dressed, talked, in a more ordinary way? Could they have paid attention to anyone who was a little less charismatic?

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: You mean to learn on a spiritual level?

Tricycle: Yes. In American Buddhist communities we have seen the misguided confusion of charisma with wisdom, time and again. In the case of Krishnamurti, everything about him, including his circle, became extra-ordinary.

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: Well, what did they actually learn? What depth of personal change did each person undergo? One cannot give a general answer. It is completely individual.

Tricycle: At the end of your story, there is disarray, disharmony, and confusion. Even at the beginning, in addition to the duplicity, which is very problematic, there are many instances in which Krishnamurti is portrayed as just not a very nice guy.

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: And then what went on around him was not very nice either.

Tricycle: So where does that leave us?

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: We have different ways of learning. My way is to see a person in action, in a specific situation. Life is a series of problems, and it is a matter, on a daily basis, of how we cope. Sometimes you come upon a person who copes extraordinarily well. Recently, there was a Tibetan rinpoche visiting us, and I watched him learn how to swim for the first time. He went to the far end of the pool and dove in.

Growing up with Krishna, I saw a lot of odd little things that he did in his daily life that taught me more than listening to his formal teaching, and I know at least three or four people who heard one sentence of Krishna’s and received it in a way that started them on a path that changed their lives. But these people were not particularly close to him. The people who tended to get hurt were the ones closest to him.

Tricycle: Gurdjieff used to say, “If you want to lose your religion, make friends with the priest.”

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: That is exactly applicable here. The only anger I ever really had toward Krishnamurti came out because of the way he turned on my mother when she took my father’s side in the lawsuits. He didn’t expect her to do that. And then he turned on her and said some very nasty things, none of which were true, yet they are being quoted now by some of his followers.

Tricycle: And that is when he turned on your father, too, isn’t it? And began lying about him to discredit him within the group?

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: Yes. He had his own problems, and I don’t judge him for that. But this act of deceit, that’s difficult to accept. And then, too, there are differences in attitudes toward telling lies in Asian and Christian cultures.

Tricycle: What effect did you expect this book would have on the Krishnamurti mystique in various countries among thousands and tousands of people all over the world?

Radha Rajagopal Sloss: I underestimated the impact. When I read the letters I have received, I had no idea how affected people would be by this material. The other biographics were so incomplete; I just felt that that was a poor way to leave history. It is simply not fair for such a false image to remain.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.